Biofuels can come from unexpected sources.

Back in Minnesota, Tilman set about testing to see why half his grasslands seemed resistant to drought. After trying “a whole variety of things,” Tilman and his team came to a simple conclusion: The plants growing in the most diverse areas—those with up to 20 species of grasses and flowers—were the most able to weather periods of drought. Tilman was baffled. Why should plants competing with each other be more successful during a drought?

He and his team of ecologists decided to study the question empirically. They spread out under a bright blue sky at the Cedar Creek Reserve in Minnesota and planted a smorgasbord of seeds among 152 plots, each plot roughly the size of half a tennis court. The plants began to sprout: gold bunches of junegrass, stately spires of dark blue lupine, bright yellow tufts of goldenrod, and tall, spiky western wheatgrass. Some plots had only 1 species, some 2, others up to 16. Each plant was a perennial, meaning it would grow back every year, differing from annual plants such as corn and soybeans, which must be replanted each year. The team used no fertilizer and watered plots only in the first few weeks after planting.

perennial

Plants that live for more than a year, growing and producing seed year after year.

annual

Plants that live for a year, produce seed, and then die.

KEY CONCEPT 32.2

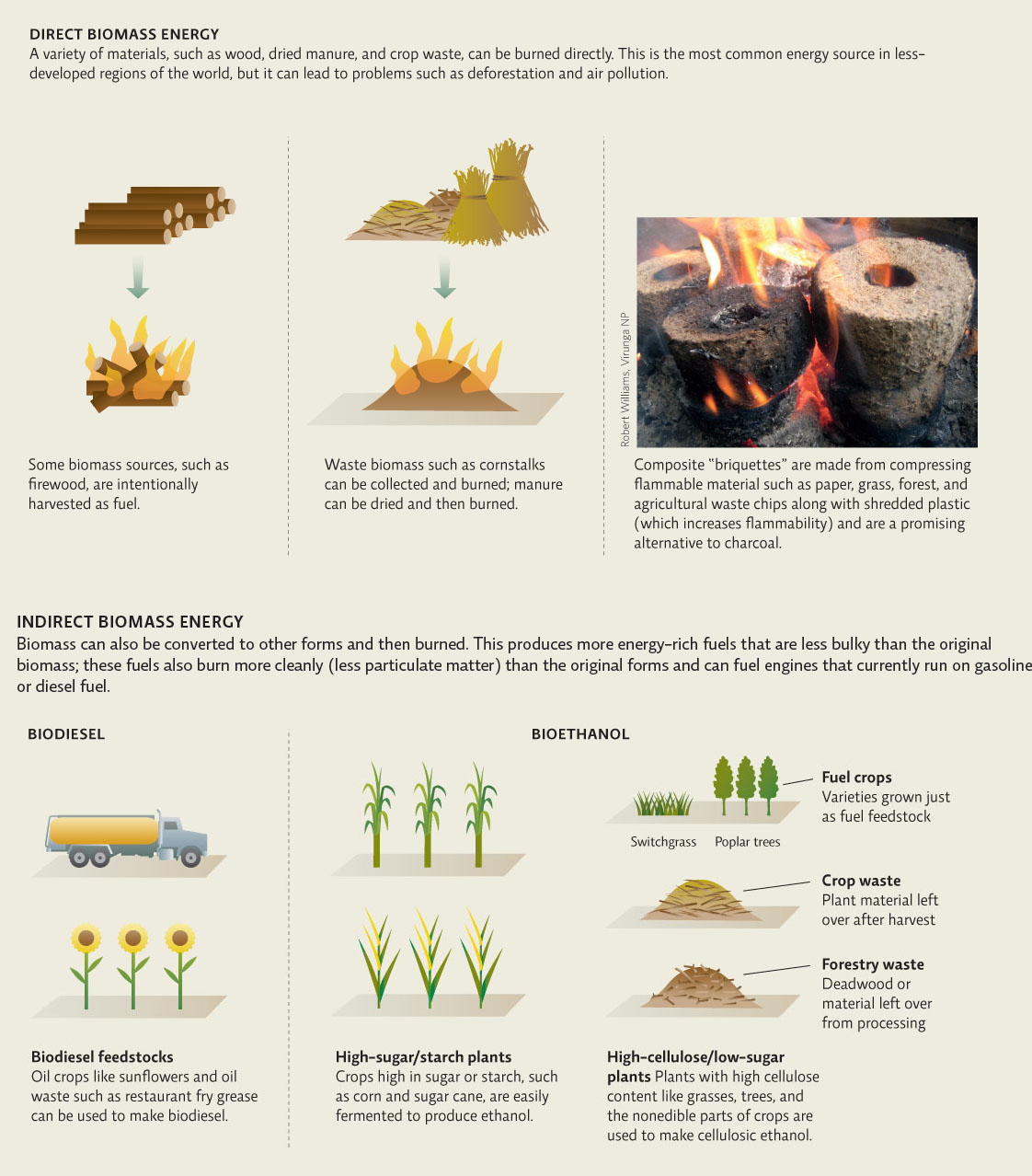

Biomass can be harnessed for energy by being burned or by being converted to other fuels that can be burned; even waste can be used to generate energy.

One of the species was switchgrass, a common North American perennial that grows thick and tall (up to 12 feet), with roots penetrating 10 feet into the soil. As Tilman watched his plants grow, he was not the only person thinking about switchgrass. The crop was rapidly becoming a household name for another reason—as a potential source of biofuel.

Often, biofuels are derived from fuel crops, which are specifically grown to make biofuels. For instance, bioethanol can be derived from crops such as corn and sugarcane during a process of fermentation and distillation, similar to that used to make alcoholic beverages. Biodiesel, a different kind of biofuel produced from oils, is most often made from high-oil crops like soybeans. INFOGRAPHIC 32.1

fuel crops

Crops specifically grown to be used to produce biofuels.

bioethanol

An alcohol fuel made from crops like corn and sugarcane in a process of fermentation and distillation.

biodiesel

A liquid fuel made from vegetable oil, animal fats, or waste oil that can be used directly in a diesel internal combustion engine.

Biomass (material of biological origin) can be burned directly or converted to other forms of fuel, such as bioethanol or biodiesel. Some crops are specifically grown just for fuel production (fuel crops) but waste material can also be used. As long as the feedstocks (biomass sources used in production) are grown and harvested sustainably, biofuels are a sustainable resource.

Robert Williams, Virunga NP

What is the main difference between direct and indirect biomass energy?

Direct biomass fuel sources are burned in their original form whereas indirect sources of biomass energy are first chemically converted to a different form such as ethanol or diesel fuel and then burned.

Today, ethanol is primarily used as an additive, mixed with gasoline to produce a cleaner-burning fuel. It’s also more corrosive than gasoline, so mixtures at the gas pump typically contain no more than 10% ethanol (E10 fuels). Some so-called flex fuel vehicles are equipped to use up to 85% ethanol mixtures, and thousands of these vehicles are on the road today. Because ethanol has only about two-thirds of the energy found in gasoline, however, it is not suitable for high-demand engines like those in airplanes and large trucks. Biodiesel, however, is more energy-rich than ethanol, and can be used in these applications; it can also be used directly in diesel engines, with little or no modification.

There’s another convenient source of biofuels—biowaste, often in the form of organic leftovers such as crop residues, garbage, or manure. For instance, even though ethanol usually comes from corn and sugarcane, it can also be produced from the stalks, husks, and leaves of plants left over after a crop has been harvested. Any kind of organic material has the potential to be converted to liquid biofuels such as ethanol, or to a gaseous product similar to natural gas known simply as biogas.

The idea of converting waste to energy is appealing: It has the dual benefit of both producing energy and dealing with waste at the same time. For instance, communities are struggling to deal with methane released from decomposing landfill waste, which acts as a potent greenhouse gas, each molecule trapping 25 times more heat in the atmosphere than one of carbon dioxide. Some communities are now working to capture that gas for energy use. Of 2,300 municipal solid waste landfills in the United States, more than 450 have landfill gas projects, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

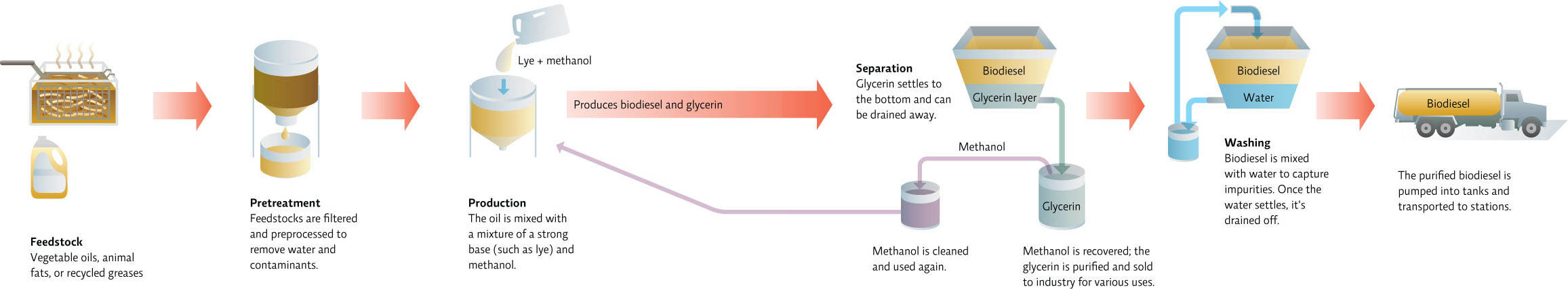

Biodiesel can also easily be made from waste such as animal fats or waste oil. Indeed, a new industry is emerging around the disposal of used fryer oil from restaurants; once a liability that restaurants paid to have hauled away, this oil can be picked up free of charge by biodiesel entrepreneurs who turn it into a fuel that can be sold to local diesel users.

At the moment, biodiesel comprises only a small portion of the biofuels produced, and it cannot be used in gasoline engines. But biodiesel buses and recycling trucks are on the road all around the United States. Currently, biodiesel is the only biofuel to be certified by the EPA, having passed the safety tests required by the Clean Air Act.

Biodiesel can also be produced on a small scale. Across the United States, communities are taking matters into their own hands and forming small biodiesel cooperatives that produce relatively small amounts of biofuel for personal use. In Burlington, North Carolina, T-shirt manufacturer Eric Henry and his friends collect used vegetable oil from 12 local restaurants and pass it through a small biodiesel processor behind Henry’s T-shirt plant. “We do it for interests beyond saving money,” says Henry in a soft Southern twang. “We do it for environmental reasons, for air quality, and for the local community.” INFOGRAPHIC 32.2

Garbage and agricultural, industrial, and food waste can be used to create a variety of biofuels. Biodiesel can be produced from leftover used restaurant fryer oil, or any oil waste product, such as waste from slaughterhouses. It also has the advantage of being a rather simple production process suitable for large or small scale. Small and midsized operations like Clean Energy Biofuels, located in Atlanta, Georgia, and Knoxville, Tennessee, serve the local community by picking up waste oil from local restaurants, converting it to biodiesel, and then selling it to local users.

What are some advantages of using waste material to produce biofuels?

It uses a readily available material as a feedstock (waste) and at the same time it reduces our need to find a way to dispose of or deal with the waste. Using waste also decreases the need to grow fuel crops, thus either freeing up land for food crops or allowing the land to go uncultivated and remain in its natural state.

People have spent the past 100 years trying to use biomass to power engines: Henry Ford’s first Model T, rolled out in 1908, was designed to use ethanol as fuel. But it wasn’t until the second half of the 20th century that biofuels became big business—and, more recently, a hotbed of controversy.