Critical thinking gives us the tools to uncover logical fallacies in arguments or claims.

A wide range of media outlets jumped on the NTP report, producing scores of articles that read a lot like this one:

Tests performed on liquid baby formula found that they all contained bisphenol A (BPA). This leaching, hormone-mimicking chemical is used by all major baby formula manufacturers in the linings of the metal cans in which baby formula is sold. BPA has been found to cause hyperactivity, reproductive abnormalities and pediatric brain cancer in lab animals. Increasingly, scientists suspect that BPA might be linked to several medical problems in humans, including breast and testicular cancer.

While the article is factually correct, it commits several errors of omission. By failing to explain the high degree of uncertainty (similar studies reached different conclusions, and scientists had yet to reach any sort of consensus about what the risks might be), the author creates the impression that the risks are far more certain, and dire, than they actually are. Hundreds of articles in dozens of publications followed a similar tack, and before long, the story was shortened, in the public’s mind, to one simple statement: BPA causes cancer.

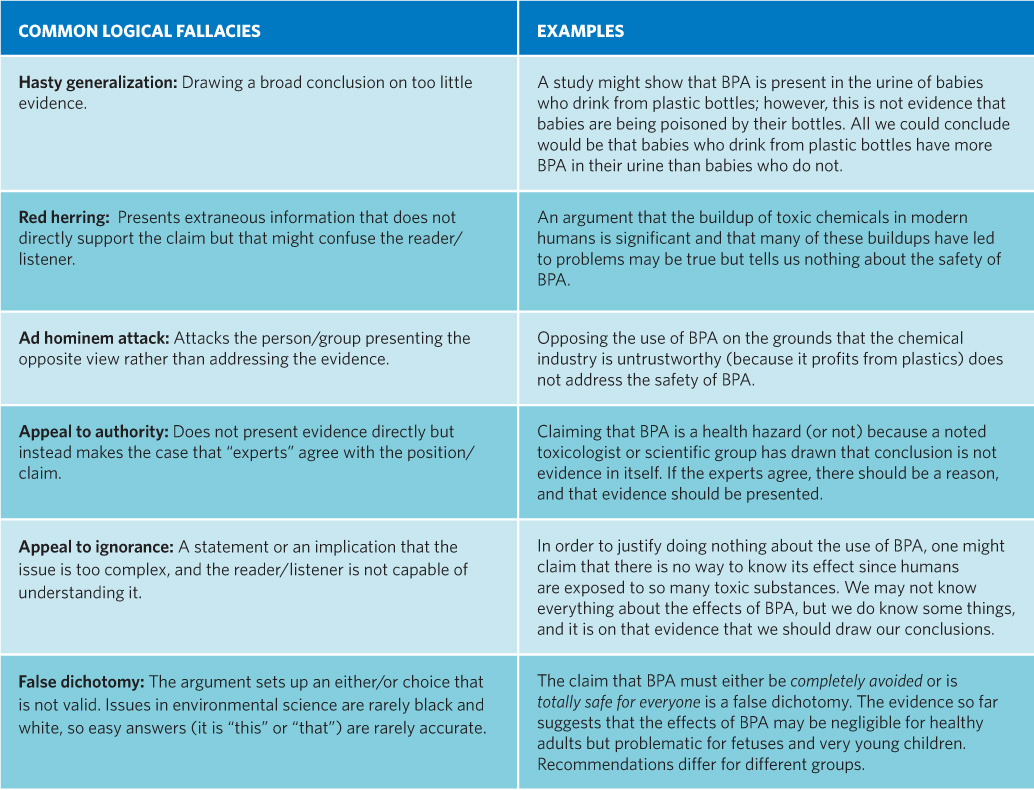

Almost immediately, environmental and consumer groups began calling for a nationwide ban on the chemical. These groups frequently attacked the plastics industry, suggesting that because large, powerful companies profited handsomely from BPA-made products, they had an incentive to downplay or even suppress troubling data. Such red herring and ad hominem attacks succeeded in stirring up the public’s fears but told them nothing about whether BPA was actually safe. TABLE 3.1

The plastics industry countered by repeatedly reminding the public that neither the EPA nor the FDA had moved to ban BPA from use and that the recent NTP report cited only “some concern” about safety. This was also true. But it ignored the fact that a small army of National Institutes of Health–funded scientists had long expressed concerns about the purported dangers of low-dose BPA exposure and were now urging regulatory agencies to at least set a new, lower exposure limit.

Logical fallacies are arguments used to confuse or sway a reader or listener to accept a claim/position in the absence of evidence.

Which logical fallacy do you feel is the hardest to recognize and might slip by the average person? Why?

Answers will vary but should be supported.

KEY CONCEPT 3.7

Critical thinking allows us to logically evaluate the evidence behind a claim or conclusion to determine whether it is indeed supported by the evidence.

Average consumers were left to figure out for themselves which side to trust: Were environmental activists exaggerating, or was BPA truly dangerous? Why did some scientific studies show deleterious effects from the chemical, while others did not? More importantly, what precautions could, or should, individuals take?

Critical thinking is the antidote to logical fallacies; it enables individuals to logically assess and reflect on information and reach their own conclusions about it. The skill set can be broken down into a handful of tenets, or measures.

critical thinking

Skills that enable individuals to logically assess information, reflect on that information, and reach their own conclusions.

logical fallacies

Arguments that attempt to sway the reader without using reasonable evidence.

Be skeptical. Just like a good scientist, a nonscientist should not accept claims without evidence, even from an expert. This doesn’t mean refusing to believe anything; it simply means requiring evidence before accepting a claim as reasonable. For example, a Science News article, “Receipts a Large and Little-Known Source of BPA,” quoted a researcher as saying that he believed BPA from paper cash register receipts “penetrated deeply into the skin, perhaps as far as the bloodstream.” The actual research documented the amount of BPA in the receipts and recovered from the surface of fingers that held a receipt, not the amount in the bloodstream of individuals who handled the receipts. A skeptical reader would therefore question the inference that BPA from receipts enters the body since no evidence was presented regarding its uptake, only its presence on the skin’s surface. Perhaps BPA does enter the bloodstream through receipts, but we need evidence in order to view this claim as reasonable.

Evaluate the evidence. Is the claim being made derived from anecdotal evidence (unscientific observations, usually relayed as secondhand stories) or from actual scientific studies? If it is based on actual studies, how relevant are those studies to the claim? Were they done on primates? Rodents? Cells in a Petri dish? Or did the researchers look at human populations? Most of the BPA studies were done on rodents. As we’ll see, some of those rodents were very good models for human health effects, and some were not.

Be open-minded. Try to identify your own biases or preconceived notions (most chemicals are dangerous, most people overreact to things like this, etc.) and be willing to follow the evidence wherever it takes you.

Watch out for author biases. Is the author of the study or person making the claim trying to promote a position? Is that person financially tied to one conclusion or another? Is he or she trying to use evidence to support a predetermined conclusion?

In defense of BPA, the plastics industry frequently cites a 2004 report by the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis, which had concluded that the evidence for adverse effects from low-dose BPA was weak. Vom Saal criticized this report because it looked at only 19 of the 47 published studies available at the time. The report was funded by the American Plastics Council, and vom Saal charged that the authors chose to examine only studies that gave the desired “no effect” results. When he himself evaluated those 47 published studies, and an additional 68 new studies, he found that results (effects versus no effects) were strongly correlated with the source of funding. None of the 11 industry-funded studies found adverse effects from BPA, whereas 90% (94 out of 104) of the government-funded studies showed significant effects of one kind or another.

The report’s authors argued that they excluded studies where rats had been injected with BPA rather than fed food pellets laden with the chemical. They reasoned that because ingestion was the most common route of exposure for humans, it made more sense to feed the rodents than to inject them. They felt that effects seen in the injection studies were not relevant to humans because in humans, BPA would not enter directly into the bloodstream. Vom Saal and others disagreed. “Fetuses and newborns—the ones we are most concerned about—haven’t yet acquired the gut microbes that adults have,” he said. “So we can’t expect their digestive systems to break BPA down as efficiently as an adult digestive system might. That’s as true for rodents as it is for humans.”

As it turned out, there was another technical reason that some of the industry studies did not find low-dose effects. It had to do with the type of rodent those researchers were using. Rather than use the strain of mice that had been so instrumental in cracking the DES case, industry scientists used a strain of rat known to be highly resistant to estrogen. This was akin to stacking the deck in favor of BPA: If the rats weren’t sensitive to estrogen, there was virtually no chance that they’d be affected by an estrogen mimic like BPA. The panel that composed the 2008 report chose not to include these studies in its assessment.