Affluence influences diet.

The past few decades have seen an unprecedented rise in global affluence. In Africa, a continent still plagued by war, famine, and poverty, consumption of resources has doubled since the start of the 20th century; in developed nations, like the United States, affluence has increased sixfold. As we learned in previous chapters, greater affluence means a greater ecological footprint. Put another way: People with more money consume more resources—not just more material goods but also more food.

affluence

The state of having great wealth.

KEY CONCEPT 30.2

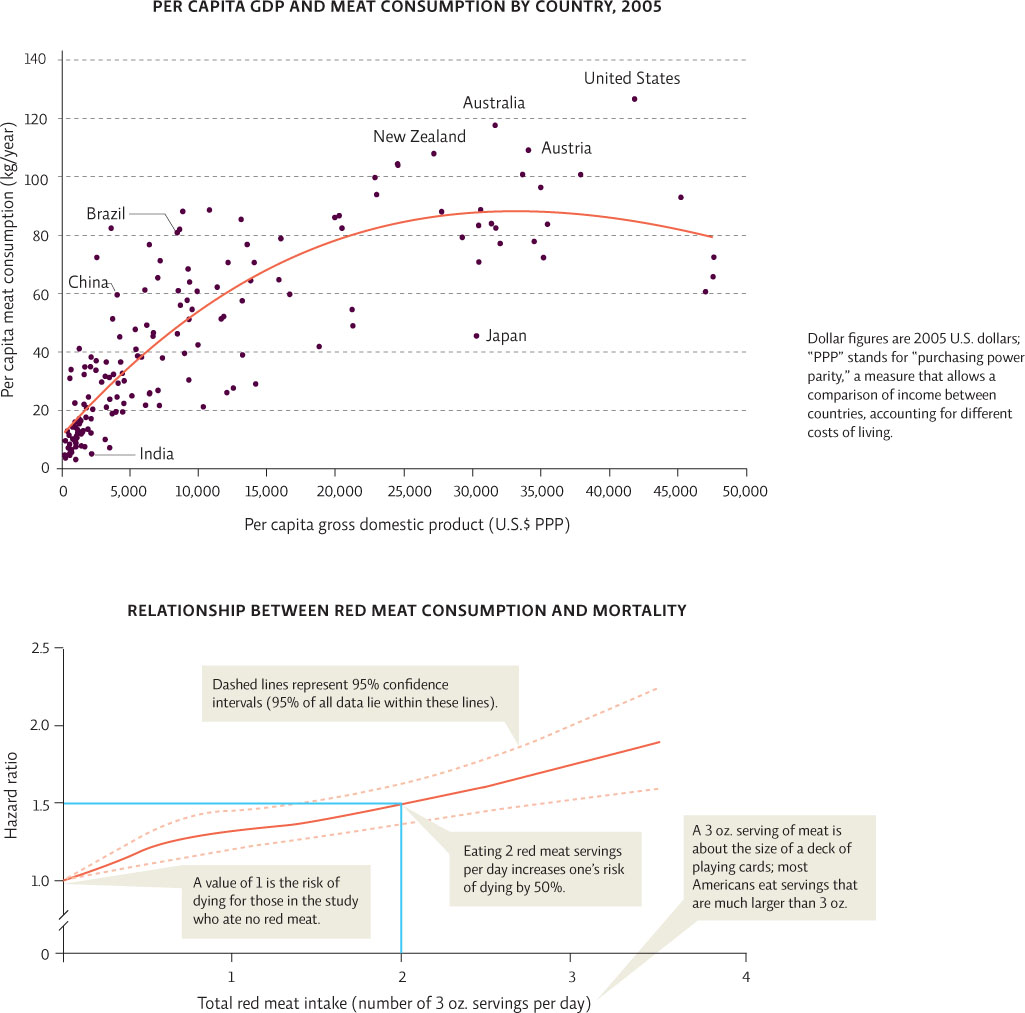

As income increases, so does the consumption of meat; this can boost protein consumption in people who are malnourished but can lead to health problems if overconsumed.

Of course, wealthier people don’t just eat more food. They eat more of a certain kind of food—specifically, more animal products, like meat and eggs. This is not entirely a bad thing. In developing nations especially, meat and dairy products mean more and better sources of protein. But while meat and dairy production has increased in both developing and developed nations in recent years, per capita consumption is still much higher in developed nations (as much as three or four times higher, by some estimates). In fact, most health experts agree that while meat can be part of a healthy diet, Americans especially are eating too much of it—on average, 125 kilograms (275 pounds) per person per year. That overconsumption has been associated in many studies with a wide range of health problems—from cardiovascular disease and diabetes to gout and some cancers. Researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health have found that as red meat consumption increases, so does a person’s risk of dying. Replacing some red meat with fish, poultry, or non-meat sources of protein decreases risk by 7%–19%.

It isn’t just the overconsumption of meat that is problematic—it’s overconsumption in general. A diet high in calories, fat, and sugar, coupled with declines in physical activity, is increasing rates of obesity worldwide. For a recent example of how much affluence influences meat consumption, one need only look to China. In tandem with its economic growth, the country’s annual per capita meat consumption tripled between 1985 and 2005, going from 20 kilograms (44 pounds) per person per year to 60 kilo-grams (132 pounds) per person per year. INFOGRAPHIC 30.2

Worldwide, as income rises, so does the consumption of meat. Eating meat and other animal proteins can improve the health of those who are protein deficient, but a diet high in fat and calories is linked to serious health problems. Though meat is not the only dietary factor linked to these health problems, eating large amounts of meat is believed to be a contributing factor.

Many studies show strong links between red meat consumption and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. An Pan and colleagues from the Harvard School of Public Health evaluated the link between red meat (beef, pork, and lamb) in the diet and mortality (death) in participants enrolled in a long-term (22-year) study that followed the health and diet of more than 50,000 men. Results were adjusted for other variables that affect mortality, such as age, smoking, physical activity, body size, family history of disease, and other dietary choices. The data show that as daily red meat consumption goes up, so does one's risk of death. Comparable results were obtained from a similar study which followed more than 100,000 women from 1980 to 2008.

Estimate (or measure) the number of 3 oz servings of red meat you eat in a week and then convert that to a daily average. What hazard risk does this give you based on the central line on the RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN RED MEAT CONSUMPTION AND MORTALITY graph? Based on this information, would you consider changing the amount of red meat you eat? Explain.

Answers will vary. Those who eat 1 or fewer servings a day, may not see the need to change whereas those who eat several may. Whether an increased hazard risk influences one’s willingness to change might be affected by food preference, willingness to take the risk, acknowledgment that other, more serious risks exist, etc. Whatever the conclusion, it should be supported.

To accommodate such growing appetites, we have dramatically altered the way we rear livestock. Instead of using traditional mixed farms, where crops and livestock are rotated, or grown side by side, we now rear animals in CAFOs, factory-like operations where livestock are densely packed and rapidly grown. Since about the mid-1900s, high-density operations have been the most common method of raising cattle in the United States. Today, poultry (chicken and ducks) and pigs are also predominantly raised in CAFOs. And the practice is spreading to other countries.

So far, CAFOs have enabled us to grow many thousands more food animals than Mother Nature would ever allow. CAFO managers say that’s a good thing. Such dramatic increases in production have not only brought more meat to people of rising affluence but have also made it cheaper and thus more accessible to all people, even those whose income is not rising. But critics say that that is the very crux of the problem. CAFOs are the foundation of the cheap fast food that too many low-income Americans depend on, says Doug Gurian-Sherman, a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nonprofit group that lobbies for environmentally responsible food policies. It’s these kinds of operations that make fast food hamburgers cheaper than fruits and vegetables. And that economic reality has brought with it serious consequences, not only for human health but also for environmental safety and animal rights.