Addressing biological hazards requires environmental and behavioral changes.

In the Nigerian village where Ruiz-Tiben was working, however, the main problem was not urbanization, or habitat fragmentation, or even deforestation. Rather, the main problem was a normal human trait: resistance to change. Even after the villagers saw the bugs in the water (which he had killed with a dash of the pesticide Abate), they continued to resist using both the water filters and pesticides. When Ruiz-Tiben discovered a hidden pond infested with copepods, the women of the village formed a human shield around it so that his team could not treat it with Abate. The pond was a sacred ancestral pool, they insisted. To douse it with chemicals would invite the wrath of their gods.

KEY CONCEPT 5.5

A wide variety of pathogens cause disease and many diseases can pass from one species to another (zoonotic). The range of some diseases is expanding, further threatening human populations

The belief was anchored in an ancient history. In fact, GWD is itself ancient; it has been traced all the way back through the Old Testament and to the Egyptian mummies. Some say the very symbol of modern medicine—a serpent coiled around a staff (known as a caduceus)—derives from our treatment of GWD: To prevent the worm from breaking off at the blister, it is wound slowly around a stick as it emerges from the body—a practice that has not changed for thousands of years.

Both the worms and the copepods that carry them are native to Africa and Asia; both evolved across human history to exploit human hosts and human water sources. The copepods thrive in open, stagnant water sources—like ponds and pools formed by dams—whose availability varies by season and region. In the Sahelian zone, transmission generally occurs in the rainy season (from May to August), when shallow ponds grow deep enough to bathe in. In the humid savanna and forest zones, infections peak during the dry season (from September to January), when water holes shrivel and grow still, inviting copepods to multiply.

KEY CONCEPT 5.6

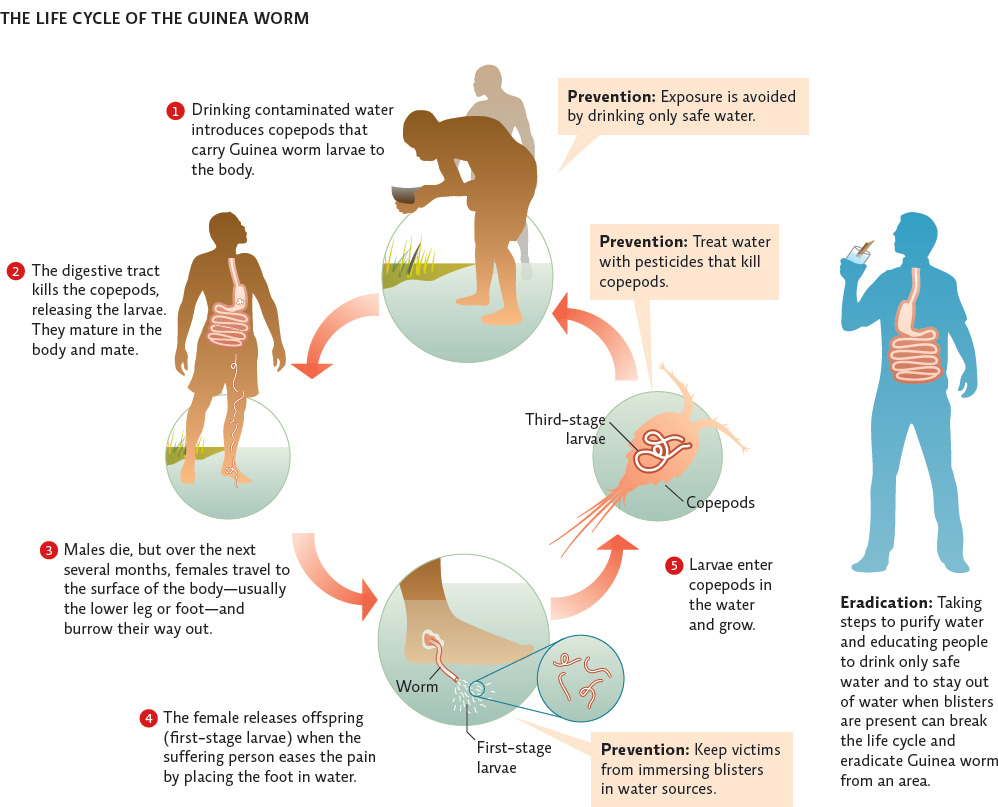

Guinea worm disease (GWD) is contracted by drinking water contaminated with worm larvae. Because humans are needed for the worm to complete its life cycle, if we can prevent exposure, GWD could be eradicated.

The only humans who come in contact with copepods are those who drink unpurified water from these sources. Like most other such people, the villagers Ruiz-Tiben was working with were poor and lived in a naturally dry area; that meant that for generations, they had had no choice but to drink and bathe in whatever water they could find. Consistent water sources—those that do not dry up when the rains pass, or evaporate during particularly hot years—were sacred. And the women were understandably leery of polluting their most treasured supply with a foreign chemical that had been made in a distant land.

It was not until a revered general from the region intervened on Ruiz-Tiben’s behalf that the women finally relented. The general, a former president of Nigeria, assured the women that the pesticide would not harm their fish but would instead keep their families from getting sick. Their ancestors, he said, would not want them to be sick. Reluctantly, the human shield broke up, and Ruiz-Tiben and his team were able to treat the pond with Abate, ridding it of copepods. INFOGRAPHIC 5.5

The Guinea worm is a parasite that spends part of its life cycle inside copepods (water fleas) and part in a human host. Humans are exposed to the parasite when they drink water contaminated with the water fleas. Because there is no other animal host in which the worm can complete its life cycle, if we can prevent infection at the source, we can eradicate this parasite.

Would it be technically possible to eradicate GWD if only step 4 of the Guinea worm’s life cycle (delivery of eggs into water) were eliminated?

Yes -- There might still be one more year or two of GWD outbreaks in people who drank contaminated water, but if no new eggs were introduced, once the current population of infected copepods died out, there would be no new infections. Of course, eliminating both exposure steps (step 1 and step 4) would increase the likelihood that no one would be infected in the future.

But as the Carter Center’s army of public health workers would soon discover, Nigeria’s challenges paled in comparison to the obstacles faced by other Guinea worm—infested countries.