Fertility rates are affected by a variety of factors.

China was once a culture built around large, extended families and shaped by a constellation of pronatalist pressures—cultural and economic forces that encourage families to have more children. Parents and grandparents lived under the same roof; aunts, uncles, and cousins remained close by, usually in the same village. And couples had as many children as possible so that there would be enough hands to work the family farm, tend to household chores, and, most importantly, care for parents as they aged.

Desired family size (how many children a couple wants) is one of the best predictors of actual fertility (how many children a couple has); therefore, any factors that increase or decrease one’s desire to have children will significantly impact population growth rates.

KEY CONCEPT 4.3

Pronatalist pressures strongly affect desired family size, one of the best predictors of total fertility.

The need for labor is a common pronatalist pressure in agrarian societies—as are the status and prestige associated with large families and a lack of other options for women. (In many countries women’s rights and freedoms are still strictly limited.) In many developing countries, especially in Africa, a high infant mortality rate—the number of infants who die in their first year of life, per every 1,000 births—also contributes to higher fertility. Under these conditions, couples tend to have more children, which increases the odds that at least some will survive to adulthood.

infant mortality rate

The number of infants who die in their first year of life per every 1,000 live births in that year.

KEY CONCEPT 4.4

Most population growth in the recent past has occurred in less developed nations; projections for future growth continue that trend.

For centuries—right up until the 1970s, in fact—China’s total fertility rate (TFR), the average number of children a woman has in the course of her lifetime, hovered between five and six. Ironically, the most dramatic decline in that rate took place in the decade before China implemented its “one-child” policy. Between 1970 and 1979, a largely voluntary mandate known as “late, few, long” managed to cut the total fertility rate in half—from 5.9 to 2.9—just by encouraging couples to marry later, delay childbearing, and space conceptions as far apart as possible.

total fertility rate (TFR)

The number of children the average woman has in her lifetime.

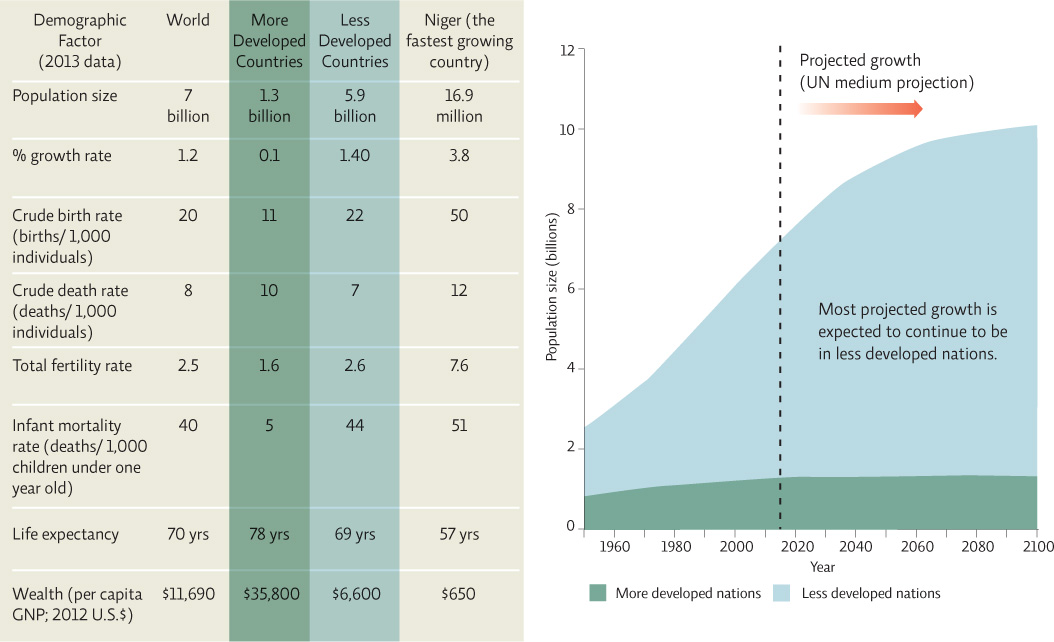

Around the world, we see big differences in the kinds of factors that influence how a population changes in size and composition. Demographic factors such as health (especially that of children), education, economic conditions, and cultural influences are, on average, quite different for more developed than they are for less developed countries. INFOGRAPHIC 4.4

demographic factors

Population characteristics such as birth rate or life expectancy that influence how a population changes in size and composition.

more developed country

A country that has a moderate to high standard of living on average and an established market economy.

less developed country

A country that has a lower standard of living than a developed country and has a weak economy; may have high poverty.

Values for demographic factors differ tremendously between developing nations like many African nations and developed nations like the United States. Most of the world’s population, as well as most population growth, occurs in developing nations, but most wealth is in developed nations. The higher death rate in developed nations is due to an aging population; the much higher infant mortality rate in developing nations reveal the differences in quality of life and health care between the two categories.

What demographic factors do you think most strongly affect the high population growth rate of Niger, the world’s fastest, growing country?

Answers will vary -- Niger has a very high infant mortality rate and a very low GNP --- it is likely that this contributes to their high birth rates and growth rate. [Later, students will see that Niger also has a very low contraceptive use rate but they also have a high "desired fertility" so providing contraceptives may not have a bit impact on their TFR.]

In China, cutting the average family size from six children down to three seemed easy. But making the leap from three children down to one proved considerably more difficult. One child meant no siblings, and in subsequent generations, no cousins or aunts and uncles, either. Who would help tend the farms? If a couple’s child died or was disabled, who would care for them when they aged? “Many Chinese families in the countryside found it unthinkable at the time to have just one child,” says Greenhalgh. Even with the penalties they faced, many resisted.

The policy’s most horrendous consequences remain sources of great speculation and worry. Many experts have said that in the early years, enforcers carried out numerous sterilizations and abortions—some estimates range as high as the tens of millions—many of them by force. But because official numbers are very difficult to come by, it’s nearly impossible to say whether such figures grossly overestimate or underestimate the problem. Ultimately, the true numbers may be unknowable.

In 1998, however, a former Chinese family planning official shed some light on the inner workings of the one-child policy, when she testified before the U.S. Congress that women as far along as 8.5 months were forced to abort by injection of saline solution, and women in their ninth month of pregnancy, or even women in labor, were having their babies killed in the birth canal or immediately after birth. The policy’s defenders say that such practices have abated, but as recently as 2001, the British newspaper The Telegraph reported that a single county in Guangdong Province was tasked with an annual quota of 20,000 abortions and sterilizations after some residents disregarded the one-child policy.

Chinese officials have argued that their focus on population control has actually improved women’s access to health care—both contraception and prenatal classes are free to all—and dramatically reduced the incidence of childbirth-related deaths and injuries.

But critics say that the human rights violations engendered by the one-child policy far outweigh any possible health gains and that, at any rate, health care is wildly imbalanced. One study, conducted by public health researchers from Oregon State University in 1990 in the rural Sichuan Province, found that women whose pregnancies were unapproved were twice as likely to die in childbirth as those whose pregnancies were sanctioned by the government. And while nearly 90% of all married women in China use contraception—compared with roughly one-third in most other developing countries—most women are not given a choice about which type of contraceptive to use; in a 2001 survey conducted by the Chinese family planning commission, 80% of women said they were compelled to accept whatever method their family planning worker chose for them. Overall, IUDs and sterilizations account for more than 90% of contraceptive methods used since the mid-1980s.

Still, there are signs of improvement. The number of sterilizations has declined considerably since the early 1990s. And in 2002, facing strong international pressure, the Chinese government finally outlawed the use of physical force to compel a woman to have an abortion or be sterilized. (Experts say that prohibition is not entirely enforced. The policy is largely exercised at the local level. And in many provinces, local governments still demand abortions.)

In any case, by 2011, China’s fertility rate had plummeted to 1.54, spurring China’s leaders to proclaim that the one-child policy had succeeded in preventing some 400 million births, and all the calamities those births would have brought—disease, more famine, overtaxed social services, and so on.

But while the drop in fertility was plain, not everyone would agree that the one-child policy deserved the credit. Critics argue that by the time the first generation of “Little Emperors” reached adulthood, many other forces had reshaped their society and the world.