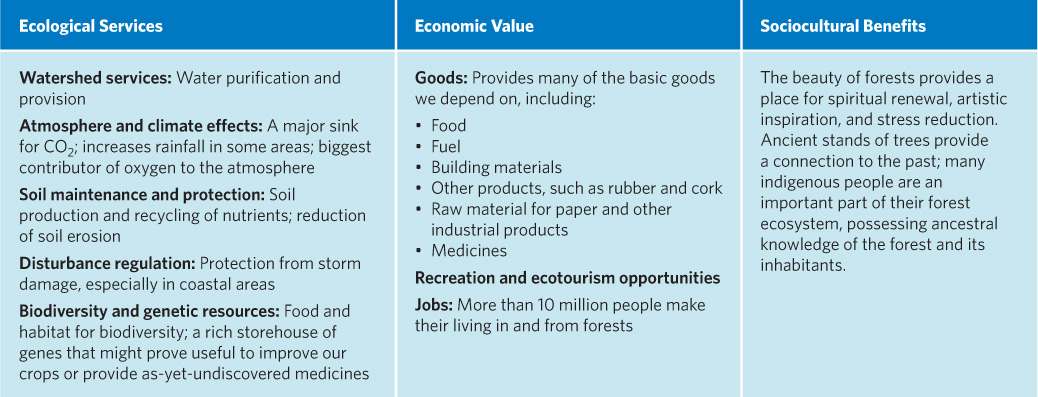

Forests provide a range of goods and services.

Though trees are the largest and most notable life-forms present, a forest is much more than just its trees. Together, the species inhabiting the different layers participate in a delicate symphony of chemical and physical cycles that produce an invaluable range of ecosystem services for the planet.

It starts with the soil, which the forest itself helps to form and maintain: Leaves and branches die, fall to the ground, and decay, forming a thick brown layer of nutrients in which all future generations of plant life will take root.

While dead and decaying plants help form the soil, living ones hold it in place. During rain storms, roots—especially tree roots—anchor soil in place so that it can’t flow as easily down hillsides into nearby surface waters (lakes, streams, oceans) with the rain. Soil and roots also slow the flow of rainwater across the ground’s surface (called runoff), preventing potentially polluted water from reaching surface waters. And, by slowing runoff, a well-vegetated area allows more water to soak into the ground, recharging the groundwater supplies that provide area residents with their major source of drinking water. The soil also traps chemicals that might otherwise contaminate that drinking water. (See Chapter 15 for more on runoff.)

runoff

Water that flows across the land surface under the force of gravity, usually after a rainfall.

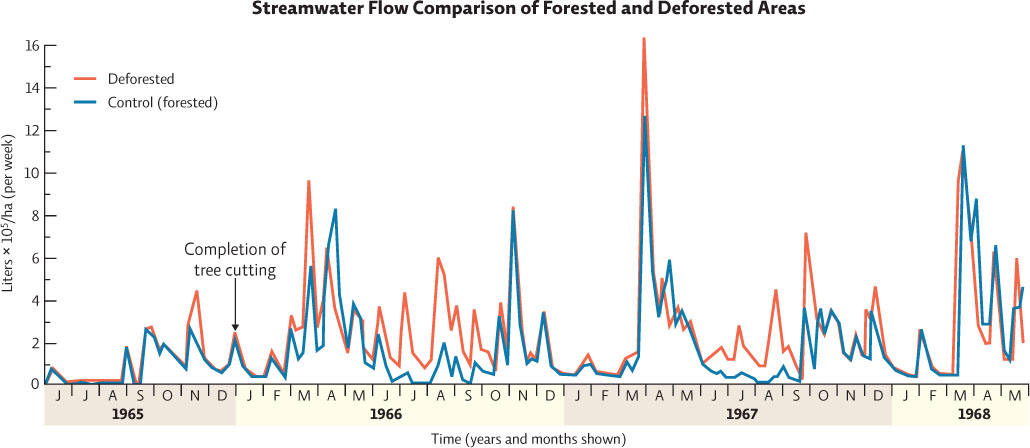

The value of intact forests in reducing runoff was demonstrated in classic research at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire, a unique experimental area that has allowed scientists to conduct well-controlled, ecosystem-level experiments in the field. This research center in the White Mountains of New Hampshire consists of several valleys and streams that can be manipulated as test and control plots for experimental purposes. Small dams allow researchers to carefully monitor the volume of water that flows through the forest as well as the chemical composition of the water. In one of the first studies there, conducted in the late 1960s, researchers compared the volume of stream water flow from streams in similar valleys that were either left forested or that were completely deforested. Stream flow in the deforested areas was 30% to 40% higher than in forested areas, indicating that these areas received significantly more runoff from the deforested land area than did streams that were surrounded by intact forest.

KEY CONCEPT 28.3

Forests provide important ecological, economic, and sociocultural services.

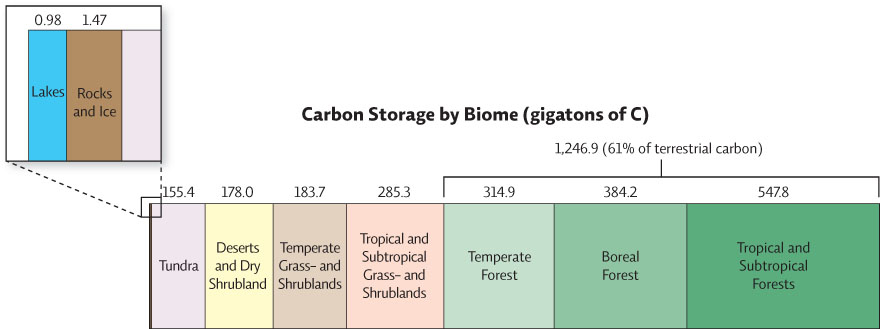

While plants, soil, and water are playing off one another in this manner, the forest is also conducting another important cycle: pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and replacing it with oxygen (through the process of photosynthesis). In fact, forests as a whole store more carbon in their biomass, litter, and soil than all the carbon in the atmosphere, making this biome the world’s largest terrestrial carbon sink—an area that stores more carbon than it releases, such as the standing timber in a forest or organic matter in soil. (The oceans hold more carbon, but their capacity to absorb more may be diminishing.) And forest leaves produce so much oxygen that they are commonly referred to as “the lungs of the planet.” INFOGRAPHIC 28.3

carbon sink

An area such as a forest, ocean sediment, or soil, where accumulated carbon does not readily reenter the carbon cycle.

Forests provide many ecological services, including protecting surface waters from runoff pollution. A study conducted in the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest showed that streams in deforested areas had much higher stream flows than nearby forested areas due to higher levels of runoff reaching the streams after a rainfall.

The terrestrial biomes of the world store almost three times as much carbon in above-ground biomass and soil as is found in the atmosphere, making them vital carbon sinks. Forests hold the most by far. Most of the carbon in tropical forests is in above-ground biomass, whereas in boreal forests, the majority is in the soil and leaf litter, where cold year-round temperatures retard decomposition. Maintaining forest integrity is crucial to retain this carbon-storage ecosystem service.

Researchers could have also done this study by measuring runoff for a few years in a single stream, then clear-cutting the forest around that stream and measuring runoff for another few years. What is the drawback to this method compared to the way the study was actually done?

Because rainfall differs from year to year, a direct comparison of 2 streams in neighboring valleys allows a more accurate comparison of runoff during each rain event.

Last but not least, virtually every layer of forest provides food and habitat for a bevy of animals (vertebrates and invertebrates), fungi, and microbes; these creatures all do their part to contribute to the functioning of the forest ecosystem as a whole. It is difficult to overstate the importance of forests to the biosphere.

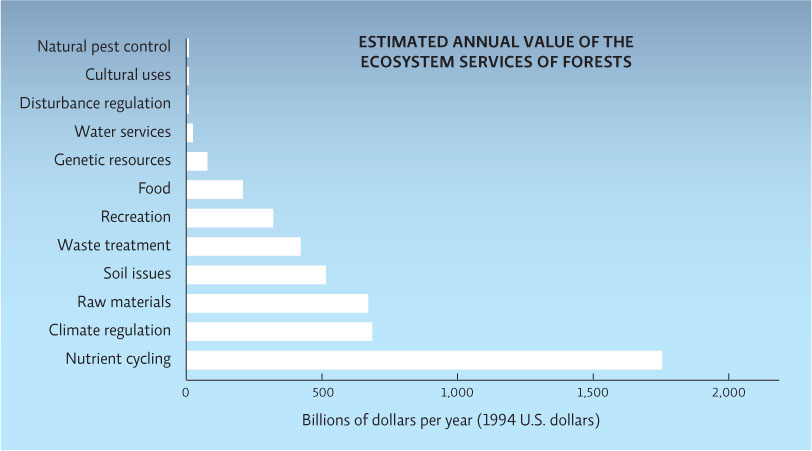

In addition to all these ecosystem services, forests also provide a range of economic benefits. In fact, humans have relied on forests for millennia for a multitude of consumer goods. Wood products, including lumber, firewood, charcoal, paper pulp, and some medicines, account for some $100 billion in global trade every year. On top of that, the wildlife supported by forests provides humans with food and recreational hunting opportunities, both of which have economic value. TABLE 28.1, INFOGRAPHIC 28.4

All ecosystems, including forests, contribute to the ongoing functioning of the planet and the immediate well-being of humans. Some of these services we take for granted; others are recognized for their economic value. One calculation estimates the value of services provided for free by ecosystems of the world at trillions of dollars per year, a value greater than the GNP of all nations of the world combined.

Explain how the sustainable harvesting of forest products, which would provide less annual income than harvesting the trees themselves for timber, can be more economically valuable than the wholesale removal of the valuable timber in that forest.

Though the value of the trees may be higher in the short-term, once you have harvested them, you no longer have a forest and must wait a long time for it to grow back. So keeping the forest intact and sustainably harvesting its products can provide income, year after year and eventually exceed the value of the trees themselves.

Robert Costanza and his colleagues evaluated ecosystem services of forests and quantified their value (in 1994 U.S. dollars) to be $4.7 trillion.

Compare the ecosystem services of forests shown in this graph to the graph shown in Infographic 6.1 of ecosystem services in general (all biomes).

A comparison of the two graphs shows that while nutrient cycling is the most important in forests and overall, forests play a major role, compared to other biomes, in climate regulation and as a source of raw materials.

In Haiti, the cost of deforestation spun out over decades and proved catastrophic. Soil eroded down into streams, rivers, and gullies, clogging them with sediment and disrupting aquatic ecosystems. With nothing to absorb the water, floods became more severe, and groundwater sources were quickly depleted as the water flowed away rather than soaking into the ground. Slowly, crop yields shrank. As the forest habitat was fragmented, biodiversity dwindled. And as the trees vanished, the people of Haiti suffered. Unlike wealthier countries, Haiti could not afford expensive water purification systems—a service the forests once provided for free. “It took some years before we could feel the other effects of deforestation,” says Georges. “The floods got worse, and we lost drinking water to runoff and pollution. And once those problems started, there was no easy way to fix them.”

Eventually, everyone who could abandoned the countryside for the capital city. Even that did not stop the tide of deforestation. As the population swelled, so did the demand for fuel, which in Haiti still comes almost exclusively from trees.