Counteracting overgrazing requires careful planning.

One of these ranchers was Jim Howell. Howell had grown up on his family’s ranch in Colorado and was studying to be a veterinarian when he came across Savory’s work in the mid-1990s. “I saw quickly that the way my family had managed the land, going back to when they first bought it in 1937, was hurting it,” he says. “We were losing biodiversity, losing soil, and every year the land was yielding up less profits than it had the year before.” Convinced that being a good rancher meant being a good ecologist, Howell switched majors, became an ecologist, and promptly began looking for opportunities to put Savory’s methods to the test.

Eventually, he partnered with a group of investors to create Grasslands, LLC, a private equity fund whose aim is to buy up failing ranches throughout the Great Plains region and use Savory’s holistic management techniques to resuscitate them. In 2010, the group made its first purchase: Horse Creek and a neighboring ranch that together hold 60 square kilometers (23 square miles) of degraded South Dakota rangeland—roughly equal in size to the island of Manhattan.

With careful planning, Howell’s ranching team can work around several seasonal constrictions at once, including water availability, the bloom cycles of poisonous plants, and the migration patterns of various wild animals. Not returning to the same small paddock for a full year also breaks the reproductive cycle of many parasites. And keeping animals tightly bunched for a set period of time ensures that all plants are grazed equally—not just the sweetest grasses, but the weeds, too. This actually gives the better-tasting plants an advantage: Because they don’t waste as much energy on chemical defenses (which is what makes some plants so unpalatable in the first place), they regrow faster and thus colonize more area than the foul-tasting plants.

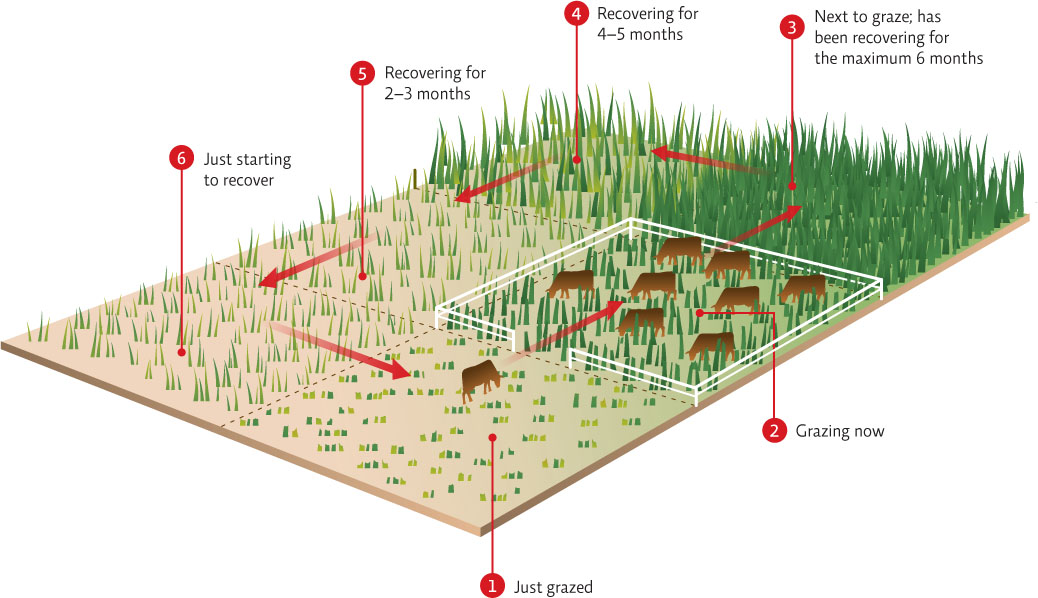

On top of that, planned grazing helps keep plant biomass levels within an ideal range, where plants capture a maximum amount of sunlight and thus grow exceedingly quickly. Below this range, plants have less leaf area, capture less solar energy, and grow much more slowly as a result; above it, excessive leaf growth blocks newer shoots from the Sun, and old leaves die as fast as new ones are made. Grasses kept between these two extremes regenerate much more quickly and are thus ideal for grazing. INFOGRAPHIC 27.7

Livestock are allowed to graze intensively on a plot and then are moved to the next plot. In this example, each plot is grazed for 1 month. By the time the livestock return to a given plot, it will have recovered.

What could be the result if a rancher practicing planned grazing moved cattle out of a paddock too soon? Too late?

The grasses must be monitored for growth to determine the ideal time to move cattle out of one paddock into the next. If the cattle are moved too soon, the rancher does not tap the full potential of that pasture to help the livestock grow and may allow the cattle to leave behind some unpalatable weeds that would then have an advantage in regrowth over the more fully cropped sweet-tasting grasses. If the cattle are moved too late, they might damage the grasses, making it harder for the grasses to recover.

Howell says the end result of such careful planning is that land productivity is maximized and ranching becomes profitable once again. So far, the numbers support his claim. In one U.S.-based study, early adopters of planned grazing averaged 300% profit increases in the first 5 years. “You’re raising twice as many animals in the same amount of space,” explains Howell. “It’s like getting a second ranch for free.”

In fact, the financial benefits have proven so substantial, Howell and his partners are betting that the economy will rebound in tandem with the land. “Ultimately, we want to sell these places back to the surrounding communities,” says Howell. “At the very least, we hope to inject some energy into the region—provide jobs, attract young people.”

But planned grazing is tricky work, especially for ranchers who are set in their ways and are already anxious about the bottom line. “It’s very hard to make a ranch profitable in the first place. So significant change can be very frightening,” says Howell. In more traditional grazing methods, animals are left in the same pasture for long periods, sometimes for an entire growing season, which can run for as long as 180 days. With holistic planned grazing—as Savory’s method is called—animals are moved much more frequently. “It’s really easy to screw things up when you switch from regular grazing to planned grazing,” says Howell. “It’s easy enough if you have 3 pastures and a 180-day growing season—each pasture gets about 60 days of grazing and 120 days of recovery,” Howell says. “But say you have 45 pastures. That’d give you an average grazing period of only 4 days. If you’re off by even a day, your animals can suffer considerably.” Leave them on a given pasture too long, and they will run out of food. Do that too often, and the animals’ ability to gain weight, lactate, come into heat, and reproduce will all be compromised. And that can take a huge economic toll.

Not everyone agrees that the risk is worth it. Most ranchers acknowledge that sustainable grazing—grazing that maintains the health of the ecosystem and allows the grasses to recover before the animals return—is essential to protecting grasslands the world over. But some argue that existing methods of continuous grazing work just as well, if not better, when done properly. “There is plenty of evidence showing comparable outcomes for biodiversity, soil erosion, etc.,” says David Briske, a rangeland ecologist at Texas A&M University. In 2013, Savory presented his ideas to the general public in a TED talk. Briske and colleagues offered a detailed rebuttal to some of Savory’s TED talk claims in an article published in the journal Rangelands.

sustainable grazing

Practices that allow animals to graze in a way that keeps pastures healthy and allows grasses to recover.

In contrast, a review article by Teague (also at Texas A&M University) and colleagues offers a scientific critique in favor of Savory’s method, stressing that only studies done at the large spatial scale of most ranches (rather than the smaller-scale studies that are typical of most experimental studies) generate usable data about the impact of various grazing techniques. These large-scale experimental studies, along with numerous case studies of holistic planned grazing in action on ranches around the world, they argue, validate planned grazing. Briske, in the 2011 article, acknowledged that holistic planned grazing has certainly been shown to work on ranches around the world but points out that these anecdotal successes do not rule out the possibility that the improvement in these degraded rangelands might have come from better management in general rather than this particular method. These articles by Briske and Teague are examples of science and information literacy in action—questioning claims by evaluating the evidence used to make those claims and offering evidence in support of alternate conclusions.

Though they disagree on some points, Briske and Teague agree that the identification of the “best method” for grazing may be the wrong goal, considering the complexities of grasslands—which are subject to the vagaries of weather, fire, and grazing livestock. The question of how best to graze livestock gets more complex when relevant social factors such as ranchers’ management preferences and economic goals and resources are factored in. “Effective management of grazed ecosystems is sufficiently dynamic and complex that it should not be envisioned to have any one correct solution,” writes Briske.

Though Briske disagrees with Howell and Teague about the superiority of planned grazing, they all agree that adaptive management of rangelands is key. Holistic planned grazing, or the simpler rotational grazing that moves animals less frequently, takes work and attention to detail and a willingness to move animals sooner or later than anticipated, based on how well the plants are growing. As Howell points out, planned grazing is not easy, but if done properly, he believes it can allow ranchers to graze livestock and maintain or even restore rangelands.