The way we raise livestock may jeopardize the safety of food products.

E. coli O157:H7, or just 157, as it is called by public health experts, tends to reside in the colon of some farm animals, especially cattle. The cattle themselves are immune to the bacterium and normally pass it in their feces without incident. But sometimes the 157-laden feces gets on the animal itself, and sometimes it stays there, even as the animal is slaughtered and made into steak and hamburger that we then eat.

In humans, 157 can cause bloody diarrhea, dehydration, and even kidney failure. The sickness usually clears up within a week in adults. But it can be deadly in people with compromised or underdeveloped immune systems, including infants, young children, and the elderly. In all, 3%–5% of cases prove fatal.

That potential for fatality meant health officials were in a race against the clock. The New York State Health Department notified Topps, the company that had processed the meat, which then recalled some 150,600 kilograms (332,000 pounds) of beef from supermarket shelves, restaurant kitchens, and freezers across the country. On September 30, that recall expanded to include 9.8 million kilograms (21.7 million pounds) of beef—enough to make one hamburger for every single U.S. resident.

As supermarket and restaurant owners across the country began pulling the company’s products from their freezer shelves, health officials began the tedious work of tracing the tainted beef back to its origins—trying to discern, from company documents and good detective work, which of dozens of suppliers the offending cattle had come from.

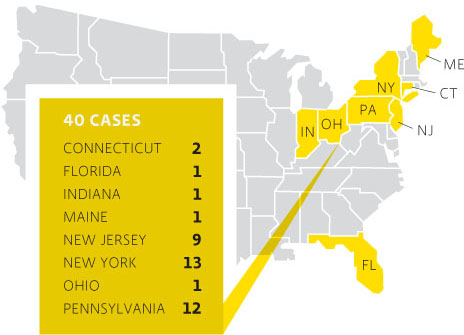

Of course, by then, most of the suspect meat had already been consumed. The final tally: 40 people sick, across eight states, 21 of them hospitalized. “The real numbers were probably larger than that,” says Paul Ebner, a professor of animal sciences at Purdue University, “because not every case would be confirmed through proper diagnostics.”

Still, those confirmed cases were enough to put Topps, one of the country’s largest meat-processing plants, out of business. On October 4, a class-action suit was filed against the company. On October 5, embattled by negative publicity and faced with hundreds of millions of dollars in lost profit, the processing plant closed down.

The beef recall of 2007 made national headlines, but beneath those headlines were debates that had already been raging for years and continue to this day. Some cattle farmers and beef industry representatives insist that despite a few isolated incidents, our food supply is safer than it’s ever been. Meat is part of a healthy diet, they argue, and industrial-scale production—done in operations known as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs)—allows meat suppliers to raise more beef with fewer animals (more meat per animal); those high-density operations more efficiently rear livestock because they require less grazing land per animal than traditional methods.

concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO)

A situation in which meat or dairy animals are raised in confined spaces, maximizing the number of animals that can be reared in a small area.

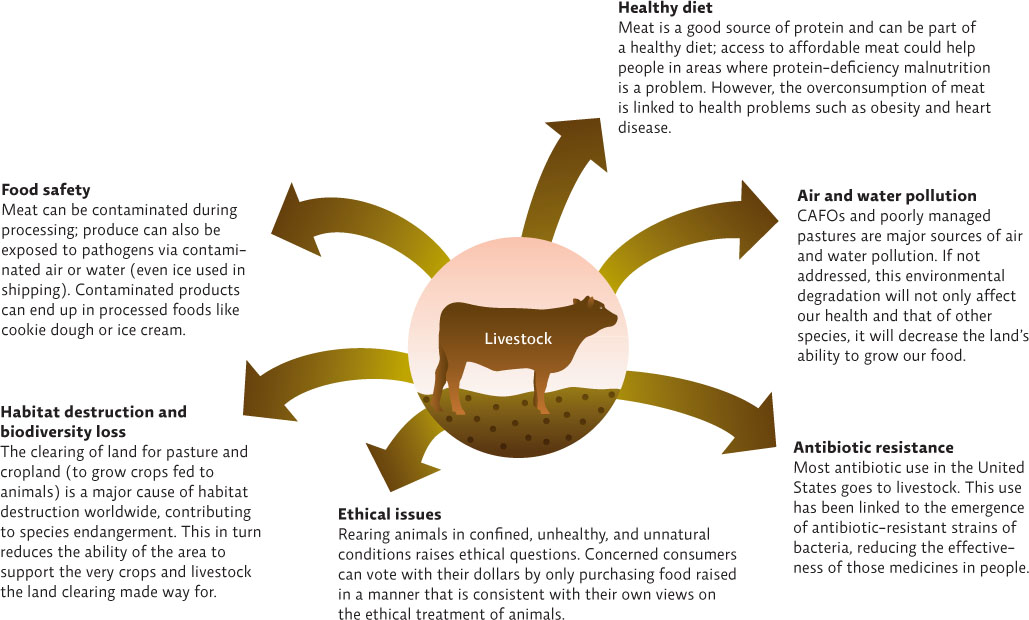

Critics, on the other hand, contend that the entire system through which we grow, process, distribute, and consume food is wildly incompatible with human health and environmental sustainability. And food safety issues are just the tip of the iceberg. Our overconsumption of meat has contributed to a vast array of social ills, they say—not only epidemics of obesity and heart disease but also air and water pollution in regions surrounding crowded animal farms and biodiversity loss and greenhouse gas emissions around the globe. INFOGRAPHIC 30.1

Food safety and health issues are real but are not the only problems associated with the rearing and slaughtering of livestock for food. The industrial method of raising large numbers of animals in crowded conditions has tremendous environmental impacts and raises ethical questions about the way the animals are treated.

Although hamburgers are more often associated with sickness related to E. coli contamination than steak is, fecal matter can also contaminate the surface of a steak. Cooking the steak (even to rare temperature) will likely kill the bacteria, but if that same steak is ground up, the E. coli is evenly distributed throughout the meat and if the burger is not cooked completely, the consumer can become infected. This is why the U.S. Department of Agriculture recommends that all ground meat be cooked to an internal temperature of 71°C (160°F).

Which of these issues arising from industrial animal rearing—ecological, ethical, or health—concerns you the most ? Explain.

Answers will vary but should be supported. Ecological reasons might be a concern because they impact the ability of ecosystems to function well and provide important ecosystem services (including the support of agriculture). These ecological concerns also impact human health directly in terms of air and water pollution and antibiotic resistance. The health concerns of not getting enough protein in one's diet is especially concerning for those of lower incomes so one could argue that to reduce industrial production of meat would hurt those individuals; on the other hand, the obesity epidemic and cardiovascular disease in the U.S. and other places is on the rise and is correlated with diets higher in meat. These health problems extract an enormous toll on people and communities worldwide. An argument that ethical issues are the biggest concern would raise the bigger questions of why we do what we do and how our beliefs should influence our choices - especially at the societal level.

KEY CONCEPT 30.1

The industrial methods used to rear animals raise environmental, health, and ethical concerns.

At the heart of the issue are fundamental questions whose answers will impact not only the health of our citizens but also the state of the planet we live on.