Human populations grew slowly at first and then at a much faster rate in recent years.

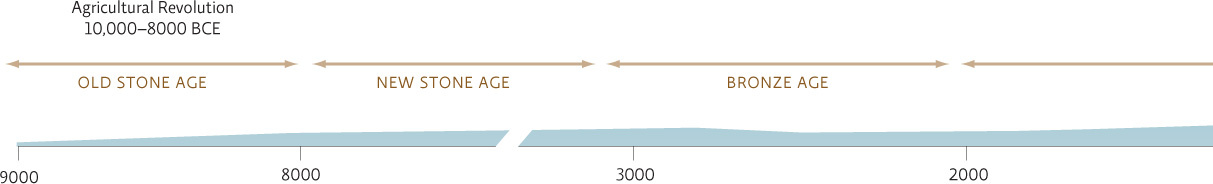

At least twice in the course of human history, global human population has hit a dramatic growth spurt. The first came around 10,000 years ago, when the Agricultural Revolution dramatically increased the amount of food we could obtain and, thus, the number of mouths we could feed. As more food translated into healthier people, lower death rates, and longer life spans, the population growth rate increased, and global population raced toward the 100 million mark. The next, much bigger, growth spurt began in the 1700s, when the Industrial Revolution ushered in a rapid succession of advances in agriculture as well as sanitation and health care—including vaccines, cleaner water, and better nutrition. Once again, death rates fell, life expectancy rose, and the population swelled. INFOGRAPHIC 4.1

population growth rate

The change in population size over time that takes into account the number of births and deaths as well as immigration and emigration numbers.

For most of human history, there have been fewer than 1 billion people on the planet.

What kinds of factors might result in a population of 16 billion by 2100 (the high estimate), and what might prevent our population from growing this large? For the medium and low estimates, what circumstances might lead to populations of those sizes?

The "high" estimate appears to be a continuation of the current trend so that suggests that nothing is done to curtail births or increase deaths. However, it is questionable whether Earth could support a population of 16 billion so other things might curtail that growth such as war, famine, or steps intentionally taken to reduce birth rates. The medium estimate might reflect steps to reduce birth rates. The low estimate might reflect lower birth rates but also higher death rates due to war, disease, famine, etc.

KEY CONCEPT 4.1

The human population grew very slowly for most of human history before the Industrial Revolution. Since then, a growth spurt has sent our population soaring past 7 billion.

In China, this cycle played out most dramatically during the latter half of the 20th century, when the country experienced a spectacular improvement in its standard of living. Between the 1950s and 1970s, life expectancy increased from 45 to 60. But as the crude death rate fell, the crude birth rate held steady. By 1949, China was home to 500 million people—triple the U.S. population at that time—making it the most populous country on Earth. By 1970, the population of China had swelled to almost 900 million: roughly one-quarter of the world’s people living on just 7% of the planet’s arable land.

life expectancy

The number of years an individual is expected to live.

crude death rate

The number of deaths per 1,000 individuals per year.

crude birth rate

The number of offspring born per 1,000 individuals per year.

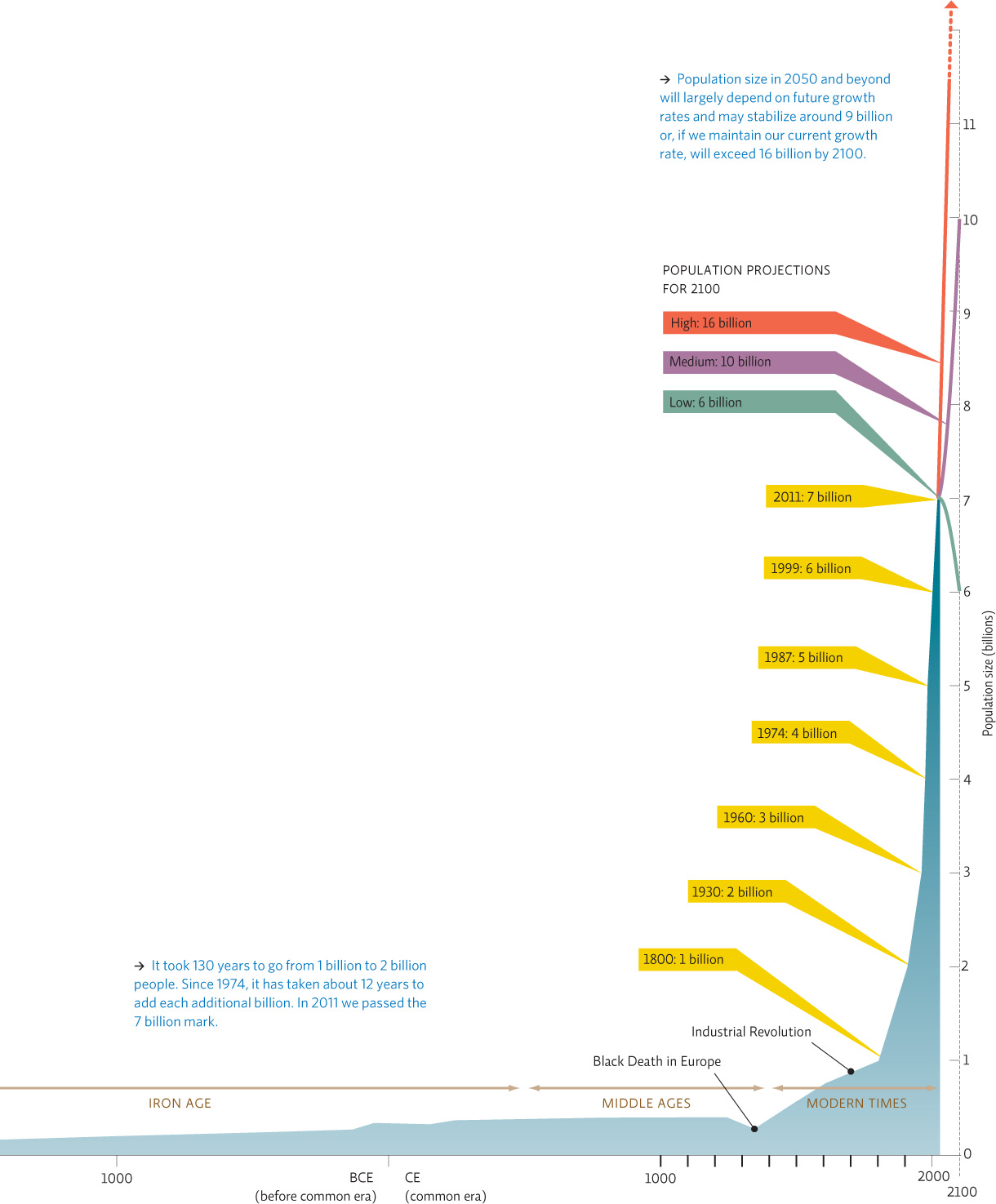

Today, China is the most populous nation, with more than 1.3 billion people, but it will soon be surpassed by India, which is projected to have 1.5 billion by 2030. Like many other nations around the world, more and more of China’s people live in big cities, with many urban areas reaching record population densities. INFOGRAPHIC 4.2

population density

The number of people per unit area.

The 10 most populous countries are not necessarily those with the largest land mass. China and the United States have roughly the same area—so China has a higher population density than the United States. Bangladesh has one of the highest population densities in the world, at almost 1,000 people per square kilometer.

What are some of the advantages and disadvantages of living in areas with high population density?

Advantages include larger job force and potential for innovation or creativity and larger and better health care and educational opportunities. Disadvantages include greater strain on the immediate environment (waste, resource depletion), spread of disease, and the potential for higher crime rates.

Migration into or out of a population also affects the size of a local population. Immigration refers to the movement of people into a given population; emigration refers to their movement out of a given population. Taken together, annual migration data and birth and death rates can tell us how quickly a population is changing in size.

immigration

The movement of people into a given population.

emigration

The movement of people out of a given population.

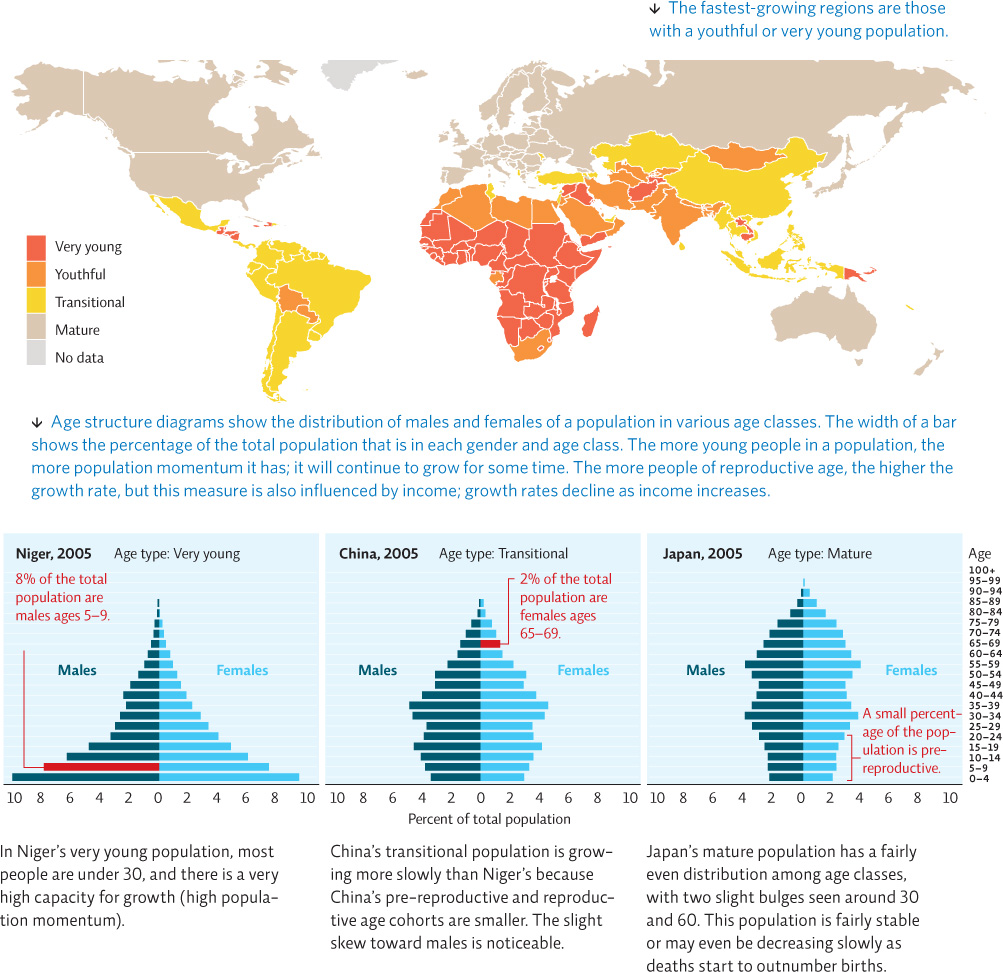

Demographers (social scientists who statistically analyze human populations and how they change over time) create a diagram that displays a population’s size as well as its age structure and sex ratio. These age structure diagrams give insight into the future growth potential of a population. INFOGRAPHIC 4.3

age structure

The percentage of the population that is distributed into various age groups.

sex ratio

The relative number of males to females in a population; calculated by dividing the number of males by the number of females.

age structure diagram

A graphic that displays the relative sizes of various age groups, with males shown on one side of the graphic and females on the other.

What percentage of the population is between 0 and 4 years of age in each of the three countries shown here (Niger, China, and Japan)?

The percent of the population between the ages of 0 and 4 years is: Niger, about 20%; China, about 6.5%; Japan, about 4%.

In China, rapid population growth became a political issue. In the late 1950s, famine claimed 30 million lives. During the 1970s, a severe shortage in consumer goods—soap, eggs, sugar, and cotton—led to strict rationing. The government blamed the country’s woes on overpopulation. Today, experts say that the real culprit was botched state planning. “China was not unlike other parts of the world at that time, in terms of higher life expectancies and growing population,” says Wang Feng, Director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy. “We could have managed, as other countries did, with better agricultural and economic policies.”

overpopulation

More people living in an area than its natural and human resources can support.

KEY CONCEPT 4.2

Populations with a lot of young people have a great deal of population momentum and will continue to grow even at replacement fertility.

Maybe so. But in the late 1970s, with two-thirds of the population under the age of 30, and the baby boomers of the 1950s and 1960s just entering their reproductive years, China’s leaders had good reason to panic. When the majority of the people in a population are young, the age structure diagram looks very much like a pyramid; there are nearly equal portions of men and women, and there are fewer and fewer people at each higher age group. However, when many people are young and have not yet reached reproductive age, the population will continue to grow rapidly over time. A population like this has population momentum; it will continue to increase for another generation, even if each couple has only two children—just enough to replace themselves when they die (called replacement fertility). If the Chinese government could not feed the mouths it already had, how in the world would it feed any more?

population momentum

The tendency of a young population to continue to grow even after birth rates drop to “replacement fertility” (two children per couple).

In 1979, China’s leaders issued a mandatory decree: No family could have more than one child. The government vowed to deny state-funded health care and education to all but the firstborn child. Parents who didn’t comply also risked losing their jobs and faced severe fines (often several times their annual income) and penalties (including a loss of government subsidies for baby formula and other foodstuffs).

Dramatic as it sounded, the idea of strictly enforced population control was not entirely new. In fact, modern societies have fretted over swelling ranks since the Industrial Revolution (that second growth spurt); that’s when an English priest by the name of Thomas Malthus first noticed that food supplies were not increasing in tandem with population. Unless something changed, he warned, we would soon have more mouths to feed than food to feed them with. And when that happened, disease, famine, and war would surely follow. According to Susan Greenhalgh, Harvard University anthropologist and author of the book Just One Child: Science and Policy in Deng’s China, such catastrophic thinking was a big part of how the Chinese government arrived at its one-child policy.

When China’s leaders enacted the policy, they promised that the policy would be a short-term one, set to expire in 30 years. By then, they said, Chinese society would have adapted to a small-family culture, and with hundreds of millions of births prevented, the quality of life would have improved substantially.