When it comes to managing waste, the best solutions mimic nature.

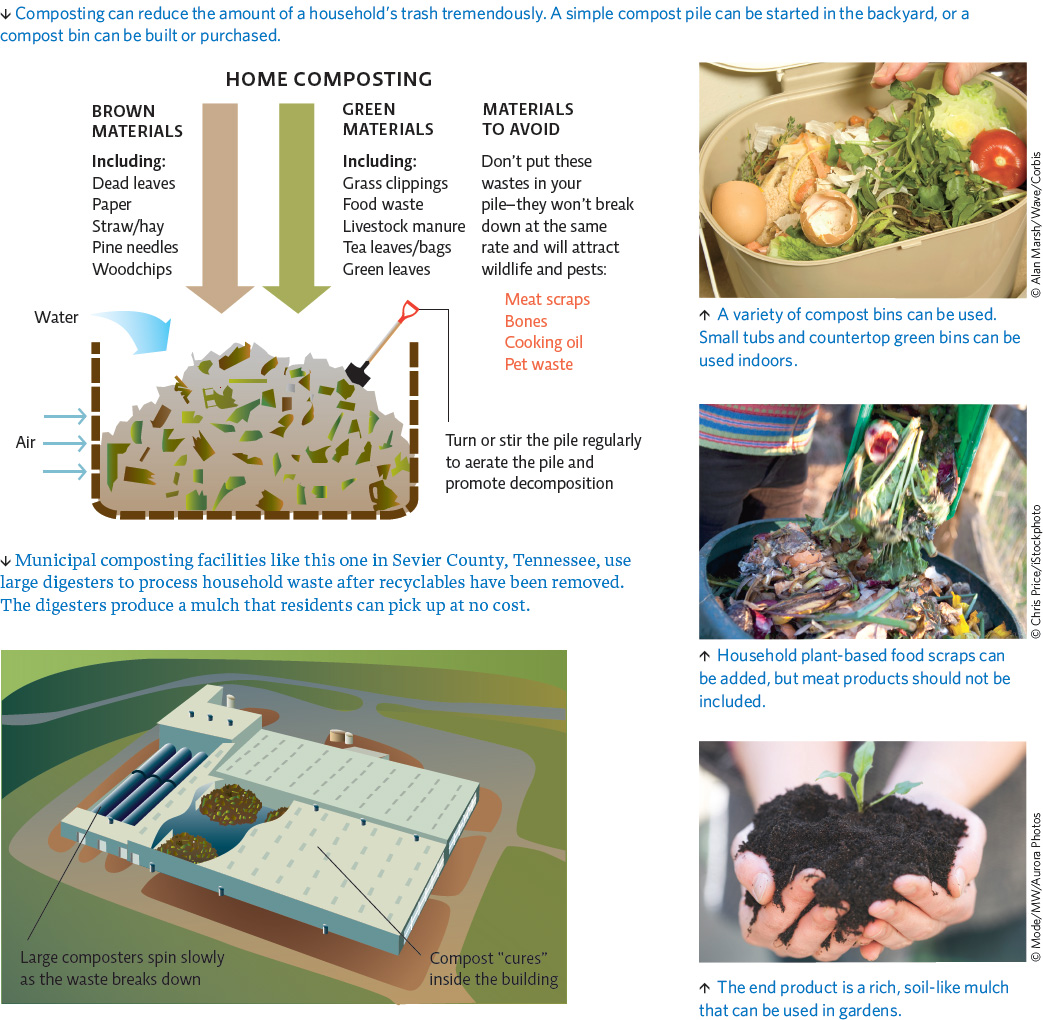

While nondegradable trash like plastics presents a challenge for disposal, much of our waste is biodegradable, and we can apply the concept of biomimicry—emulating nature—to better deal with this part of our waste stream. Composting—allowing waste to biologically decompose in the presence of oxygen and water—can turn some forms of trash into a soil-like mulch that nourishes the soil and can be used for gardening and landscaping. Composting can be done on a small scale (in homes, schools, and small offices) or on a large one (in municipal “digesters”). But this works only for organic waste, such as paper, kitchen scraps, and yard debris. INFOGRAPHIC 7.6

composting

Allowing waste to biologically decompose in the presence of oxygen and water, producing a soil-like mulch.

© Alan Marsh/Wave/Corbis

© Chris Price/iStockphoto

© Mode/MW/Aurora Photos

Does your school cafeteria have a composting program? If not, what would it take to implement one?

Answers will vary - most will not have a program. Implementation of one would require a collection protocol, a place for the compost site, someone or group to manage the site and some use for the final product. The program could start small and grow over time. Consulting with other schools with composting programs would be a good starting place.

Another promising solution to some of our waste woes involves converting garbage or its by-products into usable energy. As mentioned before, the heat produced during incineration might be converted into steam energy or electricity. And the methane produced during landfill anaerobic decomposition can also be harnessed as an energy source. Engineers and scientists are working out ways to use methane-producing microorganisms to process trash in vats or digesters.

KEY CONCEPT 7.6

Composting organic trash is a waste disposal method that mimics nature: It allows waste to decompose and produces a mulchlike product that can be used to return nutrients to soil.

In fact, the concept of spinning waste into energy that could then heat or light our homes or fuel our cars is so appealing that it has even extended to waste found in the open ocean. Not long after the Atlantic and Pacific patches were found, a San Francisco— based environmental group tried devising ways to turn the plastic bits into diesel fuel. That plan proved impossible. “There is no way to remove all those millions of tiny pieces without also filtering out all the millions of tiny creatures that inhabit the same ecosystem,” says Kara Law. “So once it’s out there, all we can really do is hope that nature eventually breaks it all the way down.” That could take hundreds to thousands of years. In the meantime, she says, we need to stop adding to the patches that already exist.