18.4 Sustainable agriculture techniques can keep farm productivity high.

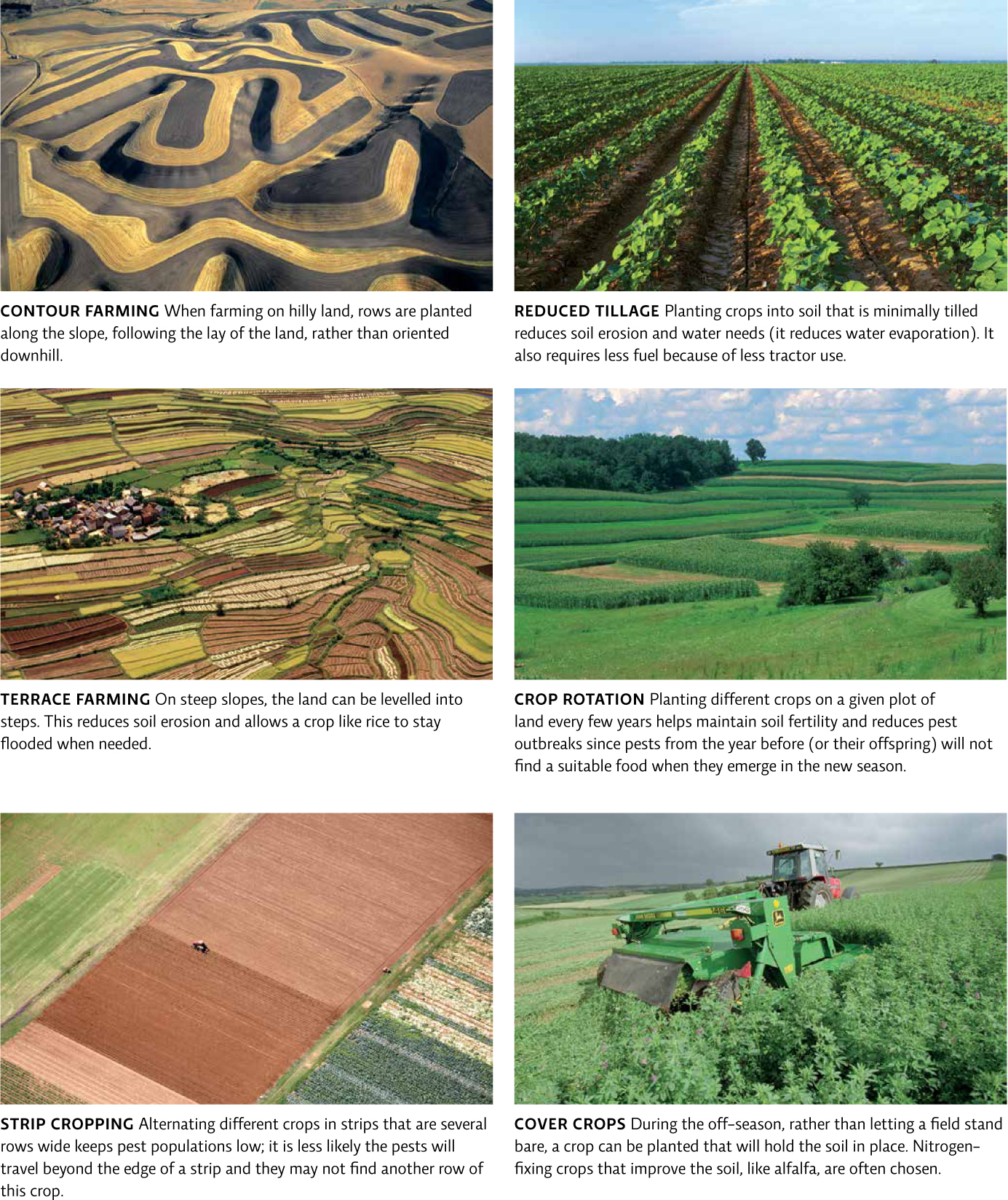

Greg and Raquel were well versed in the problems of modern agriculture. Before settling in California to take over the family farm, they had worked as tropical ecologists in Costa Rica, where they learned about traditional, non-industrial farming methods such as terracing, crop rotation, and strip cropping that help protect the soil and keep productivity high without the use of synthetic fertilizers. [infographic 18.5]

324

325

In rice farming, they saw a chance to implement all the concepts and theories they had learned as ecology students, and refined and discussed as scientists, on their own land. “We wanted a farm where success was measured not just in crop yield, but in the overall health of the land,” Greg says. “A place where we would count profits, but we would also count the number of Sandhill cranes and California quail we saw populating the area.”

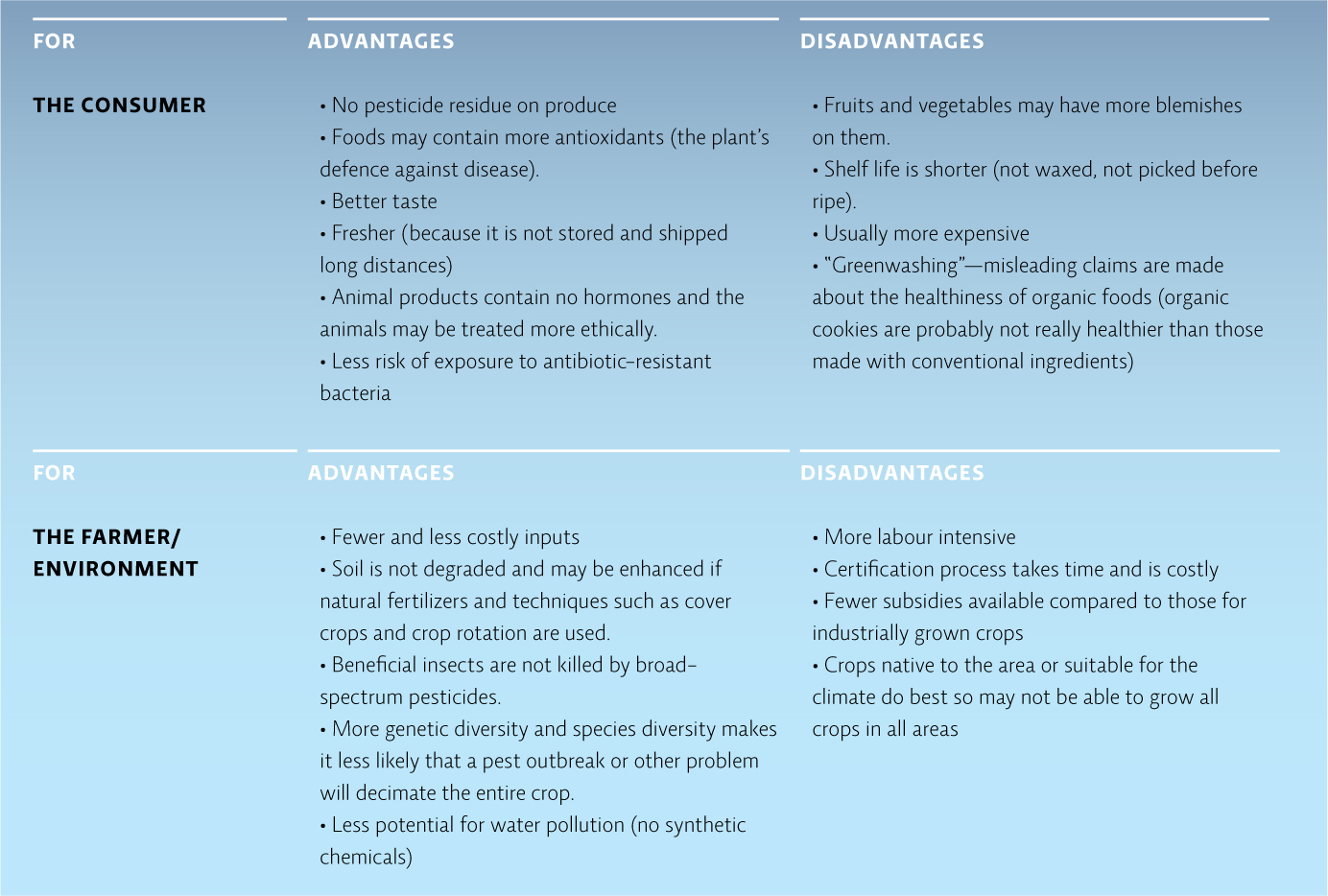

They wanted to create a farm that was sustainable and at least partly local (they planned to sell a portion of their rice at local outlets like farmers’ markets and food co-ops). Sustainable agriculture means depending on farming methods that can be used indefinitely. In addition to looking for sustainably or organically produced food, many consumers are buying food from local farmers; local agriculture supports local economies, provides fresher and thus healthier food to consumers, and minimizes the ecological footprint because food has been shipped over much smaller distances. Of course, sustainable and organic agriculture have their own set of trade-offs: while they might be more environmentally friendly, they are also more expensive and in some cases produce less food per hectare of land. But Greg and Raquel were determined to at least try. [infographic 18.6]

To achieve their goals, the Massas began by installing a recirculation system to reclaim and reuse irrigation water. They planted native oak trees along field borders to serve as a natural windbreak (windbreaks prevent soil from being carried away by wind erosion), and installed nest boxes for wood ducks, barn owls, and bats so that those wild animals would keep area pests in check. “The idea was to restore as much of the natural biodiversity as possible,” says Greg, “so that we would not need artificial inputs to run the system.” They also took their sustainable ideals to the next level and built a straw house to live in—made of 0.6 metre-thick walls of rice bale, coated on both sides with plastic or stucco—that can withstand the unforgiving heat of a Chico summer and maintains a steady temperature almost entirely by itself. The house is fire proof, rodent proof, and as Greg likes to joke, bullet proof, too.

326

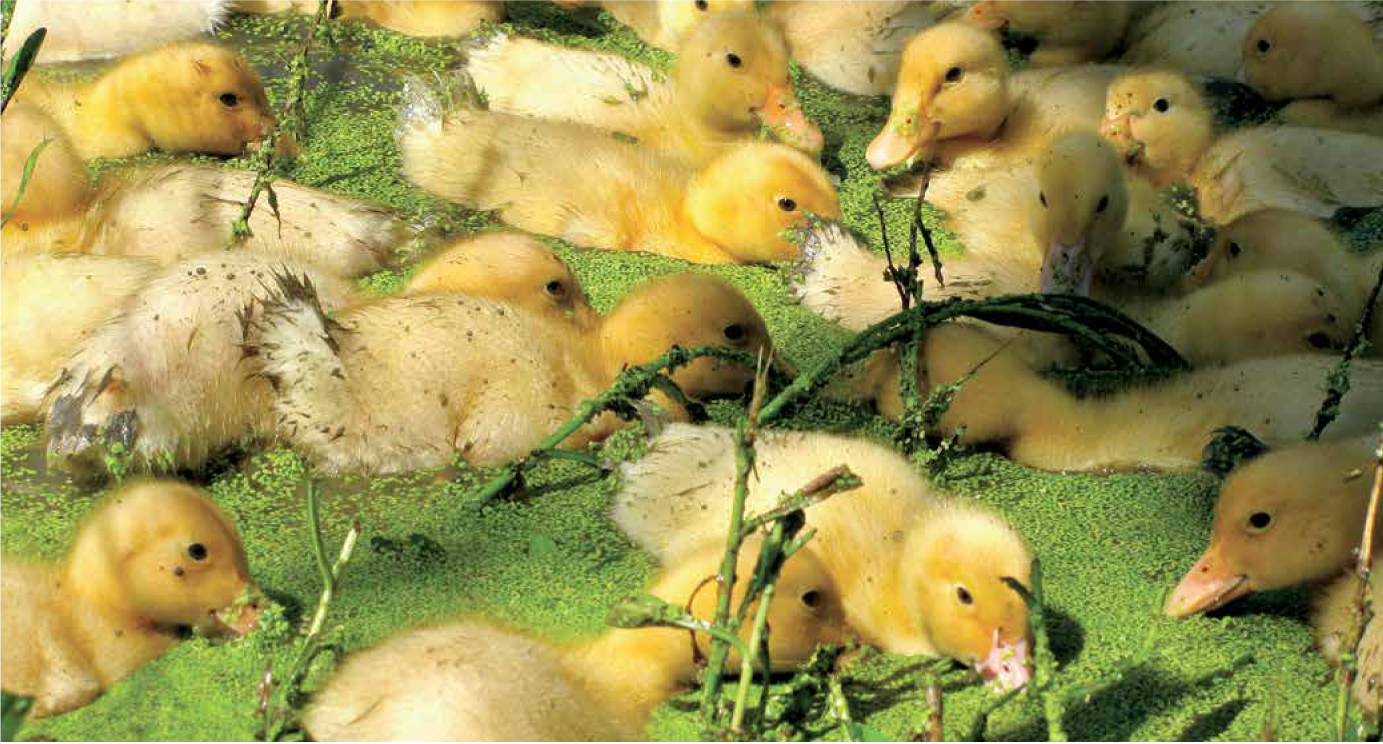

Furuno’s method of duck/rice farming would be a good fit for the Massas. Not only would the rice plants rely on natural fertilizers and natural pest control, but the duck eggs and meat produced would be more humanely grown than those produced by factory farms. The ducks would grow up in ponds, not crammed together on slats in a barn with no access to swimming water. They would get to splash around, and express their “duckiness,” as Raquel put it.

When the ducks first arrived on the Massa farm, they were just 24-hours-old, cotton ball-sized tufts of yellow feathers. The Massa children cared for them in wooden crates in their barn. But as Raquel soon learned, small ducklings grow mighty fast. In just 2 weeks, they were large enough to turn loose. Furuno had advised stocking about 100 ducks per acre (4047 square metres), but Greg and Raquel did not want to sacrifice that much land for this first attempt, so they fenced off just a quarter-acre (1012 square metres), instead. This amount of space provided plenty of room for their 120 ducks to swim and forage in, but as it turned out, not enough food to support them. “They quickly ate all the weeds in the field,” says Greg. They also trampled some of the rice plants in their pond because their section of field was too small. But, even as they ran out of weeds to eat, the baby ducks stayed away from the rice plants. Just as Furuno had insisted they would.