The loss of the wolf emphasized the importance of an ecosystem’s top predator

Thanks in part to Smith’s determination, the Yellowstone Gray Wolf Restoration project is going strong. There are approximately 80 wolves in Yellowstone National Park (and more than 5,000 living in the lower 48 states). But one chief lesson hammered home by observing wolves in Yellowstone is that populations do not exist in isolation. “Work in central Yellowstone clearly demonstrated that the addition of a keystone species, such as wolves, can result in observable changes in the behavior of its prey,” says Claire Gower, a wildlife biologist at Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. “These consequences may not stop at the prey individual, but may have cascading effects on other community-level processes.”

After wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone, project scientists documented that coyote populations in the area shrank, in part because the wolves were killing them, usually when the coyotes would approach a fresh wolf kill. Coyotes, which were running in packs in Yellowstone before the reintroduction of the wolf (unusual for coyotes), have begun reverting to traveling in pairs, more common for this species. Wolf reintroduction also indirectly impacted grizzly bear diets. The foraging of elk on berry bushes declined significantly, allowing these bushes to produce more summer fruit. Grizzly bear consumption of berries increased 20 and 2 fold in July and August, respectively, when compared to berry consumption before wolves were reintroduced (1968–1987). The increased consumption of this late summer food source may be especially important for breeding females.

KEY CONCEPT 9.8

Population size is influenced by top-down and bottom-up factors, but which one exerts the greatest effect varies from population to population.

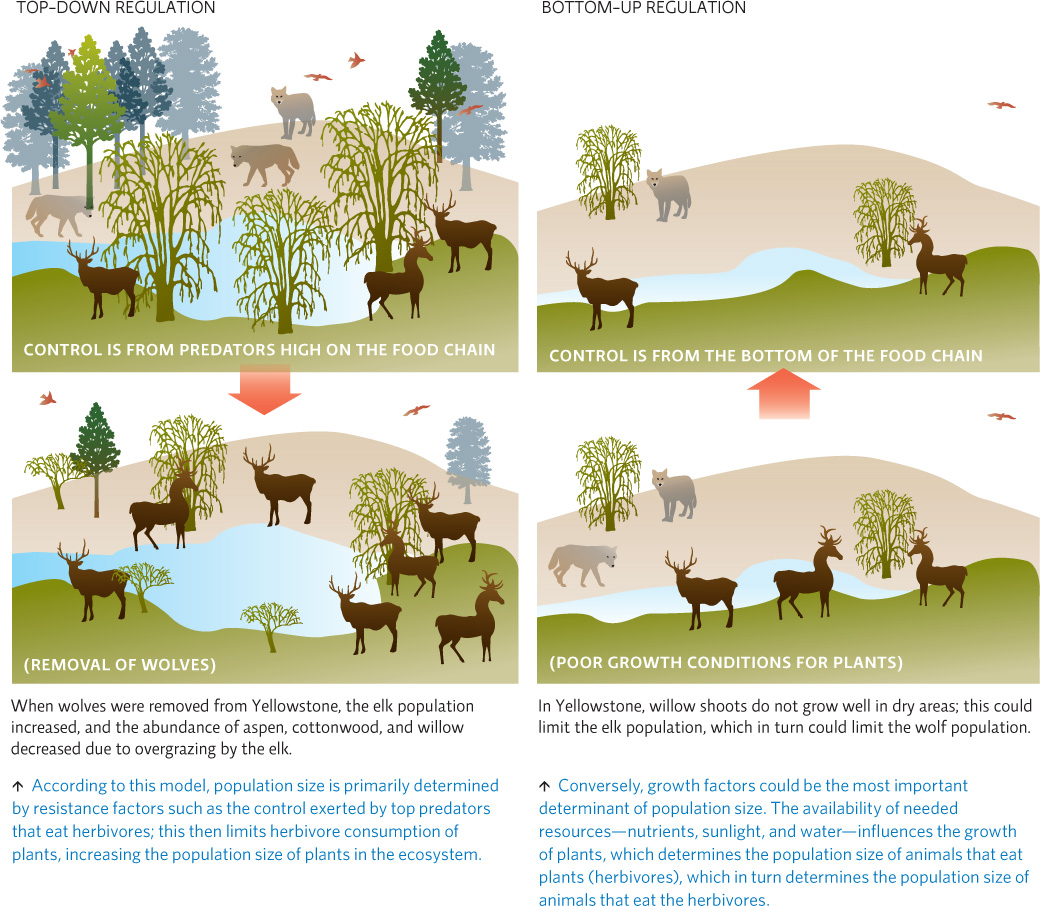

Elk populations dropped after the wolf introduction. The ability of a predator (or other resistance factor) to control the size of its prey populations is known as top-down regulation. However, ecologists have debated for years the relative importance of top-down regulation versus the regulation by growth factors that boost numbers such as the availability of water and food or sunlight (bottom-up regulation). The lynx—hare relationship shown in Infographic 9.6 is an example of top-down regulation because, according to studies, hare populations are determined by predation pressures rather than food availability. Even physical disturbances like fire are considered bottom-up regulators when they free up nutrients, boosting plant growth. In Yellowstone, the picture that seems to be emerging is that both top-down and bottom-up regulation are important in controlling elk populations and the plant species on which they feed. Which is most important in a given place and time, or for a given or species, varies. Determining whether the return of the wolf has provided meaningful top-down regulation is turning out to not be as easy as researchers once expected it to be. INFOGRAPHIC 9.7

top-down regulation

The control of population size by factors that reduce population size (resistance factors) such as predation, competition, or disease.

bottom-up regulation

The control of population size by factors that enhance growth and survival (growth factors) such as nutrients, water, sunlight, and habitat.

Population size is affected by both the presence of resistance factors (things that reduce population size) and growth factors (the availability of resources that allow the population to grow), but ecologists have long debated which one has the greatest influence on population size. In most cases, both impact population size, though which plays the greater role may vary from species to species or even within a species, depending on a wide variety of factors, such as relative population sizes of a population versus its predators, competitors or prey, or seasonal climate changes.

In most unprotected areas of the United States, wolf population densities are much lower than they are inside the protected Yellowstone National Park. Do you think wolves exert top-down control on elk populations in these unprotected areas? Explain.

Wolves probably do not exert top-down control in areas like these where their numbers are so low. Elk population control would be bottom-up (food supply driven) or top-down if hunting pressure was significant or if a disease were to move through and cause significant deaths.

For example, after the extirpation (local extinction) of the wolf and the increase of the elk population that followed, willow and aspen trees were overgrazed. Elk like to eat the tender young shoots, but they removed an important resource for other animals like birds (habitat) and beaver (food and building material) and also made it difficult for the new trees to grow and become part of the mature stand of trees. The decline of the beaver population was especially significant because beaver dams change the flow of water, creating lakes that support a wide variety of fish, amphibian, and plant species that would not frequent the faster-flowing stream. The loss of these dams allowed streams to return to their original flow, changing the community that lived in the area.

“Work in central Yellowstone clearly demonstrated that the addition of a keystone species, such as wolves, can result in observable changes in the behavior of its prey.” —Claire Gower.

After the wolves’ return to Yellowstone, willow stands appear to be recovering in some areas. In others, the ecological changes that resulted from the earlier overgrazing are proving difficult to overcome. A study by Kristen Marshall, then at Colorado State University, showed that even in areas where elk are physically blocked by fencing, willows are not growing tall enough to be useful to beaver unless simulated beaver dams (flooded areas) are included in the area. Increased feeding by elk over time contributed to changes in the ability of the soil to hold water; without vegetation to prevent soil erosion, less water is in the soil and available to plants. If the willows cannot grow tall enough to lure back beaver (due to the very lack of beaver dams), these streamside ecosystems may not return to their former configuration, even with fewer elk. An altered ecosystem may yet emerge in these areas.

Aspen are also regrowing in some areas but not all. Elk are less likely to browse in aspen groves if wolves are in the area, but wolf presence does not always lead to aspen recovery. Oregon State University researcher Cristina Eisenberg discovered that in areas where there are lots of wolves, elk returned to feeding on aspen. She surmised that when predation pressure is predictable and high everywhere (field, forest, and aspen groves), elk returned to feeding on their preferred food. Eisenberg found that aspen recovery was only seen in areas of high wolf population density where wildfire had swept through. Wildfires clear out competing plants (including adult aspen trees), spurring a burst of growth of young aspens. Fire that leaves behind fallen trees creates a habitat that elk generally stay away from (escaping the wolves would be difficult in these deadfall littered areas). Without elk present, young aspen shoots in these areas grow tall enough to escape elk browsing when the elk eventually return, allowing the aspen stand to recover.

As with any complex system, it is proving difficult to tease apart the impacts of several contributing factors on elk, aspen, and willow populations. Are wolves facilitating a recovery of these trees by reducing elk populations and reducing the amount of time elk spend foraging on these plants? As Eisenberg puts in her book The Carnivore’s Way, the answer seems to be “It depends.” It depends on the size of the given elk population and the abundance of food; it depends on climate and season; it depends on fire and drought; it depends on wolf populations and perhaps other, as-yet-unidentified factors.

The overall effects of returning wolves to Yellowstone is just beginning to unfold and be uncovered by researchers. The fact that the wolves were removed for so long may have changed the ecosystem for good. This is reason to pause and consider human actions today that threaten other species. Many populations of animals other than wolves are declining worldwide due to human impact, especially from habitat loss, the introduction of non-native species, and predator removals. In fact, the number-one reason that species become endangered today is habitat destruction (see Chapter 13). People damage habitats, remove resources, and break needed connections within ecosystems, and populations respond: Some species may benefit from the change and their population could increase (spotted knapweed, a non-native plant in Yellowstone, spreads quickly in disturbed areas), while other species may decline in number because they are displaced by others or because needed conditions for growth are no longer present. (Songbirds may lose habitat if the woodland patches they nest in are cut down.) Understanding community interactions and population dynamics helps managers monitor, protect, and restore populations.

The success of the reintroduction program has led to the wolf being “delisted” in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming (a delisted species is no longer protected by the ESA; management authority is returned to the state), though not without opposition from some conservation groups. This delisting has allowed wolf hunts with quotas set by the Fish and Wildlife Service. To Smith, the management of wolves includes the protection of some packs but policies that allow hunting of others. He reasons that hunting wolves only in areas where they conflict with humans may be one of the best ways to protect wolves in wild places like Yellowstone. If people know they can protect their animals and livelihoods, they may be more amenable to allowing the wolves to remain in wilderness areas.

To ensure that the wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone are given a chance to really flourish, Smith and his colleagues diligently stay on the wolves’ trail, studying their population dynamics. “We want to know their population size, what they are eating, where they are denning, how many pups they have and how many survive, and how the wolves interact with each other,” he explains. Why is it so important to ensure that the wolves do well? Simply put: They were here first, he says. “We want to restore the original inhabitants to the Park.”

Select References:

Beschta, R. L., & W. J. Ripple. (2014). Divergent patterns of riparian cottonwood recovery after the return of wolves in Yellowstone, USA. Ecohydrology. doi: 10.1002/eco.1487.

Eisenberg, C., et al. (2013). Wolf, elk, and aspen food web relationships: Context and complexity. Forest Ecology and Management, 299: 70–80.

Krebs, C. J. (2011). Of lemmings and snowshoe hares: The ecology of northern Canada. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 278(1705): 481–489.

Marshall, K. N., et al. (2013). Stream hydrology limits recovery of riparian ecosystems after wolf reintroduction. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1756): 20122977.

Ripple, W. J., et al. (2014). Trophic cascades from wolves to grizzly bears in Yellowstone. Journal of Animal Ecology, 83(1): 223-233.

Smith, D., et al. (2013). Yellowstone Wolf Project: Annual Report, 2012. Yellowstone National Park, WY: National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources.

PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

Understanding the factors that influence how populations change can help us manage species that are facing extinction or help us control (or even eliminate) non-native species that are causing problems. How people view species and their connection to our world has a large impact on how management plays out.

Individual Steps

•Learn more about wolves at the International Wolf Center (www.wolf.org).

•Use the Internet and books on wildlife to research what your area might have been like prior to human settlement. Which species have been extirpated, and which ones have been introduced? How have wildlife populations changed as a result of human action?

•See if you can recognize distribution patterns in the wild. Do some flowers or trees grow in clumps or patches? Can you find species that appear to have a random or uniform distribution?

Group Action

•Explore organizations that support predator preservation, such as Defenders of Wildlife and Keystone Conservation, for suggestions on how you can help educate others about the importance of predators.

•Join a local, regional, or national group that works to monitor, protect, and restore wildlife habitats, such as the Defenders of Wildlife Volunteer Corps.

•Investigate predator compensation funds such as the Defenders of Wildlife Wolf Compensation Trust and the Maasailand Preservation Trust (for livestock losses due to lion predation). Do you feel this is a worthwhile approach?

Policy Change

•Check the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service website, www.fws.gov, for updates on wolf management and protection status.

•Write a letter to the editor of your newspaper in support of or in opposition to the decision to delist the wolf in parts of the American West.

John E. Marriott/All Canada Photos/Getty Images