19.2 The world depends on coal for most of its electricity production.

Simply put, coal equals energy. Energy is defined as the capacity to do work; like all living things, we humans need it, in a biological sense, to survive. But we also need it to run our societies: to heat and cool our homes; operate our cell phones, lamps, and laptops; fuel our cars; and power our industries. Most of our energy comes from fossil fuels—nonrenewable carbon-based resources, namely coal, oil, and natural gas—that were formed over millions of years from the remains of dead organisms.

336

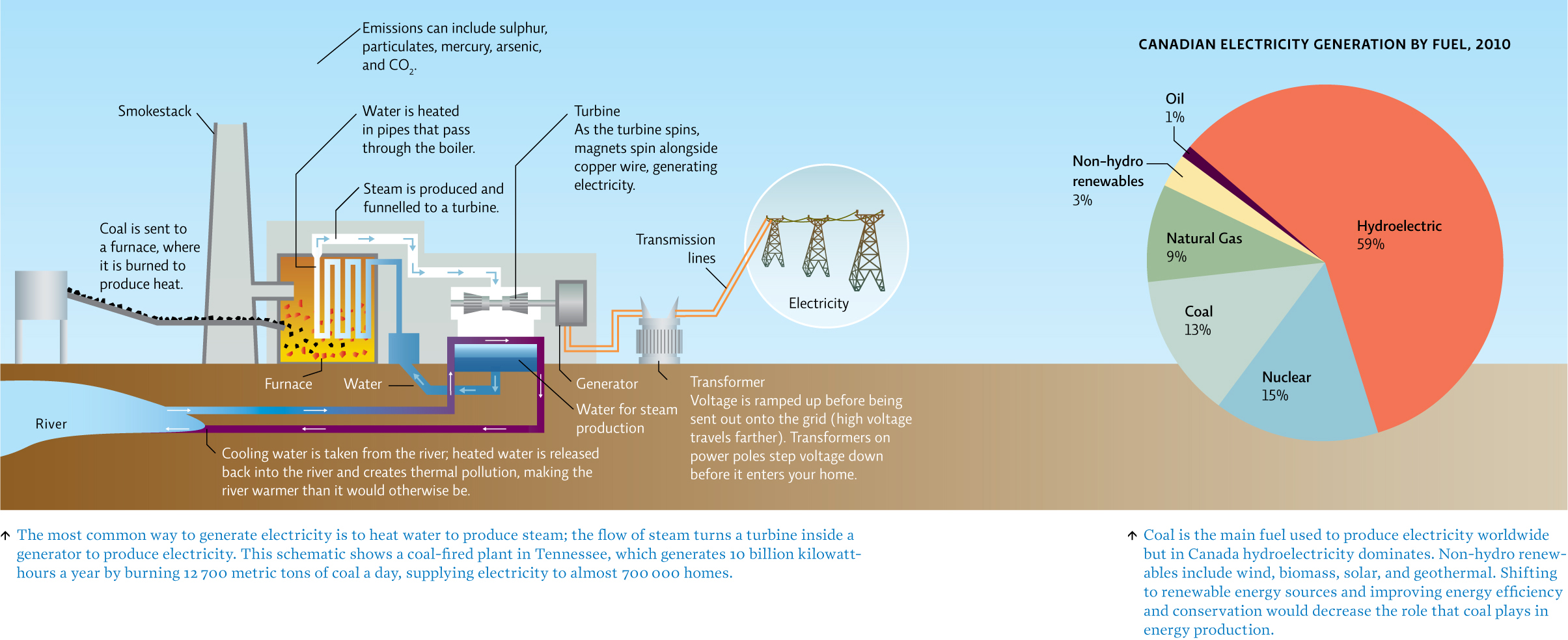

Canada consumes up to 60 million metric tons of coal annually, while the United States consumes almost 1 billion metric tons. Over 80% of this coal is used to produce electricity. The remainder is used to fuel cement, steel, and other industries. Electricity is a natural form of energy (lightning and nerve impulses are electrical) that we have learned to create on demand, producing it in a central location and sending it out via transmission lines. Burning coal produces over 40% of global electricity, 45% of electricity in the United States, and 13% in Canada (around 60% of Canadian electricity comes from hydropower).

Coal-fired power plants work by feeding pulverized coal into a furnace to generate heat, which then powers a system that produces electricity. It takes roughly 0.5 kilogram of coal to generate 1 kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity; that’s enough to run ten 100-watt incandescent light bulbs for an hour, an energy efficient refrigerator for 20 hours, or an older, less efficient one for 7 hours. The average U.S. family of four uses about 11 000 kWh of electricity per year. That comes out to some 5500 kilograms of coal, or 1375 kilograms per person.

So, how does coal stack up against other energy sources? On the one hand, it produces more air pollution than any other fossil fuel. On the other, it is safer to ship, cheaper to extract, and in the United States at least, more abundant by far. In fact, the United States has 10 times more coal than it does oil and natural gas combined; in 2010 alone, Americans mined almost 1 billion metric tons. Most of it came from Wyoming, which leads the nation as a coal producer, and the Appalachian mountains, which follow behind as a close second. While the United States exported some of that yield, the vast majority was used to power U.S. households and businesses. [infographic 19.1]

In terms of net energy, or energy return on energy investment (EROEI)—a metric that allows us to compare the amount of energy we get from any individual source to the amount we must expend to obtain, process, and ship it—coal is neither the best nor the worst. It has an EROEI of about 8:1 (8 units of energy produced for every 1 unit consumed for a net production of 7), compared to 15:1 for oil, 6:1 for nuclear, and 20:1 for wind.

337

There can be no denying the blessings of coal: this sticky black rock has powered several waves of industrialization—first in Great Britain and the United States, now in China—and in so doing has shaped and reshaped the world as we know it. But as time marches on, the costs of those blessings have become all too apparent: they include an ever-growing list of health impacts—from birth defects to black lung disease—and an equally lengthy roster of environmental costs—not only the destruction of Appalachia, but also the pollution of Earth’s atmosphere with CO2 and other greenhouse gases.

This litany of paradoxes has given rise to a deep national ambivalence in the United States. While U.S. residents are consuming more electricity, and burning more coal, than at any time in history, applications for new coal-fired power plants have been rejected left and right in recent years by determined citizens and local governments. “We’re caught in a catch-22,” says Scott Eggerud, a forest manager with West Virginia’s Department of Environmental Protection. “On one hand, it’s like we need the stuff to live; on the other hand, we see that it’s kind of killing us.” Nowhere is this catch-22 more pronounced than in the foothills of Central and Southern Appalachia.