The impacts of nuclear accidents can be far reaching.

On March 16, members of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) determined that anyone more than 80 kilometers (50 miles) from the plant was probably safe from atmospheric radiation emitted by the disaster, based on computer models they had developed.

The finding did not quell public fears. In fact, long after the likely dispersal of radiation had been mapped and made widely known, people in many communities were fiercely divided about whether to evacuate. Local newspapers published daily radiation levels alongside weather reports, and average people sorted as best they could through reams of dense technical information—not all of it reliable—as they tried to make decisions about the health and safety of their families.

For months, it seemed, one new shocking discovery or scandalous revelation followed the next: The Japanese government discovered stores selling beef, spinach, and other food containing small amounts of radiation and scrambled to recall those products. Authorities warned parents not to give local milk to their children because children’s cells grow faster than those of adults, and that makes them more vulnerable to the effects of radiation.

Distrustful of government reports and frustrated by the lack of consistent information, average citizens began collecting and testing their own soil and water— sometimes getting disturbing results. On October 14, for example, the New York Times reported that citizen groups had found 20-odd spots in and around Tokyo that were contaminated with potentially dangerous levels of radioactive cesium.

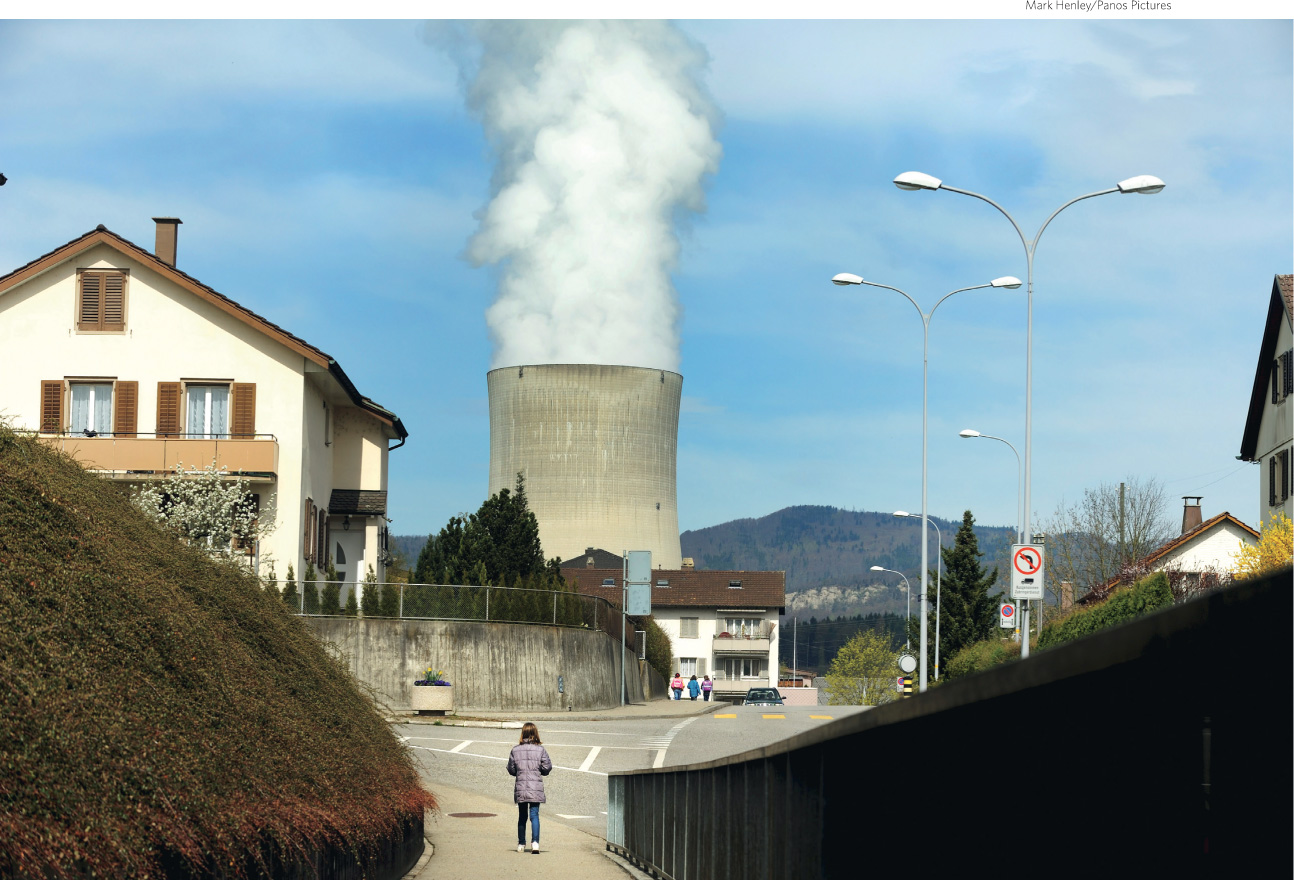

The impact on the natural environment has been more difficult to determine. “It depends so much on luck,” says Powers. “Even if everyone involved in the response does everything perfectly, we’re still at the mercy of the wind.” At first, the wind at Fukushima Daiichi blew steadily out to sea. But eventually it turned inland, to the northwest, carrying all those radioactive vapors with it. Rain and snow captured some particles, laying them deep in the mountains, forests, and streams around Fukushima. It will take decades before we know the full effect they will have on the ecosystems they have become a part of. But 5 months after the quake, Japan’s central government acknowledged that the area within 3 kilometers (1.8 miles) of the plant will likely be uninhabitable for decades.

Though radiation levels in surrounding areas are falling, parts of the reactor buildings were still not safe to enter some 3 years after the event. Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), the public utility that operated Fukushima, has been criticized for acting slowly and withholding information about local contamination and the clean-up operation. An estimated 300 million liters of radioactive water pumped out from the reactor buildings have been stored in hastily erected above-ground storage tanks. In 2014 a storage tank spill released 90,000 liters of highly radioactive water. The year before, more than 260,000 liters of radioactive water leaked out of the reactors and reached the Pacific Ocean. The construction of an “ice wall” began in 2014 in an attempt to prevent more groundwater from seeping into the plant and becoming contaminated. Pipes containing super cooling fluid are being sunk into the ground to freeze the groundwater around the entire complex.

Will there be any long-term effects on residents and workers as a result of the accident? A 2014 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimates only a very slight increase in the lifetime risk of cancer for people living in Fukushima Prefecture at the time of the disaster, a level that the authors say is “unlikely to be epidemiologically detectable.” This may be good news, but as of February 2014, some 136,000 evacuees still cannot (or will not) return home. Residents are being allowed to reoccupy some areas (areas with acceptable levels of radiation); other areas with slightly higher radiation levels have been opened for day visits (to clean, rebuild, and restore). Remediation of the areas continues, with the hope of allowing more residents to return. Still, officials expect at least half of the area within 20 kilometers (12.5 miles) of the nuclear power plant to remain closed for the foreseeable future.