How we handle waste determines where it ends up.

“It is with startling accuracy that so many tiny particles of plastic end up in such obscure but well-defined stretches of ocean,” Proskurowski wrote one morning, as the Corwith Cramer floated under the early summer sun near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. “Especially given how long and convoluted the journey they took to get here was.”

In cities of the United States and elsewhere around the world, collected solid waste makes a similar journey, one that begins when we toss something we no longer need into a trash bag that is then carried from building to curb to garbage truck, before making its way to one of several kinds of waste facilities.

Open dumps are places where trash is simply piled up. Because they are one of the cheapest ways to get rid of human trash, they are common in less developed countries, where entire communities often spring up around the dumps and people survive on what they scavenge from the waste piles. Open dumps attract pests such as flies and rats, which can be human health hazards. Open dumps also contribute to water pollution: Rain either washes pollutants away from the dump to surrounding areas or pulls it along as it soaks into the ground. If this contaminated water, called leachate, continues to travel downward, it can contaminate the soil and groundwater.

open dumps

Places where trash, both hazardous and nonhazardous, is simply piled up.

leachate

Water that carries dissolved substances (often contaminated) that can percolate through soil.

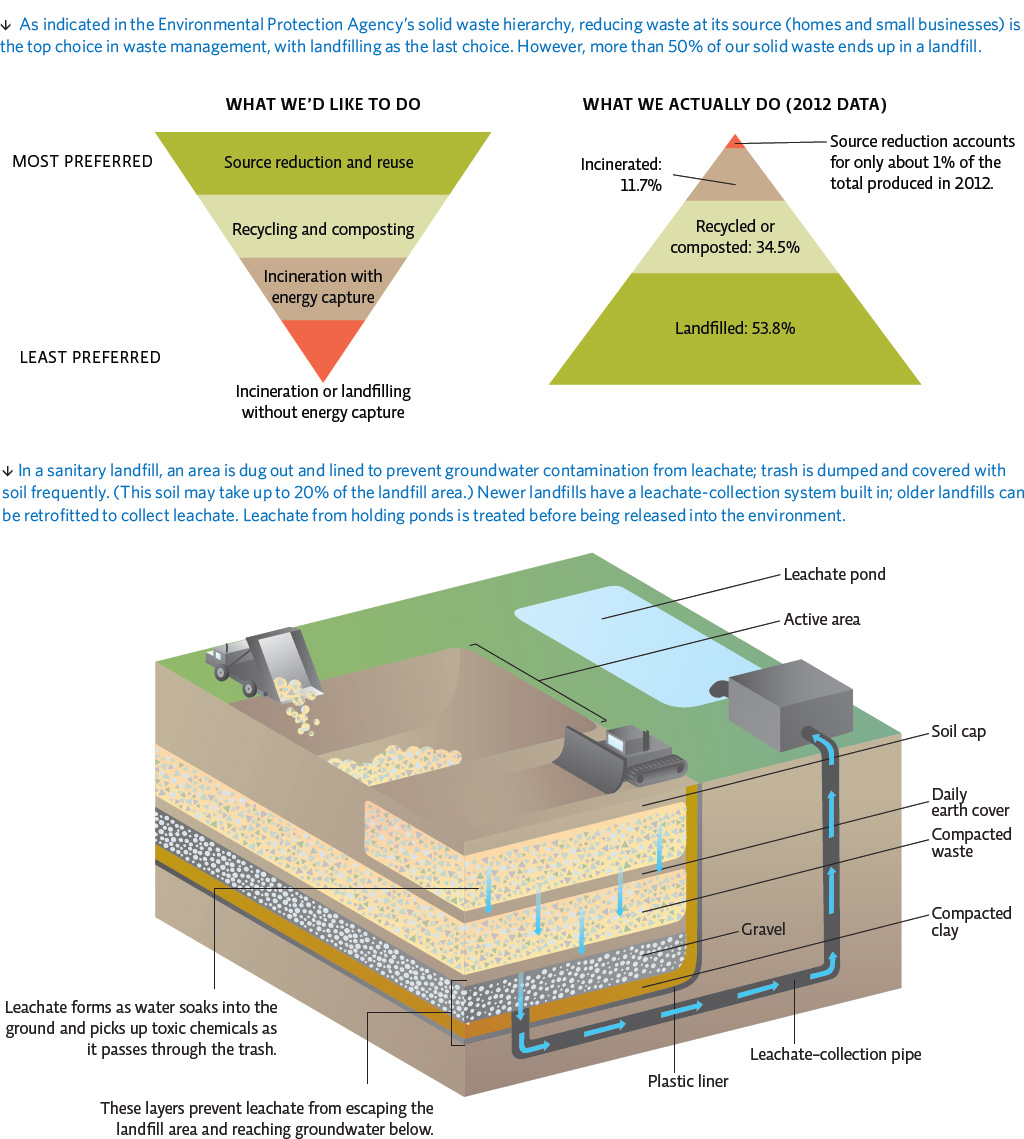

Sanitary landfills, more common in developed countries, seal in trash at the top and bottom in an attempt to prevent its release into the environment. Several protective layers of gravel, soil, and thick plastic prevent leachate from delivering toxic substances to groundwater below the landfill. The trash is covered regularly with a layer of soil that reduces unpleasant odors, thus attracting fewer pests.

sanitary landfills

Disposal sites that seal in trash at the top and bottom to prevent its release into the atmosphere; the sites are lined on the bottom, and trash is dumped in and covered with soil daily.

KEY CONCEPT 7.3

There are a variety of solid waste disposal methods ranging from problematic open dumps to the modern methods of landfilling or incineration; all of these come with trade-offs.

But there is a downside to these, too. The compacting of trash under a layer of soil excludes oxygen and water so well that the aerobic bacteria (those that require oxygen to live) and other organisms that normally decompose at least some of the waste can’t survive. Newspaper that would degrade in a matter of weeks is preserved in landfills for decades. Anaerobic bacteria (those that live in oxygen-poor environments) pick up some of the slack. But they are much slower and produce lots of methane, a combustible greenhouse gas that is 20 times more potent than CO2 (see Chapter 21). As a result, landfills are a significant anthropogenic contributor of methane in developed countries like the United States. INFOGRAPHIC 7.2

How is solid waste disposed of in your community? How does this compare to EPA’s waste hierarchy of preferred methods?

Answers will vary; landfills are the most common method of disposal in the U.S.

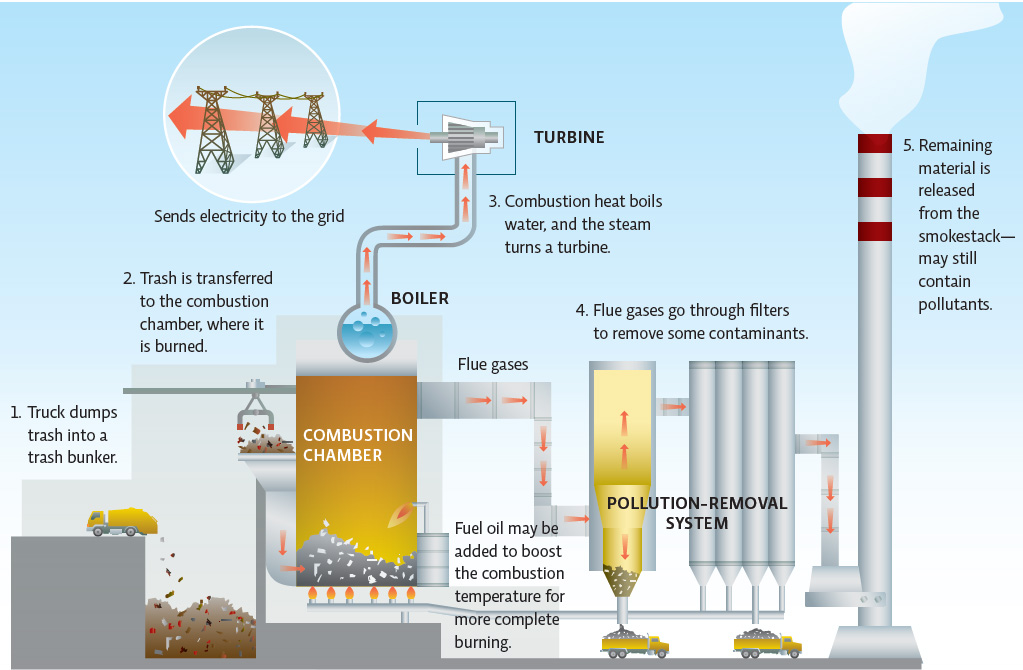

A lot of trash—thousands of tons per day—also winds up in specially designed incinerators. Burning waste in this way reduces its volume dramatically—by about 80% to 90%. And the heat produced by burning can be used to generate steam for heat or electricity. But burning waste that contains plastics and other chemicals releases toxic substances into the air, polluting air and water and producing toxic ash, which must be disposed of in a separate, specially designed landfill. Incinerators are also extraordinarily expensive to build, and tipping fees (fees charged to drop off trash) are usually much higher at an incinerator than at a landfill. INFOGRAPHIC 7.3

incinerators

Facilities that burn trash at high temperatures.

Trash can be burned at very high temperatures in incinerators (some of which are designed to also generate electricity), but in some facilities, fuel oil must be added to the mix for more complete combustion. In modern facilities, cleaning systems remove particulates, sulfur, and nitrogen pollutants, as well as toxic pollutants like mercury and dioxins. The ash is considered toxic waste and must be buried in the hazardous waste landfills. Municipal solid waste, medical waste, and some hazardous waste are incinerated in the United States.

What could be done to reduce the toxicity of incinerator ash?

Remove toxic materials like plastics and household chemicals from the trash before burning.

KEY CONCEPT 7.4

Uncollected solid waste contributes to flooding and air and water pollution. Even MSW which is disposed of using modern techniques traps valuable matter resources in landfills and incinerator ash, and contributes to environmental and health problems.

As dumpsters and landfills fill up, cities and towns begin shuffling their waste from state to state and country to country. New York City, for example, sends its trash to landfills or incinerators in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia, and South Carolina. Other cities ship trash overseas on garbage barges.

Amid this trash transfer, too much of our waste, especially our plastic, is escaping to the open sea. Much is illegally dumped. Some of it is blown there by aberrant winds from the tops of open landfills. Some is carried through faulty sewage systems or in the trickling currents of litter-polluted gutters. To be sure, not all of it is plastic, but other types of waste—textiles, glass, wood, and rubber—sink or degrade relatively quickly. Plastic just floats along. And as pieces accumulate organisms, they become heavier and can sink. Eventually, time, saltwater, and sunlight break it down from its recognizable, everyday forms—combs, candy bar wrappers, CD cases—into fragments so tiny that even thousands of them together can’t be seen by a naked eye trained on a calm sea.

And as far as it has traveled, the plastic in the garbage patch still has a long way to go. It will take decades, maybe even centuries, for those fingernail-sized fragments to degrade into smaller particles. And even then, they will not cease to pollute. In one study of the North Pacific Gyre, virtually all water samples, even those that were free of plastic debris, contained traces of polystyrene, a common plastic used in a wide range of consumer goods.