18.3 Some industrial agricultural practices have significant drawbacks.

By presenting an alternative way to grow both rice crops and duck meat, Furuno’s methods confront two of the Green Revolution’s biggest legacies: monoculture crop production, and concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) for livestock.

In monoculture farming, a single variety (genetically identical individuals) of a single crop (rice or corn or soybeans, for example) is planted over huge swaths of land. The uniform crops of a monoculture are easier to plant, maintain, and mechanically harvest. This makes mass production easier, which in turn makes for a more bountiful harvest.

In a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO), livestock are raised in confined spaces, with a focus on raising as many animals in a given area as possible. They are fed a nutrient-rich diet of grain and soybean (in the case of cattle, this diet is supplemented with some hay) and are generally not permitted to graze or roam free. CAFOs are highly productive; they minimize the amount of land that is used; and because animals are so concentrated and confined, it is easy to harvest the animals’ manure and sell it as fertilizer. Since about the mid-1900s, high-density feedlot operations like this have been the most common method of raising cattle in Canada and the United States. Today, poultry (chickens and ducks) and pigs are also predominantly raised in CAFOs.

But for all their benefits in efficiency and production volume, monocultures and CAFOs present a number of disadvantages.

For starters, both monocrop agriculture and CAFOs contribute heavily to global warming. Clearing so much land to grow food reduces the amount of carbon that can be sequestered by natural vegetation through photosynthesis. Also, fertilizer and livestock emit greenhouse gases. In fact, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, livestock is responsible for some 18% of anthropogenic greenhouse gases.

In monocrop agriculture, the crop that is chosen is not necessarily locally adapted. Instead of focusing on which crop is best suited to the existing ecosystem, farmers focus on those crops with the highest market demand, and thus the highest dollar value. This shift, combined with the exponentially higher volume of plants, has made most farms heavily dependent on external inputs—water, pesticides, and fertilizer—that are added to the farm from outside its own ecosystem. “In the 1920s, half of Iowa’s farms produced 10 commodities each,” says Fred Kirshenmann, a distinguished fellow at Iowa State University’s Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture. “Today, 80% of the state’s cultivated land is exclusively corn or soybean. Farming systems that were once supported by complexity and diversity of species have now been replaced by reliance on inputs.”

322

This dependence makes monocrop agriculture both expensive and environmentally taxing. Heavy farm machinery compacts soil and increases its erosion. Use of irrigation can result in soil salinization; as water evaporates from the soil, salts are left behind and become so concentrated that crops can no longer grow.

CAFOs come with their own set of problems: they are environmentally taxing and ethically questionable. While the high grain diets fed to confined animals certainly maximize growth, they are not necessarily good for the animals’ health. Such diets may cause liver and stomach disorders, increased susceptibility to infections, and even death. In addition, crowded living conditions (viewed by some as inhumane) make CAFO animals more vulnerable to disease, forcing farmers to use heavy doses of antibiotics to prevent sickness. Such heavy use contributes to antibiotic resistance, which threatens the health of the animals and humans. Resistant microbes that develop in the livestock can make their way into the water supply and spread to other food sources. They can also be passed directly to consumers in the meat itself.

323

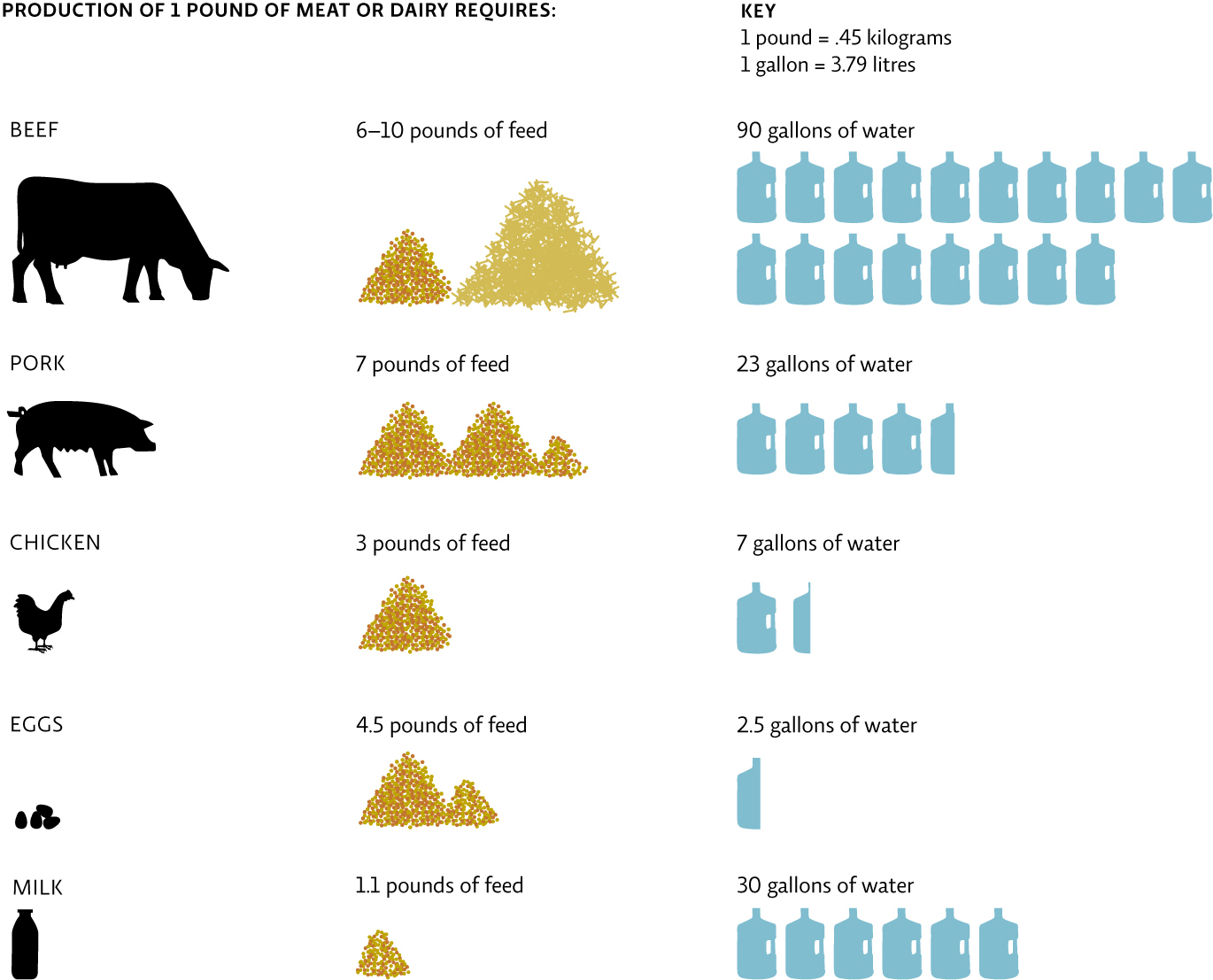

CAFOs have drawn the ire of environmentalists who point out that the grain and soybean used to feed all those livestock would feed far more humans than the meat we harvest from the animals actually does. The reason for this has to do with feed conversion rates—how quickly and efficiently any given animal converts the food it eats into body mass (that we then eat). Cattle have a high food conversion rate, meaning it takes a lot of feed to produce a litre of milk and even more to produce a kilogram of meat. It also takes a lot of resources (namely, water and fossil fuel) to produce that feed. Chickens and pigs have slightly better feed conversion rates and thus require slightly fewer resources to grow, but not by much. [infographic 18.4]

In Canada and the United States, a niche market has developed for “grass-fed” beef, which is produced from animals that are raised on pasturelands as opposed to CAFOs. Grass-fed animals don’t gain weight nearly as rapidly as feedlot animals do; they eat less and spend more time moving around, so they don’t get quite as fat. But the meat and milk they produce is healthier—it has less saturated fat and more omega-3 fatty acids than CAFO-generated beef. And the animals themselves live better lives—rather than being confined in a tight space, they are free to roam the grasslands and eat the food (namely grass) that they have evolved to process and digest. In fact, unlike CAFO livestock, grass-fed animals can represent a net gain for the human food supply when grazed on land that is unsuitable for human crops; they eat grasses that we can’t eat, and turn it into beef and dairy products that we can eat (see Chapter 12).

The ducks on Furuno’s farm are like the grass-fed cattle: they are raised in a humane environment, without any undue environmental costs. But whether or not his methods would work as well on the other side of the planet was an open question.