Chapter Introduction

CHAPTER 6

ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS AND CONSUMPTION

WALL TO WALL, CRADLE TO CRADLE

A leading carpet company takes a chance on going green

CORE MESSAGE

Human impact on Earth can be measured in terms of our ecological footprint, which is closely tied to the way we use resources. Our economic choices, both corporate and individual, tend to focus on short-term gain rather than long-term sustainability, but we can make better and more informed decisions by taking all the costs—economic, social, and environmental—of a given action into account. Using nature as a model can help us make more sustainable choices while still supporting a viable economy.

AFTER READING THIS CHAPTER, YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO ANSWER THE FOLLOWING GUIDING QUESTIONS

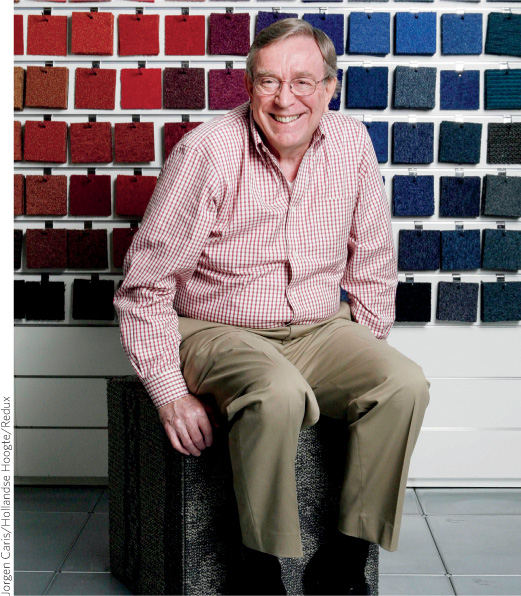

It was the summer of 1994, and Ray Anderson was feeling pretty good about things. His Atlanta-based company, Interface Carpet, was the world’s leading seller of carpet tiles—small, square pieces of carpet that are easier to install and replace than rolled carpet—and it was raking in more than $1 billion per year. One day, though, an associate from Anderson’s research division approached him with a question. Some customers apparently wanted to know what Interface was doing for the environment. One potential customer had told Interface’s West Coast sales manager that, environmentally speaking, Interface “just didn’t get it.”

Anderson was dumbfounded. The carpet industry was not generally an eco-conscious industry; after all, synthetic carpet is made from petroleum in a toxic process that releases significant amounts of air and water pollution, along with solid waste. Indeed, Interface used more than 1 billion pounds of oil-derived raw materials each year, and its plant in LaGrange, Georgia, released 6 tons of carpet trimming waste to landfills each day. “I could not think of what to say, other than ‘we obey the law, we comply,’” he recalled—in other words, his company did things by the book, in terms of the environment. Wasn’t that enough? His research associate suggested that the company launch a task force to create a companywide environmental vision. Anderson agreed, albeit reluctantly.

Desperate for inspiration, Anderson began leafing through The Ecology of Commerce, a book by environmental activist, entrepreneur, and writer Paul Hawken, which one of his sales managers had lent him. The book told the story of a small island in Alaska, on which the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had introduced a population of reindeer during World War II. Although the reindeer thrived for a time on the available plants, eventually the population exploded beyond what the environment could support. The reindeer ultimately died out because, as Anderson explained, “you can’t go on consuming more than your environment is able to renew.” Yet that, he suddenly realized, was precisely what Interface was doing—using more resources than it could possibly renew. “As I read the book, it became clear that, God almighty, we’re on the wrong side of history, and we’ve got to do something.”

Anderson realized that he had to make changes to Interface; he needed to build it into a sustainable, environmentally sound business. “I didn’t know what it would cost, and I didn’t know what our customers would pay, so it was a leap of faith,” Anderson recalled. “I knew we had to do this, but it was like stepping off of a cliff and not knowing where your foot was going to come down.”

sustainable

Capable of being continued indefinitely.