Laws exist to protect and manage fisheries.

For most of human history, it seemed impossible that we could ever use up the resources in something as vast as the ocean, which takes up 70% of the planet; but in recent decades, that thinking has begun to change. As human populations swell and fish populations plummet, scientists and lawmakers around the world are struggling to reverse the damage that’s already been done and to protect our fisheries from further decline.

They started by enacting legislation. For centuries, most nations defined their territorial waters, or exclusive fishing zones, as reaching 12 nautical miles (22 kilometers) off their coastlines. But in the 1960s, it became clear that such zones were no longer adequate. Wide-ranging industrial ships—floating factories, replete with freezing and processing technology—had long freed fishers from the shackles of time and distance. They could now pursue any fishery they liked, no matter how far from their home country; and with no rule of law to constrain them, they could also stay as long as they pleased and take as much as they wanted. As the Atlantic cod would eventually show, no fishery stood a chance against a global army of such ships.

One response to this problem was the creation of exclusive economic zones (EEZs)—zones that extend 200 nautical miles (370 kilometers) from the coastline of any given nation, where that nation has exclusive rights over marine resources, including fish.

exclusive economic zones (EEZs)

Zones that extend 200 nautical miles from the coastline of any given nation, where that nation has exclusive rights over marine resources, including fish.

For a long time, most countries, including the United States, simply kicked other nations out of their fisheries while still allowing their own fishers to take as much as they pleased. But with fisheries around the world at or near collapse, fisheries managers have started cracking down. In the U.S. cod fisheries, for example, officials have set strict limits on the amount of all ground (bottom-dwelling) fish of any species that any vessel may take. Once a vessel reaches its predetermined limit, it must stop fishing for the season.

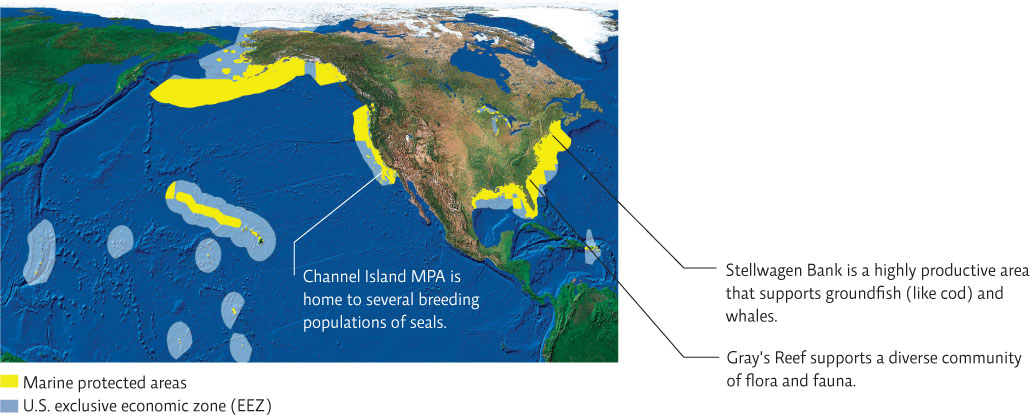

Fisheries managers have also created more than 1,500 marine protected areas (MPAs)—discrete regions of ocean that are legally protected from various forms of human exploitation. Many of these MPAs protect only specific elements within the area—certain species of fish, a discrete portion of the habitat (like a spawning ground), or a cultural artifact (like a sunken ship). But at least some of them are fully protected marine reserves—“no take” zones where absolutely nothing may be disturbed by human hands. Sea life is recovering in many MPAs, giving us reason to be encouraged. INFOGRAPHIC 31.5

marine protected areas (MPAs)

Discrete regions of ocean that are legally protected from various forms of human exploitation.

marine reserves

Restricted areas where all fishing is prohibited and absolutely no human disturbance is allowed.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) provide varying degrees of protection for different species, depending on the area and the need. Exclusive economic zones (EEZs) extend 200 nautical miles from the coastline of any given nation, giving that nation exclusive rights over marine resources, including fish. Both MPAs and EEZs can help protect species at risk by restricting harvests and use in the area.

How can the establishment of an exclusive economic zone help protect fisheries when the nation with rights to that zone can fish there?

It prevents other nations from fishing there too, thus reducing potential fishing pressure. It also allows a nation to better manage fisheries because it has the legal means (laws imposed on its own citizens) to regulate fishing that occurs there.

The Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, first passed in 1976, is the primary law governing marine fisheries management in U.S. federal waters. The 1996 amendments focused on rebuilding overfished fisheries, protecting ecosystems, and reducing bycatch. Amendments in 2006 added market-based programs like catch-share (similar to “cap-and-trade” programs that regulate the release of air pollutants; see Chapter 20) that appear to be helping with the recovery of some fish stocks.

But managing a resource that makes up 70% of the planet is no small feat, and despite these efforts, fisheries have continued to dwindle. Part of the problem is the enormous amount of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing—between $4 and $9 billion worth every year. In some fisheries, 30% or more of the annual catch is harvested with illegal gear, in prohibited areas, or at prohibited times.

Here’s another problem: So far, fisheries management has been based on incomplete science. For example, The State of the World’s Fisheries and Agriculture, a biannual report issued by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) that estimates fish stocks and makes recommendations for maintaining fisheries sustainably, bases its conclusions almost exclusively on population studies—research that uses characteristics like a species’ rate of reproduction and time to reach adulthood to determine how many fish can be taken without jeopardizing the fishery. Successful management requires more than that. To maintain individual species at sustainable levels, fishery managers need to consider the entire ecosystem in which the species resides—not just the abundance of a given fish, but the relative populations of the fish they feed on, the overall health of their spawning grounds, and a host of other factors.

KEY CONCEPT 31.5

Options to protect fisheries include national exclusive economic zones that reduce fishing pressure from other nations, legal protections that limit fish harvests or protect specific areas from various human impacts, and the promotion of sustainable fishing techniques.

The Marine Stewardship Council, an international, nonprofit organization that certifies fish food products as sustainable, defines a sustainable fishery as one which ensures that fish stocks are maintained at healthy levels, the ecosystem is fully functional, fishing activity does not threaten biological diversity, and the fishery is managed effectively. In 2014, the council recognized 185 certified fisheries; another 143 were undergoing assessment for certification.

sustainable fishery

A fishery which ensures that fish stocks are maintained at healthy levels, the ecosystem is fully functional, and fishing activity does not threaten biological diversity.

Of course, no management strategy can reconcile limited supplies with rising demand, which is why, even as net-pen operations like the ones in Frenchman Bay, Maine, proliferate around the world, more and more scientists are saying that the real solution to our fish problem won’t be found in the ocean at all.