Environmentally mediated diseases can be mitigated with funding, support, and education.

In Ezza Nkwubor, in southeastern Nigeria, a team of elderly men—all local villagers—stand guard over a large, silent pond. The water has been treated with pesticides, and the men’s job is to ensure that nobody with emerging worms comes into contact with it. Elsewhere, the sick have been quarantined—their wounds carefully tended and water and free food brought to them for the entire month that it takes the worm to emerge. Young boys—travelers and hunters—carry whistle-shaped cylinders tied to strings around their necks. The cylinders serve as portable filters so that the boys can drink directly from an environmental water source and still protect themselves from infection when they’re out hunting. And season after season, women teach their protégés the importance of filtering water before giving it to their families.

KEY CONCEPT 5.8

Steps that improve air quality, sanitation, and access to clean water can reduce environmental health hazards but require education and effective public policy for success.

It’s the picture of success that Ruiz-Tiben and his colleagues have envisioned for decades. “It just shows what you can accomplish when the support is there,” Ruiz-Tiben says, underscoring what has been a key lesson of the GWD eradication campaign: Implementing even the simplest technologies requires financial and political support—not only from the developed world or the international community but from the countries themselves.

Yes, it is relatively cheap and technologically simple to build pit latrines and septic systems that make proper waste disposal possible, or to build fences that can keep animals out of human water supplies, or to plant vegetative buffers that can soak up runoff before it pollutes area streams. And yes, when combined, such a roster of straightforward measures might dramatically reduce the incidence of any number of life-threatening diseases (including, for example, the diarrheal diseases that kill so many children each year). But without the money to buy wood (for fences) or plants (for buffer zones), and without know-how and “local buy-in,” such projects would never get off the ground.

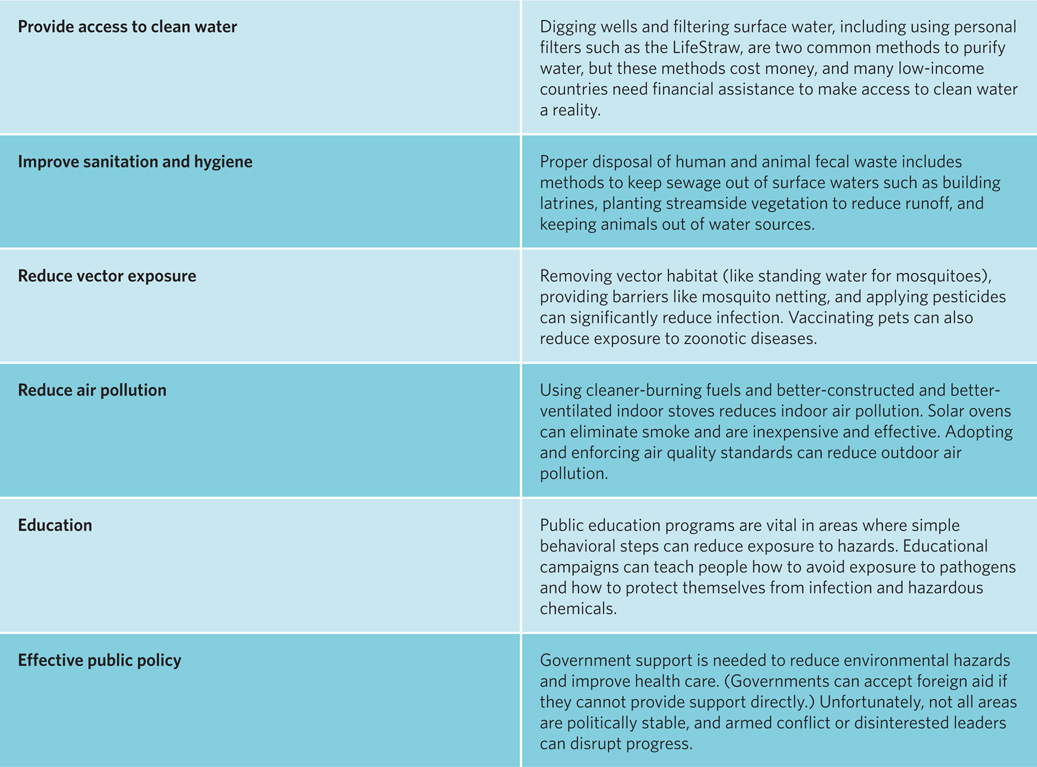

Even education campaigns that help people understand how to avoid exposure to certain infectious agents—a measure that requires almost no material support—still take a concerted effort, and thus a well-trained workforce. “It’s a lot of work to overcome preconceived notions,” says Ruiz-Tiben. “You have to present the information in a way they can relate and respond to.” TABLE 5.1

What do you think will be the biggest impediment to the eradication of GWD in Africa—the implementation of technical solutions to provide safe water or the education of people in local communities on how to reduce their exposure to contaminated water?

Answers will vary but reasons should be given for a conclusion.

To generate those things—international support, local support, and so on—environmental health workers from the developed world need, urgently, to consider the perspectives of their developing-world brethren.

Consider the case of DDT: The pesticide can go a long way toward keeping insect vectors like mosquitoes from human hosts. But when scientists in the developed world linked it to a roster of poor health and poor environmental outcomes (see Chapter 3), the chemical was banned in many regions, including places where malaria is common. Leaders in those countries were, by many accounts, responding to pressure from the developed world. Today, world leaders are reconsidering: In some malaria hotspots—certainly in places where mosquito-borne diseases kill tens of thousands of people every year—it turns out that judiciously applied DDT still provides the best mitigation strategy and may yet prove to be worth those risks.

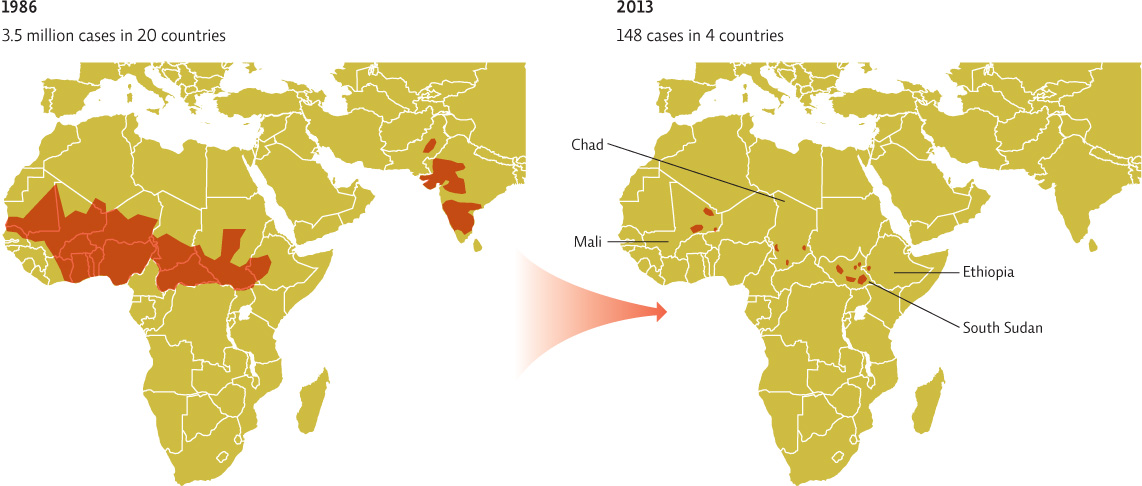

As with most other environmental problems, there are no easy solutions. To conquer GWD, environmental health workers like Ruiz-Tiben have had to battle indifference, poverty, human stubbornness, and more. In the end, those battles have paid off: In 2009, Nigeria became the 15th African country to rid itself of the ancient worm. At that time, it was estimated that just 3,500 or so cases remained throughout the entire continent, and those numbers were dwindling rapidly. By 2012, only 542 cases were reported in all of Africa; in 2013, that number had dropped to 148. Indeed, some three decades after beginning its quest, the Carter Center is finally closing in on its ultimate goal: eradicating Guinea worm disease, everywhere, once and for all. INFOGRAPHIC 5.7

Eradication programs have been in effect since 1980 and have made great progress. Prevention methods include purifying water and education about how to acquire safe water sources and handle infections to avoid reintroducing larvae into the water. Donald Hopkins, the Carter Center Vice President of Health Programs, wrote in a 2011 report that the last cases are always the hardest to wipe out, but doing so is not a matter of if but when.

Climate change is projected to reduce rainfall in some areas where GWD still persists. Will this help or hurt the fight to eradicate GWD?

It is likely to hurt it as water supplies dry up (producing more of the small stagnant pools that favor the copepods that carry Guinea worms) and people in remote areas are forced to drink unsafe water.

Select References:

The Carter Center. “Health Programs,” www.cartercenter.org/index.html.

Guimaräe, R. M., et al. (2007). DDT reintroduction for malaria control: The cost—benefit debate for public health. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 23(12): 2835—2844.

LoGiudice, K., et al. (2003). The ecology of infectious disease: Effects of host diversity and community composition on Lyme disease risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(2): 567–571.

Myers, S. S., & J. A. Patz. (2009). Emerging threats to human health from global environmental change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 34: 223–252.

PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

People in developed countries typically do not experience the same prevalence of infectious disease as do those in the developing world. However, outbreaks of illnesses like whooping cough, West Nile virus, bacterial food poisoning, and antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections do occur in the developed world and are largely preventable.

Individual Steps

•Many diseases are spread by contaminated hands. The most effective way to remove infectious bacteria and viruses is with 20 seconds or more of washing with soap and water. This is even more effective than using hand sanitizer.

•Reduce the likelihood that antibiotic-resistant bacteria will emerge by taking the entire prescription of any antibiotic you are prescribed.

Group Action

•Mosquitoes are responsible for spreading many diseases. Organize your neighbors to take preventive steps to reduce mosquito breeding, including removing containers that might trap rainwater, draining areas of standing water, and cleaning out rain gutters.

•Organize a fund-raising campaign to help purchase pipe filters such as the LifeStraw or finance well digging in areas that need access to clean water.

Policy Change

•While the Safe Drinking Water Act requires the Environmental Protection Agency to test public water supplies for contaminants and bacteria, the Food and Drug Administration is not empowered to require the same level of testing of bottled water. Ask your legislators what steps could be taken to hold bottled water to similar standards.