Endocrine disruptors cause big problems at small doses.

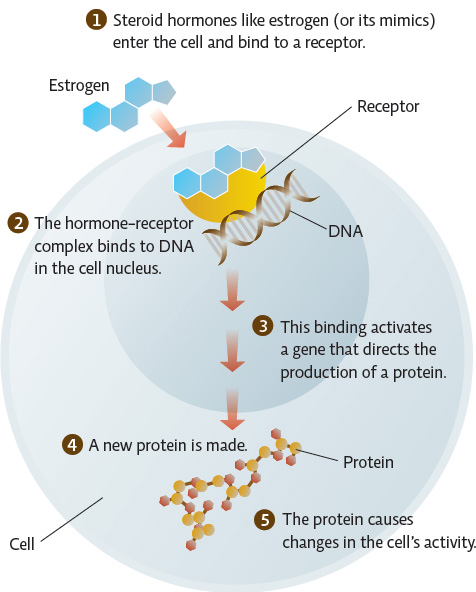

As their name suggests, endocrine disruptors interfere with the endocrine system, typically by mimicking a hormone or preventing a hormone from having an effect. Estrogen is a hormone that plays many roles in the body; its main task is to guide reproduction and development in both males and females. BPA is an estrogen mimic; it binds to the body’s cellular estrogen receptors and triggers the same effects that actual estrogen would trigger. In the wild, chemicals like this have been shown to cause feminization of males (even sex changes), as evidenced by lower sperm counts and the production of egg proteins normally produced only by females. INFOGRAPHIC 3.5

endocrine disruptor

A substance that interferes with the endocrine system, typically by mimicking a hormone or preventing a hormone from having an effect.

hormone

A chemical released by organisms that directs cellular activity and produces changes in how their bodies function.

receptor

A structure on or inside a cell that binds to a particular molecule, thus allowing the molecule to affect the cell.

Steroid hormones like estrogen (and its mimics) pass into cells, where they bind to DNA and actually “turn on” genes. These effects can be far-reaching since the activated genes may affect other genes and many cell processes, having many later effects.

Do you think that the change in cellular activity that results when estrogen or an estrogen mimic binds to its receptor is immediate, or does it take a while? Explain.

It takes a while because there are several steps involved in producing a change in the cell’s activity. Estrogen must first bind to DNA and then initiate the production of a protein. It is this protein that affects cellular activity.

KEY CONCEPT 3.6

The threat posed by endocrine disruptors is difficult to determine because they may have different effects at different times in life and because they can have greater effects at very small doses than at larger doses.

In humans, we know that sperm counts are down among men and that puberty onset is earlier in both boys and girls than it has ever been before. We also know that 95% of the U.S. population has trace amounts of BPA in their urine, and since there are no known natural sources of BPA, this suggests that it is leaching from our food and beverage containers into our bodies. No one can say for sure whether one fact (changes in sexual development) is related to the other (BPA in our systems), but because hormones control the development of body organs, scientists are especially concerned about the exposure of developing fetuses, newborns, and infants to endocrine disruptors.

Endocrine disruptors are curiously different from most other chemicals, where the relationship between dose and effect is linear (the more you ingest, the sicker you get—”the dose makes the poison”). Endocrine disruptors can have one set of effects at a very low dose and no effects (or much different effects) at higher doses.

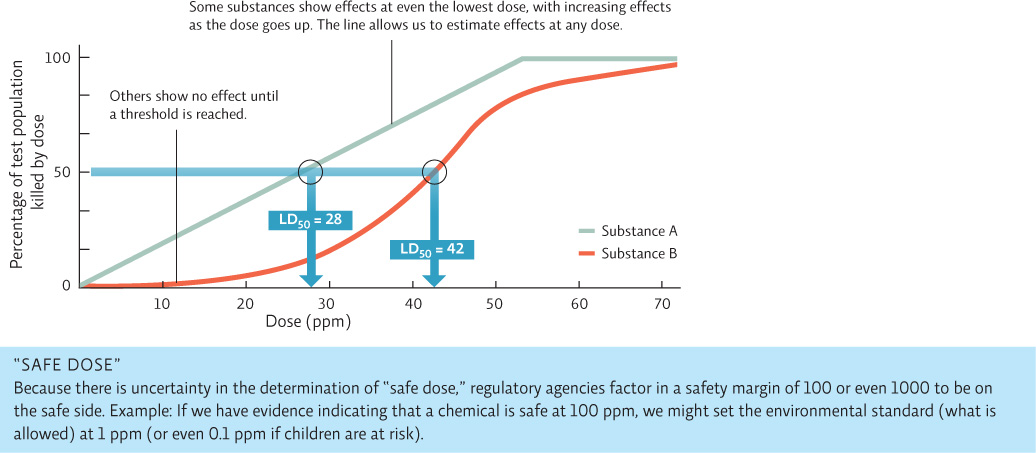

To track the effects of a dose of a chemical, toxicologists use data from in vitro and in vivo studies to create a dose–response curve, from which they can calculate an LD50 (lethal dose 50%), the dose that would kill 50% of the population. The lower the LD50, the more toxic the substance. INFOGRAPHIC 3.6

dose-response curve

A graph of the effects of a substance at different concentrations or levels of exposures.

LD50 (lethal dose 50%)

The dose of a substance that would kill 50% of the test population.

Dose-response studies evaluate the effect of a toxic substance at various doses (on animals or cells). Knowing the LD50 allows us to compare toxics directly— that is, which are more toxic than others. Charting the actual change in effect as the dose increases (the “dose response”) allows us to predict effects at doses other than those tested. We can also determine if there is a threshold of exposure that must be reached before harmful effects are seen.

Consider substance C that has an LD50 of 50 ppm. Is substance C more or less toxic than substances A and B?

An LD50 of 50 ppm is less toxic that substance A or B.

Because endocrine disruptors like BPA have different effects at low and high doses, LD50s and dose–response curves are much trickier to calculate, and a “safe dose” is much tougher to determine. “We can’t just find the threshold dose, where effects are first seen, and test higher doses from there to see what the impact will be,” says Frederick vom Saal, a biologist at the University of Missouri who has spent two decades studying low-dose effects of BPA. “For endocrine disruptors, we have to test the effects of high doses and low doses separately.”

Early claims of BPA safety did not take this detail into account. In the late 1980s, when EPA and FDA scientists were testing the chemical, they started with very high doses, given to rats, lowered the dose until they saw no adverse effects, and then stopped. As is the usual practice, a “safe dose” was established by dividing that “no effect” level by 1,000, to account for the possibility that humans might be more sensitive than lab animals or that some people, such as children and elderly or sick individuals, might be more sensitive than others.

This high-dose assessment is the basis for statements like the one Steven Hentges, spokesperson for the American Plastics Council, made to the press when the 2008 NTP report came out. “At the rate of migration into food,” he told hordes of reporters, “a consumer would have to ingest more than 1,300 pounds of food and beverage in contact with BPA every day for a lifetime to exceed the EPA safety limit.” Like the scientists whose data he was citing, Hentges was not considering the possibility of separate low-dose effects.

But it turns out that, thanks to one unfortunate chapter in our chemical history, we already have a very good idea of what low doses of estrogen mimics can do to humans. Between 1938 and 1971, doctors used the estrogen mimic diethylstilbestrol (DES) to prevent premature labor in expectant mothers. Thirty years later, when a higher incidence of reproductive abnormalities started showing up in the population, epidemiologists traced it back to DES given to pregnant mothers.

The DES research gave scientists an important tool for future estrogen mimic studies. In the course of confirming the chemical’s toxicity, toxicologists discovered a particular strain of mouse that, when given DES—or any other estrogen mimic, for that matter—responded exactly as humans did. “It’s a rare human—animal corroboration,” says vom Saal. “It gives us an unprecedented degree of certainty about how well these mice studies relate to humans.”

Back in 1997, when vom Saal tested low doses of BPA on these rodents, he found a litany of effects: increased postnatal growth in both males and females, early onset of sexual maturation in females, decreased testosterone and increased prostate size in males, altered immune function and increased mortality of embryos. Over the years, as other scientists replicated these data, more and more of them began to worry that, at low doses—such as the quantities that leach from plastic containers into food and drinks—BPA might be particularly dangerous for pregnant mothers, developing fetuses, and young children.

An equal number of researchers thought that developing fetuses were safe from any potential effects. They reasoned that BPA would be broken down in the mother’s gut and excreted in her urine long before it had a chance to reach the womb. Even if the gut failed, they thought, BPA would never get past the placenta.

According to one 2002 study of 37 pregnant women, they were mistaken. In that study, researchers found BPA not only in maternal blood but also in fetal blood and the placenta. Although no one could say for certain whether the quantities that reached the fetus were enough to cause harm, this study and others like it were enough to convince some scientists that BPA ought to be more tightly regulated.

But when the 2008 report came out saying as much, a firestorm erupted.