Forests can be managed to protect or enhance their ecological and economic productivity.

Funding and technical expertise can facilitate more effective forest management in developed nations. For example, in 1905, the United States established the National Forest Service. Its first director, Gifford Pinchot, challenged the prevailing notion that U.S. forests were inexhaustible and introduced the idea of sustainable forestry—taking only what the forests could sustainably produce or replace. The focus in those early years was maximum sustainable yield (MSY): harvesting as much as sustainably possible (but no more) for the greatest economic benefit. In 1960, the United States expanded on Pinchot’s ideas and enacted the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act, which mandated that national forests be managed in a way that balances a variety of uses—outdoor recreation and timber interests as well as the health of watersheds, fish, and wildlife. No single use could predominate.

maximum sustainable yield (MSY)

Harvesting as much as is sustainably possible (but no more) for the greatest economic benefit.

Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act

U.S. legislation (1960) mandating that national forests be managed in a way that balances a variety of uses.

KEY CONCEPT 28.5

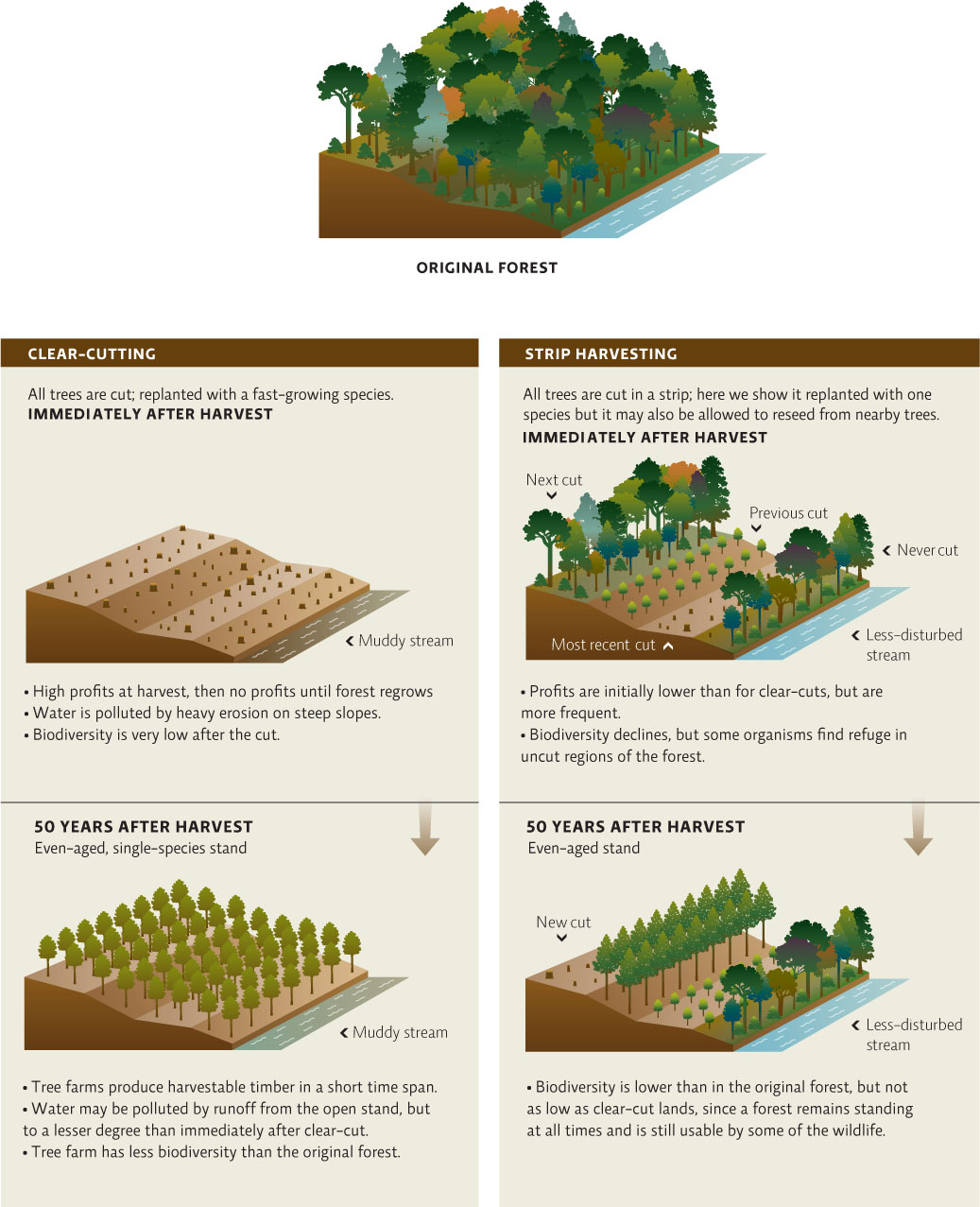

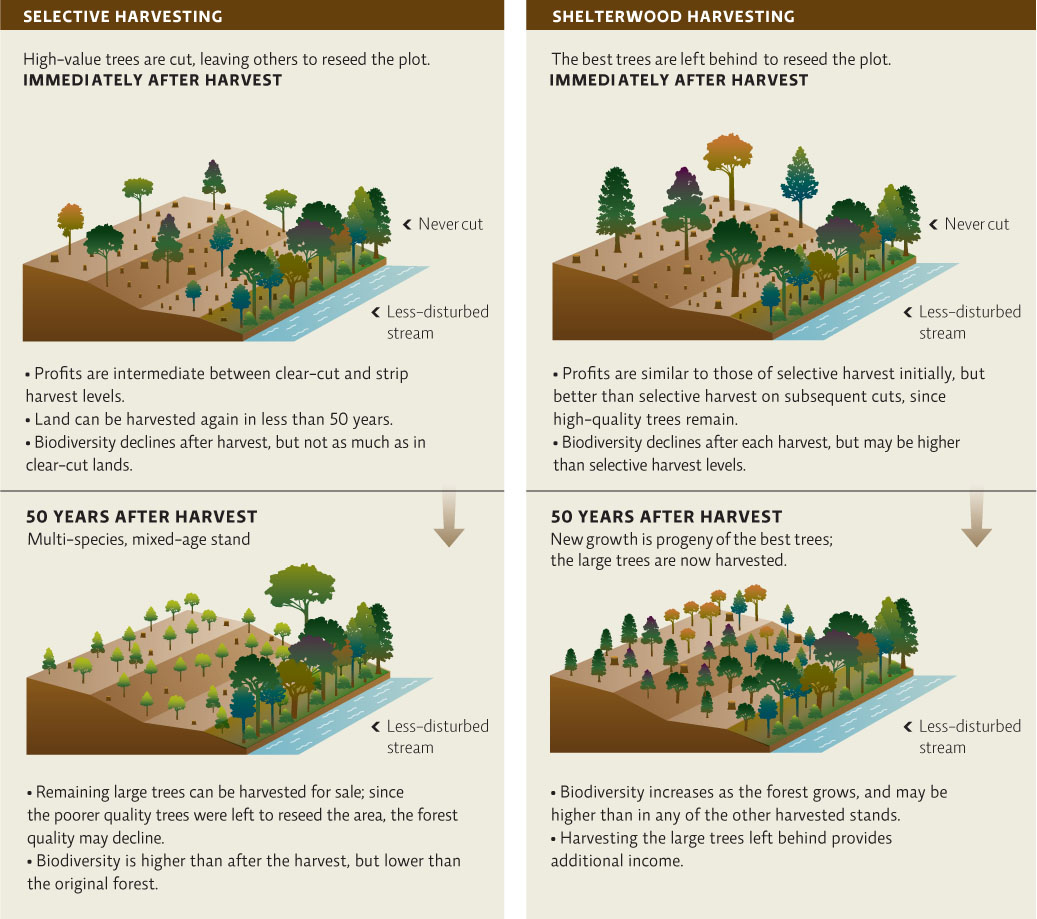

Selective and shelterwood timber harvesting maximize long-term profits and protect biodiversity; clear-cutting methods maximize short-term profits at the expense of the local ecosystem. Tree farms are a highly productive alternative that may allow managers to leave natural stands alone.

Today the U.S. National Forest Service, administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, oversees 155 national forests (and 20 national grasslands) and provides guidance for the management of private forests and grasslands, both nationally and internationally. Its overriding objective is the management of these areas in an ecologically sustainable manner, and it promotes forest ecosystem management (FEM) as the best way to meet this mandate. Rather than focus exclusively on timber harvests and maximum sustainable yields, FEM aims to manage the forest ecosystem as a whole. This includes a variety of techniques for timber harvesting, vegetation removal, and controlled burns to remove deadwood and stimulate seed germination in fire-adapted species, as well as restoration of forested areas and research in forestry (ecology and economic uses).

forest ecosystem management (FEM)

A system that focuses on managing the forest as a whole rather than for maximizing yields of a specific product.

Though some timber harvesting methods are very damaging to the integrity of the forest (such as large clear-cuts on steep slopes), some methods reduce disruption to the ecosystem while still providing economically valuable forest products. Ideally, the stand of trees—its health, age, and species composition—and the slope of the land determine the harvesting method. Consideration is also given to the other species that reside there. When trees are harvested properly, they can provide immediate and long-term economic benefits without serious environmental damage. Even clear-cutting can be appropriate when it increases the overall health and viability of a future forest by removing unhealthy or genetically inferior trees and replacing them with better stock. Clear-cuts followed by planting of a fast-growing, high-value tree (a tree farm) can also reduce the pressure to cut other forests. (However, there must be enough native forests left in areas suitable for tree farms to avoid serious ecological damage due to biodiversity loss.) INFOGRAPHIC 28.6

There are many ways to harvest trees from a forest, each with its own economic and ecological trade-offs. Here are variations of four techniques. To evaluate the impact of a particular method, consider what the area would look like 50 years after a harvest.

Clear-cutting radically changes the ecosystem and can cause serious ecological damage. When then, might it be ecologically sound to clear-cut, and what restrictions would you place on such an action?

If the stand of trees is diseased or contains a large number of invasive species, the area might benefit from a clear-cut. Likewise, if you are trying to manage the area for a species that requires some open space, then a small clear-cut (or several here and there within its range) might benefit that species. The main restrictions to consider would be to keep the area cut small (not the entire forest) and to avoid clear-cutting on steep slopes or next to a stream (to prevent soil erosion).

Forest management is not without its critics, however. Conflicting interests make it difficult to achieve a balance between multiple forest uses and ecosystem protection. For example, harvesting trees in the Pacific Northwest provides many jobs, good profits for timber companies, and useful products for homes and businesses, but it can reduce biodiversity and harm salmon runs, which are vital for ecosystem health, native cultures, and the tourism industry.

Debates are often oversimplified and shown as two competing options—owls versus jobs—however, a more accurate cost-accounting of potential forest uses requires that we factor in the economic and ecological values of ecosystem services. Forests are so important economically, ecologically, recreationally, and even spiritually that no matter how well managed they are, they will always be a contentious resource.

Three months after the kombit visited his hillside farm, Jean Robert is harvesting moringa leaves. They’re tasty and packed with protein, and when harvested properly, they regrow rather quickly. If everything goes as expected, he will eventually have a bevy of crops to see him through the year: mangoes in the summertime, coffee in the fall, and, if he’s lucky, oak and mahogany stands that will yield high prices in the timber market down the road. In the meantime, the moringa trees provide his family with a sustainable supply of protein and fuel wood.

The trees Georges’ team plants can be broken down into three main types. They start with fast-growing, multipurpose trees like the moringa. Because it is a nitrogen-fixing plant, the moringa helps refertilize the soil. And because it grows quickly, it can provide a sustainable source of food and fuel wood. Next, they plant fruit trees—mangoes, avocados, and citrus. These trees take longer—3 to 5 years—before they are ready to harvest, but they put down roots and thus stabilize the soil in just a few months’ time. “Farmers are less likely to cut down fruit trees for charcoal, because they know it will provide the kind of food they can both eat and sell for profit,” says Georges. “Fruit trees are worth something alive.” The last thing the kombit plants is the slow-growing timber trees, which may be sustainably and profitably harvested in the future but don’t provide any immediate benefits to the farmers. “The goal is to mix it up,” says Georges. “You can create a whole stable system that’s going to provide money and food throughout the seasons and across the years.”

Of course, for any of this to work, urban-dwelling Haitians need a new, sustainable energy source.