Climate change has environmental, economic, and health consequences.

The Boundary Waters Canoe Area surrounding Ham Lake—where Frelich and his colleagues were trapped—is the most heavily used chunk of the National Wilderness Preservation System. The boreal forest, its lakes, hiking trails, and breathtaking wildlife entice some 200,000 visitors every year, providing roughly 18,000 tourism jobs that pay a total of $240 million in wages. Global warming and shifting tree ranges threaten all that.

“Everyone’s worried about losing the forests,” Frelich said. “Resort owners, people who own cabins up there, local outfitters that rent camping gear—and the tourists themselves. If the forests burn too much, or if they descend into savanna, or can no longer support the iconic wildlife—like moose, lynx, and boreal owls—that people have come to expect, tourism will dry up. Because no one will want to vacation there.”

And it’s not just the tourism industry that will suffer in a warmer North Woods. The region as a whole supports about 1,000 forestry and logging jobs, which pay about $50 million in wages. On top of that, some individual species have become industries unto themselves—for example, the sugar maple.

Maple syrup production is heavily dependent on climate. The flow of sweet, sticky tree sap that eventually covers your pancakes is governed by changes in air pressure, which are in turn governed by changes in air temperature. When the temperature drops below freezing, the tree acts as a giant suction system, pulling the sap out of its branches, down into its roots. When the temperature rises above freezing, this action is reversed: The pressure gradient forces sap up from the roots, through the branches and out any holes—including ones that syrup makers have drilled for taps.

KEY CONCEPT 21.11

The effects of climate change are varied and are already being felt. Though there are some positive impacts, there will likely be more losers than winners.

Traditionally, climate in the northern United States— from Minnesota to Maine—has provided the optimal freeze—thaw patterns for this process, which syrup makers call “sugaring.” But in recent years, the transition from winter to spring has accelerated, leaving fewer freeze—thaw cycles and less sap overall. Meanwhile, across the border in Canada, warmer daytime temperatures have increased the number of freeze—thaw cycles, and some experts say that Canada is already in the middle of a syrup boom. “If current trends continue,” Woodall said, “it’s not impossible that the entire industry could one day be lost to Canada.”

For Woodall, the stakes are both more basic and more terrifying than the loss of any given industry: Societies that don’t protect their forests fail, he said. And it’s easy to see why. “Forests stabilize soil and clear water of pollutants,” he said. “In fact, the vast majority of Americans drink water that comes from a forested watershed. That means trees are as crucial to our survival as the water we drink.” The loss of forests is also another positive feedback loop that threatens to exacerbate climate change: Forests are an important carbon sink: They store trillions of tons of CO2 in their plants and soils. When they are burned, or die and decompose, much of that carbon is released into the atmosphere. (See LaunchPad Chapter 28 for more on the ecosystem services of forests.)

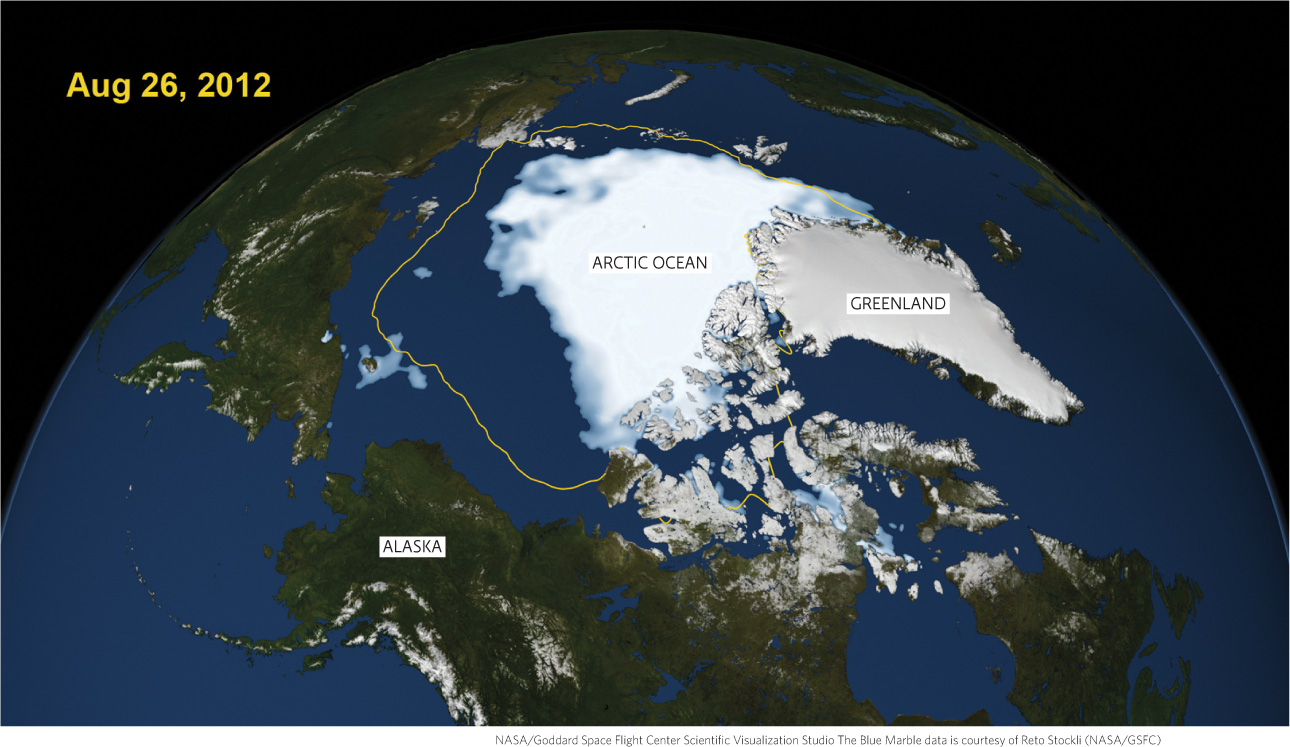

To be sure, some people and places will benefit from climate change. In Greenland, for example, warmer temperatures have enabled farmers to grow a wider variety of crops than they have been able to grow in the past. Warmer weather during the summer months has also opened the Northwest Passage in some recent years—a long-sought-after shipping route through the Arctic Ocean—which would significantly reduce the transport time for ships that otherwise have to take the southern route through the Panama Canal. High-latitude land in Canada and Siberia will likely become warmer and more habitable—lessening the incidences of cold-related health problems and deaths.

But other areas will suffer more harm than good, and many climate-related impacts are being felt now. Extreme weather has begun to claim both human lives and valuable crops. Coastal flooding is already affecting low-lying areas from Bangladesh to New Orleans. Wildfires are breaking records for size and destruction across arid regions of the United States, southern Europe, and Australia. On the whole, global crop productivity is decreasing, especially for maize, rice, and wheat. Though impacts such as crop declines, wildfires, and floods most certainly are affected by a number of factors, many have been linked directly to the changing climate.

Desertification and drought are accelerating in many regions where precipitation levels are declining, including the southern and Sahel regions of Africa, much of southern Asia, the Mediterranean region, and the western United States. At the same time, some regions, such as northern Scandinavia and parts of North America, are experiencing more precipitation, and much of that precipitation is coming in heavy rain and snow events. For example, the northeastern United States has experienced a 58% increase in the number of days with very heavy precipitation in the past 50 years. The type of precipitation matters as well; the Pacific Northwest is receiving more rain and less snow, which is resulting in less snowpack to feed rivers during spring thaws. This is already impacting local water supplies and salmon populations that depend on mountain streams for spawning runs.

With rising global temperatures, infectious tropical diseases have begun to migrate north of their traditional ranges. Dengue fever, for example, has made its way from regions with more tropical climates into Texas and Florida. A recent study by University of Michigan ecologists also showed that in warmer years, malaria spread (as predicted) out of lowland areas to higher latitudes in Ethiopia and Colombia.

Species worldwide are also being impacted by climate change. Though other factors contribute to species declines, in many cases climate change is a leading threat, often because it is occurring too rapidly for some populations to successfully adapt. The golden toad of Costa Rica’s cloud forest may have been the first species to go extinct due to climate change. Climate change has also been implicated in the decline or local extinction of many other species, such as various tropical coral species, Adélie penguins, the emblematic quiver tree of southern Africa, and the orange-spotted filefish, which has gone locally extinct in several coral reef communities in the Pacific Ocean. In fact, a 2004 evaluation made by a team led by University of York scientist Chris Thomas estimated that 15% to 37% of all species on Earth are “committed to extinction,” based on a midrange climate-warming scenario.