14.2 Humans rely on protein from fish.

Simply put: humans need fish. We consume more seafood every year than we do beef, pork, and chicken combined. In fact, over 15% of the world’s population relies on fish as their main source of protein. In poorer nations, this preference is driven by the cheaper cost of fish compared with meat and poultry. In wealthier nations like Canada, a preference for seafood emerged as scientists uncovered an array of health benefits associated with the omega-3 fatty acids found in fish oils—especially the fish oils of cold saltwater species. In recent decades, a bevy of trendy diets have been built around fish consumption. Canada’s Food Guide recommends that Canadians eat at least two servings of fish per week.

It’s not just fish protein we have come to rely on. More than 200 million people around the world earn their living in the fishing industry, which generates some $130 billion annually in global revenue. Developing countries are especially dependent on fish, not only as a source of protein, but also as a source of revenue. More than half of all fish sold in the global market comes from developing countries, and fish make up the single biggest developing country export.

With the coalescence of new technology, rising demand, and multiple fishing nations, the once-prolific Grand Banks Atlantic cod fishery was decimated.

But for all the health and economic benefits this massive industry provides, it has also exacted huge—some would say catastrophic—environmental costs.

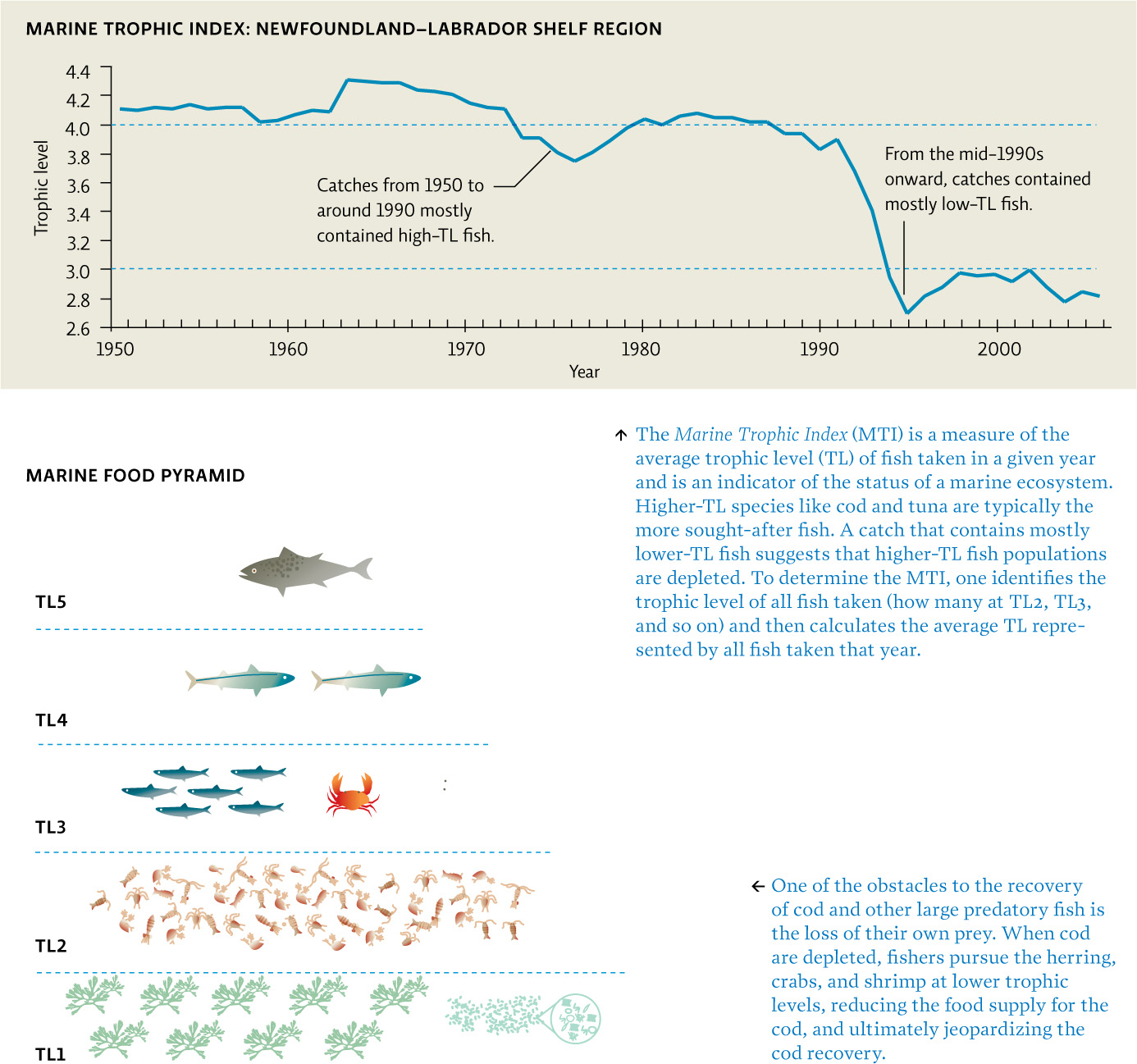

Declining fish populations can impact an entire ecosystem, especially one with a simple food web comprised of few species, like that of the cold waters of the North Atlantic.

248

Unbalanced food webs could irreversibly change the ocean ecosystem of the Grand Banks cod. Loss of apex predators often disrupts food chains by allowing lower-trophic-level species to increase in number. For example, declines in cod and the fish they feed on have led to an increase in populations of small jellyfish-like organisms called hydroids. Hydroids make it harder for the cod population to recover, by feeding on the same food as the very young cod and on the juvenile cod themselves. [infographic 14.3]

Overfishing of upper-trophic-level fish has led humans to continually seek out new species to harvest, at lower and lower trophic levels; this is called “fishing down the food chain.” Interestingly, fish lower on the food chain are seen as less desirable for human consumption. Some vendors get around this by renaming the fish once it gets to market. For example, there is not much of a market for the invasive Asian carp that is causing problems in North American waters, but marketers here have plans to bring it to market as “Silverfin.”

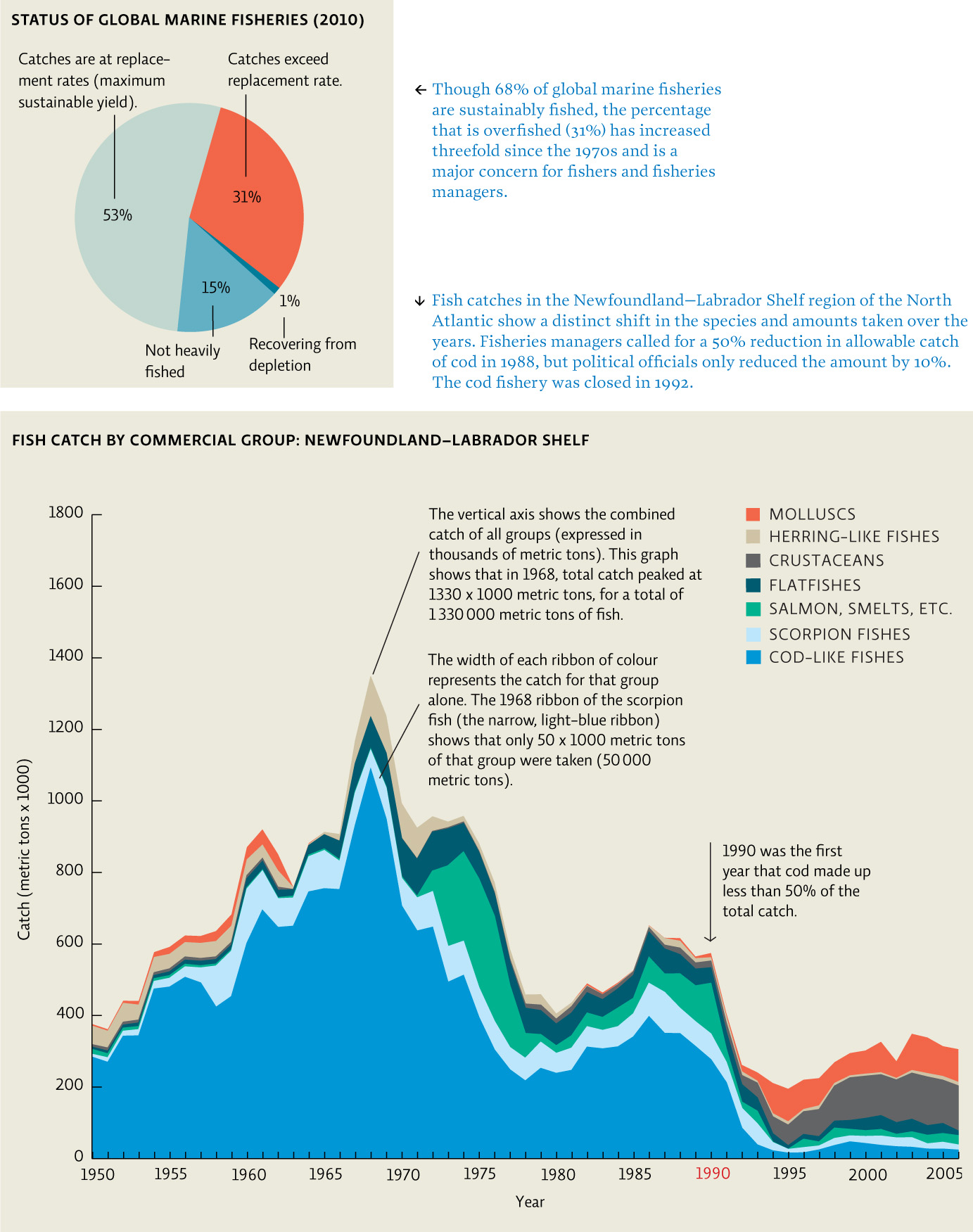

Today, the oceans—not to mention the fish themselves—are in grave danger. The number of large fish like tuna, cod, and halibut in the ocean is only 10% of what it was in 1950. Over half of the world’s fisheries are fully exploited and at their maximum sustainable yield (the amount that can be harvested without decreasing the yield in future years). Another 32% are overexploited fisheries, meaning they are being harvested at an unsustainable level, or depleted fisheries, meaning that the population size is very low compared to historic levels and there are not enough fish left to support a fishery. Unless we change our ways, scientists predict that all commercially valuable wild fish populations may collapse by the middle of the century. [infographic 14.4]