U.S. food policies support industrial agriculture.

To understand our modern food system, we must go back to the 1930s and the Great Depression. It was then that legislators created the U.S. Farm Bill. The idea was to provide a safety net for farmers who were so embattled by price volatility and environmental calamity (both inevitable features of a production system that operates at the mercy of weather and global economics) that many of them wanted to stop farming altogether. Programs encouraged farmers to take some land out of production to allow the land to naturally rejuvenate as well as to keep prices high by preventing the market from being flooded. Storage programs for commodity crops (resources that serve as raw materials for other products) like corn and soybean also helped stabilize prices since extra could be stored in good years, and supplies could be tapped in bad years. The original Farm Bill also ensured that farmers would be paid at least as much as it cost to produce the food.

U.S. Farm Bill

Legislation that deals with many aspects of the production and sale of farm-raised commodity crops.

But critics contend that the Farm Bill, which is updated every 5 years, has slowly removed these safety nets, in favor of new provisions that support behemoth factory farms, including CAFOs, at the expense of small and midsized operations. “There is nothing inherently efficient or economical about raising vast cities of animals in confinement,” writes Pollan. He points out that three federal policies in particular have propped up CAFOs: subsidies that enable feedlot operators to buy grain for less than it costs to grow, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the routine use of antibiotics in animal feed (without which, he says, so many CAFO animals could not survive), and lax regulation of wastewater treatment. “The government does not require CAFOs to treat their wastes as it would require human cities of comparable size to do,” he writes.

Two of these “struts” have recently been kicked away. The 2008 global economic crisis drove up grain prices so that even with subsidies, feedlot operators are now paying at least as much as it cost to grow the grain. And early in 2012, the FDA announced that it would no longer allow farmers to administer antibiotics to their animals without a veterinary prescription.

A similar policy in Denmark, instituted in 1999, proved successful, resulting in a 50% drop in antibiotic use and no concurrent drop in farm productivity.

KEY CONCEPT 30.7

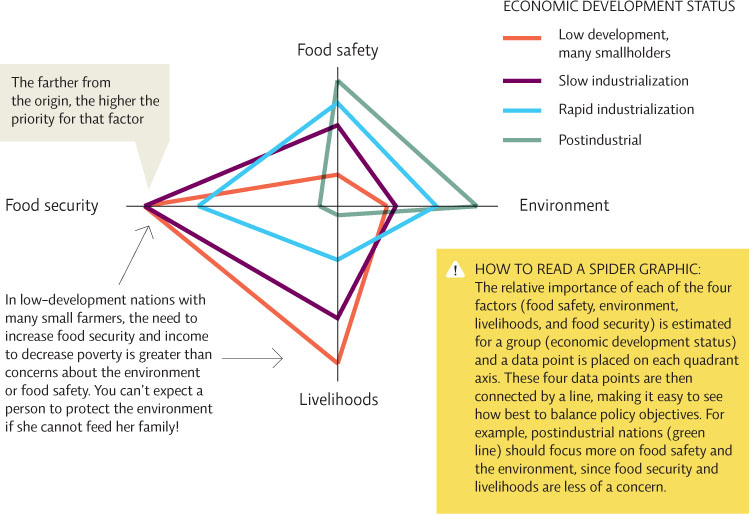

Agricultural policy must meet the immediate needs of the nation. Once food security and the economic needs of the population are met, the focus of policy generally expands to address environmental and food safety issues.

“CAFOs should also be regulated like the factories they are,” Pollan writes. They should be “required to clean up their waste like any other industry or municipality.” Yes, he admits, such policies will make meat pricier; but that is as it should be. “Paying the real cost of meat, and therefore eating less of it, is a good thing for our health, for the environment, for our dwindling reserves of fresh water, and for the welfare of animals,” he writes. “Cheap food is dishonestly priced. It is, in fact, unconscionably expensive.”

The UN FAO acknowledges that CAFO livestock may help feed a growing human population, but only if policy changes are made that support more sustainable practices. For example, capturing waste and using it as fertilizer or to generate electricity would turn it into a resource instead of a problem to be solved. Moving CAFOs away from urban centers or smaller livestock operations would prevent the spread of disease between animals and from animals to humans. Yes, sustainably produced meat will cost more: CAFO operators will have to spend money to establish better waste management systems and to adhere to stricter environmental regulations. But, to echo Pollan, that is as it should be. “The price of beef should reflect the true cost of producing it,” says Ferraro. “And that includes the environmental costs of pollution, land degradation, and water depletion.” INFOGRAPHIC 30.6

Different regions around the world face different problems, and each needs its own solution about the best way to raise livestock. The UN FAO recommends that low-income, developing nations focus more on helping their small farmers earn a living raising livestock and increasing access to affordable food for local citizens. As income increases and the percentage of the nation’s income that comes from raising livestock decreases, priorities should shift to improving food safety and reducing the environmental impacts of raising animals.

Which of the four issues shown on this spider graphic are postindustrial nations like the United States most concerned about, and which ones are low priority? Why?

Postindustrial nations are not as concerned about livelihoods and food security as they are about food safety and the environment because most citizens in their country have adequate incomes and know where their next meal is coming from. This is certainly not true for everyone (hence the line in the spider graphic does go into the food security and livelihood quadrant a little). Since food security and livelihoods are fairly secure, more of the nation’s attention and resources can go into making that food supply more safe and in growing food in a way that better protects the environment. These choices really represent an extravagance that nations lower on the economic scale cannot afford because they are still just trying to feed their people.