18.5 Genetically modified crops may help feed the world.

Though promising, methods like the ones Furuno and the Massas are implementing represent only part of the solution to our emerging food problems. Critics say that by itself, organic farming will never produce as much food as industrial agriculture has, and neither organic nor current industrial practices will be enough to feed 10 billion people. So as population swells, scientists are working on another solution, one that has given rise to its own debates and controversies: genetic engineering.

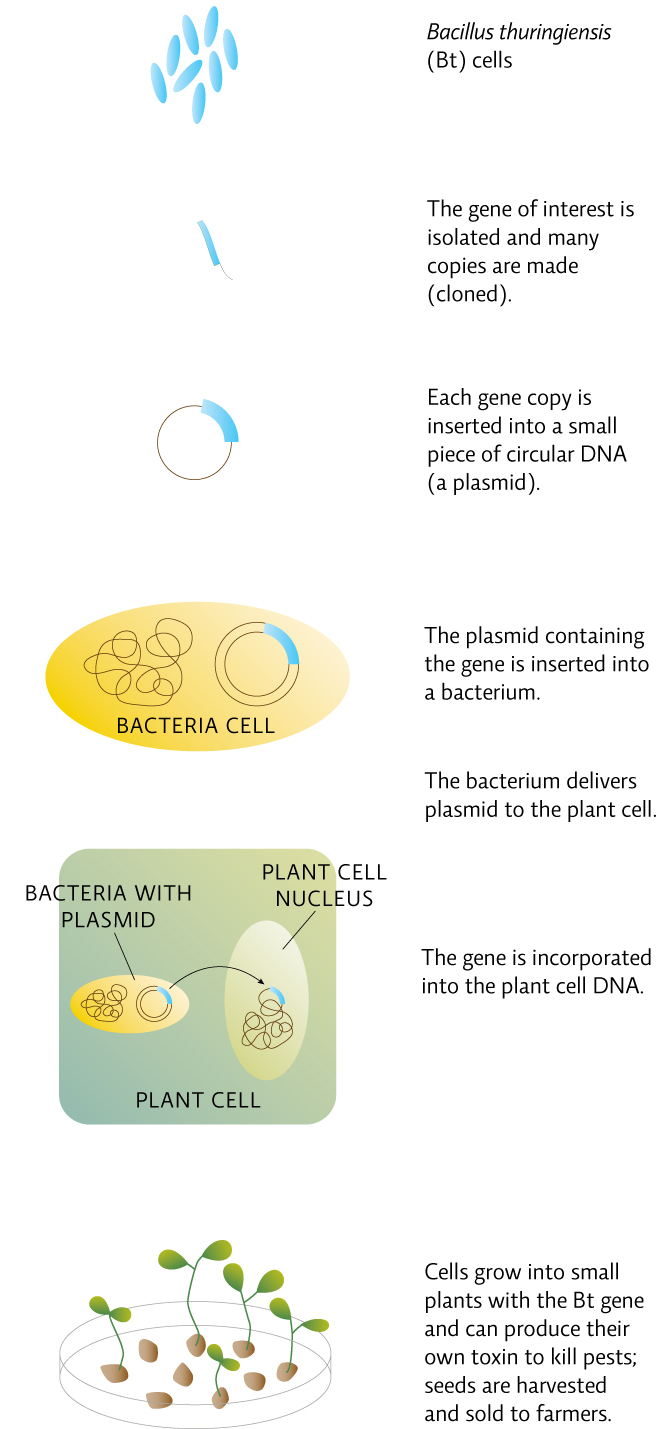

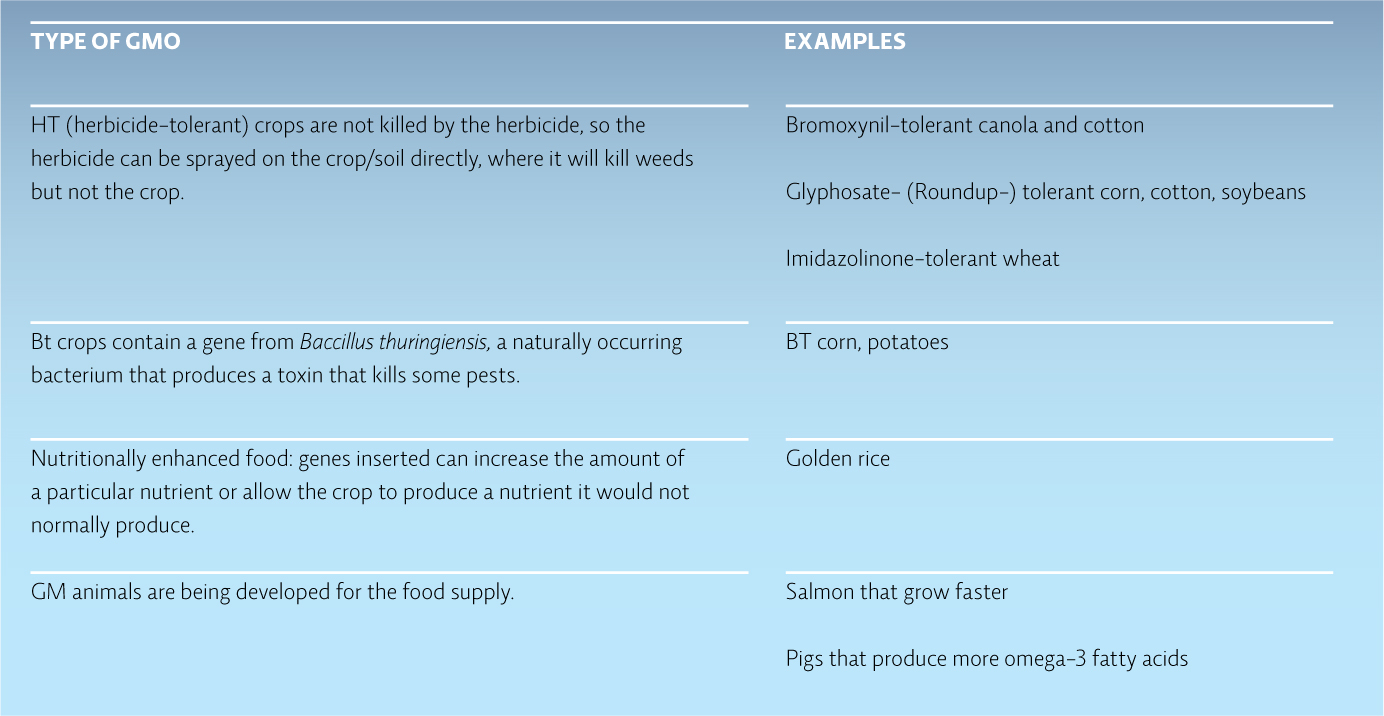

Genetic engineering forms the basis for what some farmers and scientists like to think of as the Green Revolution 2.0; it involves manipulating genes to increase productivity or to make it possible to grow crops in places they normally wouldn’t—like marginal land, in drought-plagued regions, or on fields doused in pesticide and herbicide. Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are organisms that have had their genetic information modified in a way that does not occur naturally. This usually involves transferring new genes for desirable characteristics—such as pest resistance, drought resistance, or increased nutrient production—from one species to another, creating a transgenic organism. [infographic 18.7]

327

Most existing GMO crops are altered to have greater pest resistance (for example, Bt transgenic plants), but scientists are also working on drought-tolerant varieties of plants and have had some success in creating nutritionally enhanced food. The most notable example is golden rice, which was genetically modified to produce extra beta carotene. Deficiencies of beta carotene, which produces vitamin A, is a leading cause of blindness in children.

In Canada, more than 70% of food sold contains GMOs, mainly corn, canola, and soybeans. Most of these crops have an herbicide-tolerant (Ht) gene added so that they can withstand huge doses of herbicides. Scientists are also working to add genetically modified animals to our food supply. AquaBounty has developed a genetically modified Atlantic salmon that grows much faster than normal (thanks to genes from the larger Chinook salmon) and is currently seeking approval from the U.S Food and Drug Administration to bring the fish to market. If approved, this would be the first GMO animal food product sold in the United States. [infographic 18.8]

In other parts of the world, however, including China and the European Union, GMOs have been met with fierce opposition from consumers who worry about the long-term health impacts and environmental consequences.

One concern is that domestic crops with introduced genes could hybridize (crossbreed) with closely-related wild plants. If a pest-resistance gene became part of weed species genomes, those weeds could grow more aggressively and outcompete other plants, including crops. We already have many herbicide-resistant weeds in North America, though this does not appear to be the result of transfer of genes from GMO crops, but rather from adaptation to a high-pesticide environment. Over 200 weed species have already evolved a herbicide tolerance (Ht) gene globally. These so-called super weeds, including ragweed and pigweed, can be found in 5 provinces and can tolerate common herbicides such as glyphosate. They take over entire fields, stop combines, and are tough to clear by hand.

328

Another problem, say opponents, is that GMOs are patented and owned by a few multinational corporations, which makes them more expensive than traditional seeds, and thus a bad option for developing countries. Much of the hunger seen in the world today arises not from lack of food but from an inability of the disempowered to access it. Putting even more of our food supply under the control of a few multinationals could only make this worse.

In the Sacramento Valley, where the Massa farm is located and where virtually all of the U.S. rice crop is grown, farmers are split over the merits of genetic engineering. Some see the advantage of having crops that can better tolerate drought, floods, and disease. “The climate is changing,” says one of Greg’s neighbours. “We see drier seasons and more extreme weather than we ever have before. And eventually we will need some breed of rice that can endure those changes.” But others, including Greg Massa, say that growing genetically engineered rice anywhere, in any quantity, poses a threat to their farms and livelihoods.

Here’s why: in 2006, small amounts of experimental strains of genetically engineered rice crept into the U.S. food supply. Nobody knows how the strain, engineered by the company Bayer to be herbicide resistant, escaped from the Arkansas storage bins where it was being kept. However, when news spread, European retailers pulled all U.S. rice from their shelves, sending rice prices plummeting and threatening the sanctity of the Massa farm and all of its neighbours. “The problem is, even the threat of contamination can kill our businesses,” says Greg. “So it’s really a danger to grow it anywhere, at least until it wins wider approval. And in the meantime, there are other ways to combat weeds. The duck farming proves that.”

329

At any rate, GMOs are already here, and aren’t likely to disappear anytime soon. The bottom line: this technology will almost certainly help address some of our food issues, but as with all new technology, we will have to weigh risks and benefits very carefully with each step forward. And as the global population swells, we will probably need all solutions—crops that have been engineered to resist weeds, and crops grown in more integrated, natural systems, like the duck/rice farms of Japan and California—to feed the world.

For the Massas, duck/rice farming has proven to be the best possible solution to the challenges of modern agriculture. They ended up with duck meat to sell, and though they didn’t take any precise measurements of yields during their first trial run, their rice crops did not appear to suffer at all. “We learned a couple of things,” Raquel says. “The ducks trampled some of the rice in their pond, which would not have been a problem if we had used a larger section of the field. I also think we used the wrong breed of duck. They were a little too large to move effectively between the dense plants, and they were not active enough in their foraging abilities. These ducks were bred to sit around all day and eat and gain weight quickly for industrial meat production. We are currently researching which breeds to try next.”

Still, in the end, the Massas harvested both rice and duck meat. The key to successful duck/rice farming is to harvest the ducks before they get big enough to trample rice plants or strong enough to pluck rice seeds from deep within the mud. The hard part isn’t knowing when to do this, but having the resolve for what comes next: killing and eating the ducks. The Massa family struggled, but ultimately felt good about the outcome. “I know the conditions in which they were raised were more humane than 99% of the meat ducks in this country,” says Raquel. “They had it good and you can taste that in the finished product.”

Select references in this chapter:

Hossain, S.T., et al. 2005. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Development, 2: 79–86.

Reganold, J.P., et al. 2010. PLoS ONE, 5: e12346.doi:10.1371.

Russell, J.B., and Rychlik, J.L. 2001. Science, 292: 1119–1122.

BRING IT HOME: PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

Making food choices for your health and wellness, as well as for the vitality of the environment, requires some thought. Becoming an educated consumer is one way you can reduce your environmental impact, eat a nutrient-rich diet, and contribute to the public dialogue about the safety and sustainability of our food systems.

Individual Steps

Support local independent farms by shopping at farmers’ markets; buying a share in a community-supported agriculture (CSA) group in your area; and frequenting restaurants that serve food grown locally. For more information, visit the CSA website for your province.

Support local independent farms by shopping at farmers’ markets; buying a share in a community-supported agriculture (CSA) group in your area; and frequenting restaurants that serve food grown locally. For more information, visit the CSA website for your province.

Reduce the amount of animal products you eat and try to buy free-range and grass-fed meat whenever possible.

Reduce the amount of animal products you eat and try to buy free-range and grass-fed meat whenever possible.

Grow your own food. Transportation of food contributes heavily to emissions and fossil fuel usage; planting just a few edibles can greatly decrease your food footprint.

Grow your own food. Transportation of food contributes heavily to emissions and fossil fuel usage; planting just a few edibles can greatly decrease your food footprint.

Buy organic foods, especially for common produce that typically is heavily treated with chemicals, such as apples, celery, lettuce, strawberries, and peaches; this reduces the chemical residue you ingest and the chemicals released into the environment, and helps provide safer working conditions for people in the agriculture industry. Visit Canadian Organic Growers (www.cog.ca) to find a local organic farm near you.

Buy organic foods, especially for common produce that typically is heavily treated with chemicals, such as apples, celery, lettuce, strawberries, and peaches; this reduces the chemical residue you ingest and the chemicals released into the environment, and helps provide safer working conditions for people in the agriculture industry. Visit Canadian Organic Growers (www.cog.ca) to find a local organic farm near you.

Group Action

Find like-minded people to start a community garden in your area. Community gardens allow apartment dwellers to grow their own food in empty lots or in public spaces. Most are run by municipalities; look for information on your community’s website.

Find like-minded people to start a community garden in your area. Community gardens allow apartment dwellers to grow their own food in empty lots or in public spaces. Most are run by municipalities; look for information on your community’s website.

Policy Change

GMOs offer promise for feeding the world’s population, but like all technologies, pose some risks, both known and unknown. Write letters to your newspaper asking for coverage of this issue. Support policies that require the testing, labelling, and traceability of GMO products.

GMOs offer promise for feeding the world’s population, but like all technologies, pose some risks, both known and unknown. Write letters to your newspaper asking for coverage of this issue. Support policies that require the testing, labelling, and traceability of GMO products.

330