Chapter Introduction

CHAPTER 7

MANAGING SOLID WASTE

A PLASTIC SURF

Are the oceans teeming with trash?

CORE MESSAGE

We are often unaware of the waste we produce, but it profoundly affects the environment. Waste that cannot be reused or recycled simply accumulates; some of it is toxic or otherwise disruptive to living things. We can address its impact by minimizing the waste we generate in the first place, recovering and recycling waste materials, and disposing of all waste safely.

AFTER READING THIS CHAPTER, YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO ANSWER THE FOLLOWING GUIDING QUESTIONS

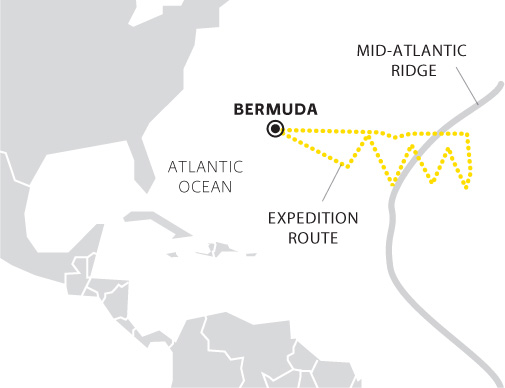

From the deck of the SSV Corwith Cramer, the surface waters of the North Atlantic looked like smooth, dark glass. The 134-foot oceanographic research vessel had set out from Bermuda just 24 hours before on a month-long expedition aimed at tracking human garbage across the deep sea.

It was a cool mid-June evening, the Sun was setting, and the crew had just launched its first “neuston tow” of the trip. Giora Proskurowski, the expedition’s chief scientist, stood watching as the tangle of mesh skidded along the water’s surface, or neuston layer, keeping pace with the ship as it went. It was hard to imagine that any garbage would be found in such a flat, serene seascape.

After 30 minutes, crew members pulled the net—dripping with seagrass and stained red with jellyfish—from the water. Sure enough, when Proskurowski got closer, he could make out scores of tiny bits of plastic glistening in the mesh. The crew members counted 110 pieces, each one smaller than a pencil eraser and no heavier than a paper clip. Based on the size of the net and the area they had dragged it over, 110 pieces came out to nearly 100,000 bits of plastic per square kilometer (about 260,000 bits per square mile).

Despite the water’s pristine look, the yield was hardly surprising. In the past 20 years, undergraduate students on expeditions like this one had handpicked, counted, and measured more than 64,000 pieces of plastic from some 6,000 net tows. That might not sound like much, given the vastness of the Atlantic and the smallness of the plastic. But the tiny bits were gathering in very specific areas, known as gyres. Gyres are regions of the world’s oceans where strong currents circle around areas with very weak, or even no, currents. Lightweight material, like plastic, that is delivered to a gyre by ocean currents becomes trapped and cannot escape the stronger circling currents. When scientists first evaluated all the data from the Atlantic Gyre, they discovered surprisingly dense patches of plastic—more than 100,000 pieces per square kilometer—across a surprisingly large “high-concentration zone.” The press and general public would come to know this region as the “Great Atlantic Garbage Patch,” cousin to a “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” discovered around the same time, and, they suspected, to several other patches scattered about the ocean.

Scientists knew where the plastic was coming from (seagoing vessels, open landfills, and litter-polluted gutters around the world). And they understood why it was being trapped in the gyres (wind patterns and ocean currents). But other questions remained. No one could say how big the Atlantic Patch actually was, or how all that plastic was affecting ocean ecosystems. Were the toxic substances found in plastic accumulating up the food chain, making their way into fish, bird, or even mammal diets? Were all those tiny bits of solid surface providing transport for invasive species? And why wasn’t there more of it? Despite a fivefold increase in global plastic production and a fourfold increase in the amount of plastic discarded by the United States, the concentration of plastic in North Atlantic surface waters had remained fairly steady across the 22 years for which data existed.

To answer these questions, Proskurowski, his team, and their captain would sail the Corwith Cramer all the way out to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, an underwater mountain range that lies about 1,600 km (1,000 miles) farther east than any previous plastics expedition had ever gone. “That’s far enough from Bermuda that getting back will be a challenge,” he wrote on the ship’s blog as land faded from view. “The same forces that drew plastic into this particular part of the ocean—namely low and variable winds and currents—will make operating a tall ship sailing vessel tricky, to say the least.” But if all went according to plan, Proskurowski thought, he and his colleagues would be the first to reach the so-called garbage patch’s easternmost edge.