Current climate change has both human and natural causes.

Evaluating the wide range of scientific studies that relate to climate change is a monumental task. Here’s what everyone agrees on so far: Earth’s atmosphere is changing dramatically and with alarming speed. Analysis of CO2 trapped in ice cores reveals that current levels are higher than at any other time in the past 800,000 years, and the levels are rising at an increasing rate. In 2013, the average atmospheric concentration of CO2 was 396 ppm (parts per million); in May 2014 it topped 400 ppm. This is considerably higher than the preindustrial level of about 280 ppm—a level that had been maintained for millennia.

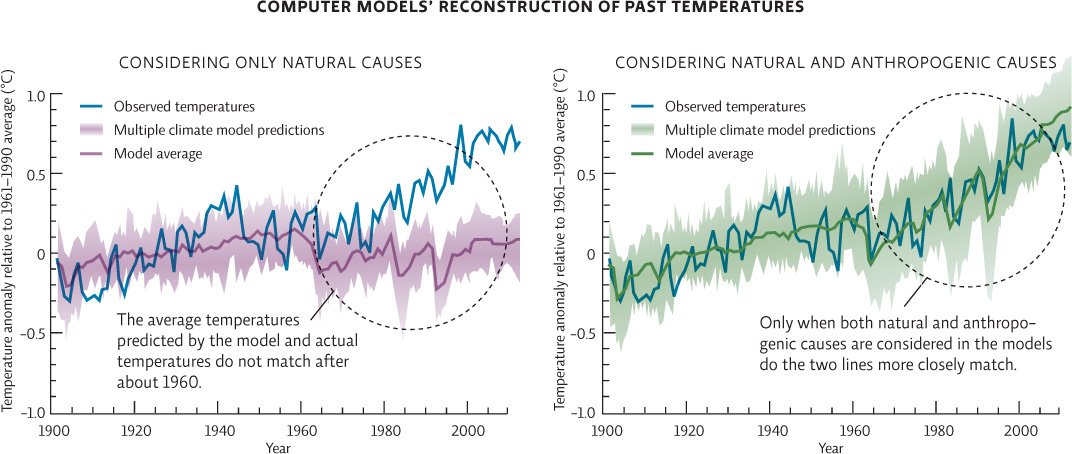

Based on all the clues they have gathered and analyzed, scientists agree that all the natural forcers combined are not enough to account for the rapid climate change that is currently under way. Only when we consider both natural and anthropogenic (related to human actions) forcers together do current trends make sense. In fact, the vast majority of this change is due to human activities, especially the burning of fossil fuels, and the consequent release of greenhouse gases like CO2 into the atmosphere. INFOGRAPHIC 21.8

Climate scientists use computer models (multiple mathematical equations) that take into account the major factors that are known to have affected past climates in order to see what might be responsible for recent warming. Data about natural and anthropogenic factors can be fed into a computer model separately and then together to see which circumstances match up with the warming that has been observed.

What would you expect the purple line and shaded area generated by the model in the left-hand graph in this infographic to look like, ‘ relative to the blue line (observed temperatures) if current warming could be explained by natural causes?

The blue line (observed temperatures) should be roughly centered within the purple shaded area and should be fairly close to the purple line itself (model average) - like it is in the right-hand graph.

anthropogenic

Caused by or related to human action.

For most of modern history, the United States has been the biggest emitter of CO2. In 2007, however, China took the lead: The proliferation of coal-fired power plants that has fueled the country’s recent economic and industrial growth has also released copious amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. China now releases nearly 30% more CO2 than the United States (though the United States has one of the highest per capita carbon footprints in the world, and much of the CO2 released in the 20th century came from U.S. sources).

Many climate scientists set the upper limit of CO2 that we should not cross (to avoid substantial negative effects, like the melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet and other events that we cannot reverse) at 450 ppm. At our current pace—featuring rapid fossil fuel consumption combined with sluggish efforts to curb our emissions—we will easily surpass that 450 ppm threshold before the end of the 21st century. But some scientists place the upper limit much lower, at 350 ppm—meaning we must not just reduce the amount of CO2 we release, we must bring down current atmospheric levels.

The reality is that we have already set into motion a chain of events that is dramatically changing the face of the planet: Glacial and permafrost melt, ocean acidification, and loss of carbon sinks and vital habitats due to deforestation are positive feedback cycles kicking CO2 accumulation into high gear, accelerating the pace of global warming.

KEY CONCEPT 21.9

Current warming cannot be explained without accounting for both natural and anthropogenic climate forcers.

But while the causes of climate change are scientifically well established, the future is still riddled with uncertainty. Forest ecologists like Frelich point out that one of the biggest uncertainties is the effect that changes in mean annual temperature and precipitation will have on the world’s forests. Some species may be able to migrate as temperatures rise and their optimum temperature range shifts northward—but which ones? Will spruce and fir species, which thrive in colder environments, disappear from the landscape? Will iconic and economically important trees like sugar maple and jack pine “move” to Canada? Will important ecological relationships be fractured as some species move or adapt while others (perhaps prey species or pollinators) do not?

Somewhere, buried in the reams of data that scientists like Frelich have spent decades accumulating, lie clues to answering these questions.