Public health programs seek to improve community health.

GWD has been around for centuries but persists today only in remote populations whose only drinking water comes from ponds or other standing water sources—ideal habitat for the copepod vectors. But Ruiz-Tiben and his staff at the Carter Center were aided in their quest by a simple fact: Unlike some of those other infectious organisms, Guinea worms are utterly dependent on humans to complete their life cycle; humans are the only known reservoir for adult worms (larvae can only survive in copepods, and only for a few weeks). That meant Ruiz-Tiben and his colleagues could break the Guinea worm’s life cycle—and thus obliterate the disease—simply by changing human behavior.

Convincing villagers to filter their water before drinking it would stop new infections. Getting the villagers to apply a mild pesticide would decontaminate area ponds. And teaching people to avoid communal swimming or bathing while worms were emerging from the skin, and to treat new infections as soon as blisters emerge, would break the worm’s life cycle once and for all. Their goal was total eradication of GWD; if they succeeded, it would be only the second disease in human history (after smallpox) to be completely wiped off the face of Earth.

As straightforward as it all sounded, Ruiz-Tiben had not had much luck so far. Despite his careful detailing of the science, most of the villagers he had spoken with still believed—rather fiercely—that the sickness was delivered by angry gods, as punishment for various misdeeds. And if that explanation seemed ludicrous to Ruiz-Tiben, well, his counter-explanation—that the worms actually came from water the villagers had consumed a year prior—seemed equally ludicrous to them. He thought he might make some headway by showing them the dead bugs in the water.

Public health is a field that deals with the health of human populations as a whole. Public health epidemiologists like Ruiz-Tiben work to gauge the overall health status of a population or even of a nation. They use statistical analysis (e.g., rates of infant mortality, incidence of various diseases) to identify specific health threats to groups of people; they then recommend ways to mitigate those threats. Devising a plan of action is often the trickiest part; it requires the study of a whole host of interacting variables—from cultural and social forces (which influence things like diet and smoking habits) to economic stability or instability (which determines a given population’s access to resources) to environmental factors like water cleanliness or changes in habitat that affect disease transmission. INFOGRAPHIC 5.2

public health

The science that deals with the health of human populations.

epidemiologist

A scientist who studies the causes and patterns of disease in human populations.

The goal of public health programs is to improve the health of human populations through prevention and treatment of disease at the community level.

How does the U.S. childhood vaccination program protect the health of children too young or ill to receive the vaccinations?

Vaccinated children reduce the prevalence of the pathogens in the general population since fewer individuals contract the diseases. This reduces the chance that unvaccinated children will be exposed.

KEY CONCEPT 5.3

Public health officials track the health of a population, identifying health threats and implementing or recommending ways to mitigate those threats.

Environmental health is a branch of public health that focuses on potential health hazards in the natural world and the human-built environment; such hazards include not only things like contaminated water, air, and soil but also human behaviors—hand washing and water drinking, for example—that help determine whether those natural factors become hazards. According to the WHO, environmental hazards are responsible for about 25% of disease and deaths worldwide.

environmental health

The branch of public health that focuses on factors in the natural world and the human-built environment that impact the health of populations.

Fortunately, many environmental hazards are modifiable—that is, we can take action to change them. Like GWD, they can be mitigated (indeed, some 13 million deaths could be prevented each year) through reasonable measures. It is on these modifiable hazards—like contaminated drinking water—that environmental public health workers like Ruiz-Tiben focus their efforts.

To be sure, infectious diseases account for less of the global burden of disease than noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) like cardiovascular illness and diabetes. (Also known as lifestyle diseases, NCDs are largely determined by choices about things like diet and exercise.) In fact, NCDs cause the most deaths globally. But infectious diseases are still a major problem. They account for about 26% of deaths worldwide each year, the vast majority of them in the developing world.

noncommunicable diseases (NCDs)

Illnesses that are not transmissible between people; not infectious.

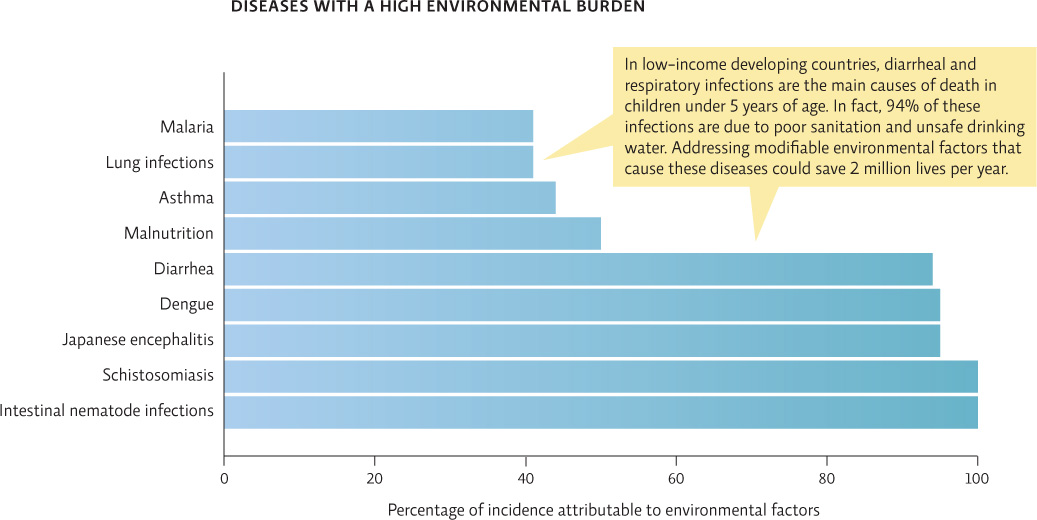

The main environmentally mediated infectious diseases are diarrheal diseases (due to environmental factors like unsafe drinking water or poor hygiene and sanitation), lung infections (linked to air pollution), and mosquito-transmitted diseases like malaria and dengue fever. INFOGRAPHIC 5.3

Modifiable environmental factors contribute to some diseases more than others. This is a result of how a particular disease is transmitted (e.g., if it is a waterborne disease) and how well a particular region is able to address environmental conditions (e.g., whether there is clean water).

Other than pathogens, what environmental factors might be contributing to asthma and lung infections?

Air pollution

KEY CONCEPT 5.4

Many parasitic infections and other health threats are linked to contaminated water and air; modifications to the environment can reduce the risk of these infections.

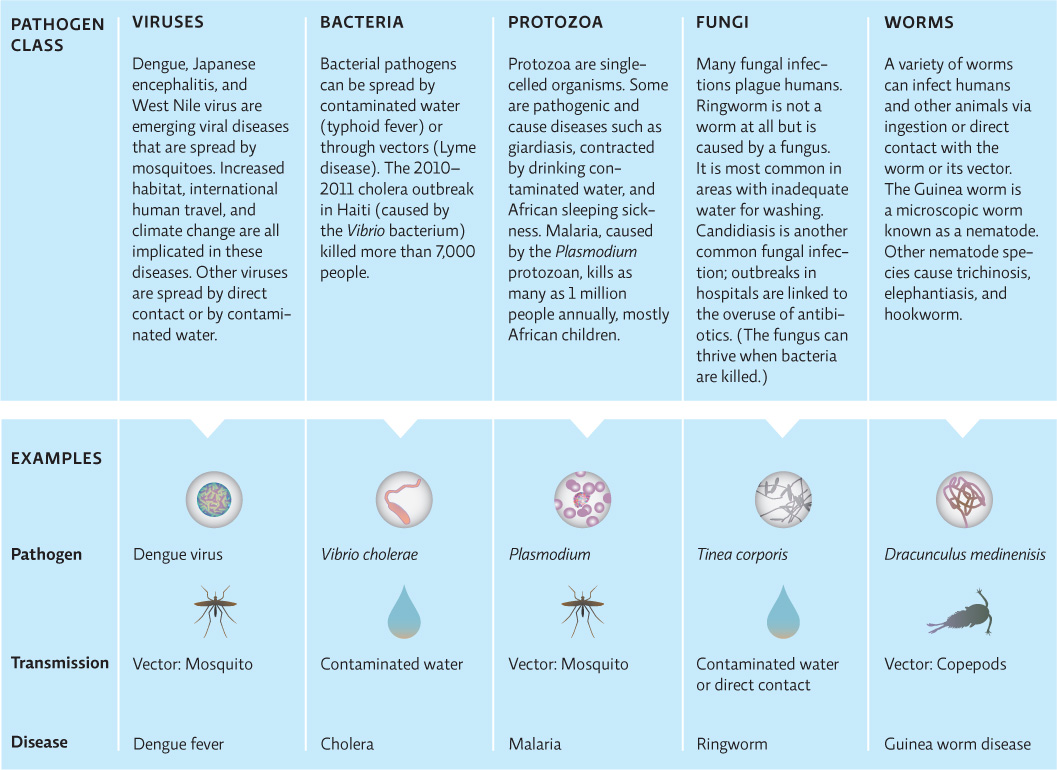

Unlike GWD, for which humans are the only host for the worm, many of these diseases are zoonotic—that is, they can spread between infected animals and humans. In fact, 75% of all emerging infectious diseases—those that are new to humans or have rapidly increased their range or incidence in recent years—are zoonotic; this includes new strains of influenza, one of the most common zoonotic diseases. About 72% of zoonotic diseases come from wildlife, a number that is increasing due to human encroachment into formerly wild areas and the bushmeat trade—killing wild animals such as primates for food. Many pathogens that infect wild primates can also infect humans, and the hunting and consumption of those animals increases the chances that individuals will be exposed to these pathogens.

zoonotic disease

A disease that is spread to humans from infected animals (not merely a vector that transmits the pathogen but another host that harbors the pathogen through its life cycle).

emerging infectious diseases

Infectious diseases that are new to humans or that have recently increased significantly in incidence, in some cases by spreading to new ranges.

Environmental changes are believed to play a role in many of these emerging infectious diseases. In the United States, recent increases in cases of West Nile virus may be linked to climate change—specifically extreme heat and drought. West Nile virus first showed up in the United States in 1999 in New York City; since then it has rapidly spread from coast to coast. High temperatures increase the ability of the mosquito vector to pick up the virus from its bird hosts. Though mosquitoes require water to breed, droughts tend to increase urban mosquito populations by increasing standing water in drains that would normally be flushed out by rains. With the hottest summer on record in Texas and other areas in the United States, 2012 broke the record for deaths due to West Nile virus (286 deaths out of 5,674 reported cases). Such outbreaks may become more common as a warming global climate allows vectors like mosquitoes to expand their range and thrive in areas where they were formerly scarce or nonexistent. INFOGRAPHIC 5.4

A wide variety of infectious agents can cause disease in humans and other organisms. The main pathogenic threats to human health are waterborne and vector-borne diseases, with the mosquito being the number-one vector of pathogens. Public health officials follow emerging infectious diseases closely; many of these diseases are zoonotic, and their recent rise is usually related to environmental factors that increase the spread of the pathogen or its vector.

How has human travel contributed to the spread of vector-borne diseases normally found only in tropical areas?

Humans who are infected in a tropical area where the infection in endemic, are now hosts for the pathogen. When they return home (or go to other areas) they may spread the pathogen to local vectors who can then spread it to other humans.