19.4 Mining comes with a set of serious trade-offs.

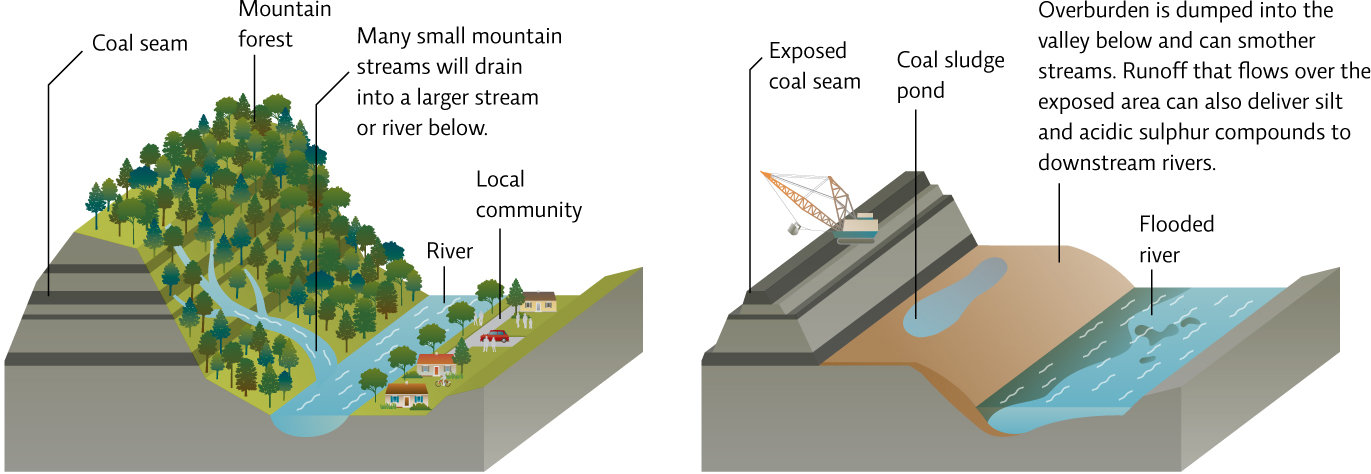

Hobet 21, which has claimed more than 4800 hectares of land, was once the site of several adjacent peaks. To get at the coal beneath those peaks, miners began by clear-cutting the forest above. Next, they drilled holes deep into the side of the mountain (some holes up to 120 metres deep), set dynamite in those holes, and blasted as much as 300 metres of mountain into a mass of rubble known as overburden. The miners repeated this process several times, until the layers of coal were exposed. Then, using buckets big enough to hold 20 midsized cars, they scooped that rubble into staircase-shaped mounds that filled in entire neighbouring valleys from the ground up—all told more than 70 million metric tons of overburden each year. The process obliterated the forest habitat, buried countless streams, and permanently reordered the land’s natural contours. [infographic 19.4]

340

This mountaintop removal mining is just one form of surface mining. The other type, known as strip mining, employs a similar process: workers use heavy equipment to remove and set aside overburden so that they can harvest the coal beneath. When they finish mining one strip of land, they return the overburden to the open pit and move on to a new strip. Strip mines are used in areas like Wyoming and Alberta, where the coal is close to the surface and the ground above is fairly level.

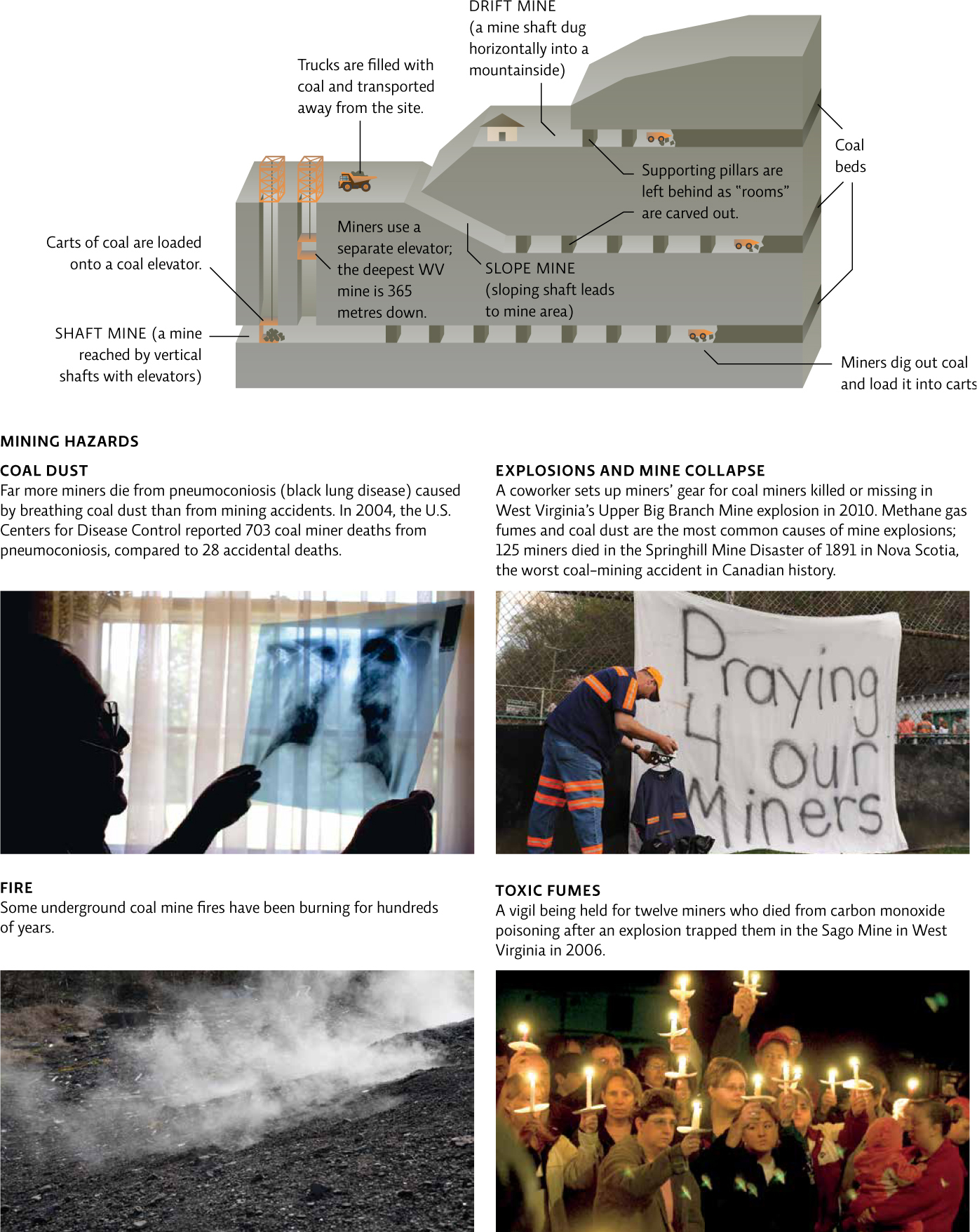

With their reliance on explosives and heavy equipment, surface mines are a far cry from the underground mines, also called subsurface mines, that sustained the Nelson family for so many generations. “When our daddies were mining, back in the ’40s and ’50s, the seams were as tall as full-grown men,” says Nelson, who since retiring has become a spokesperson for the anti-mining Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition. “So you could get at ’em the old-fashioned way, with pickaxes and sledgehammers.” Those days of plenty are gone, he says. Many of the coal seams that remain are too thin to be culled by human hands.

Subsurface mines come with their own challenges. They make up 60% of all coal mines worldwide (50% of those in the United States), but very few have operated in Canada since the Westray Mine disaster in Nova Scotia in 1992, in which an underground methane explosion killed 26 miners. Subsurface mines account for 10% of all methane release in the United States; methane is not only flammable, but is also a potent greenhouse gas [infographic 19.5].

Acid mine drainage is a problem in both surface and subsurface mines. Water leaches toxic substances such as sulphur from rock, creating acidic pools. This acid drainage contaminates soil and streams and is a major problem with both active and closed mines. Acidic water is directly toxic to many aquatic plants and animals, and alters nutrient cycles in ways that reverberate all the way up the food chain.

But subsurface mines also come with some advantages. Unlike surface mines, they don’t disrupt or permanently alter large surface areas. And because much of the work, however risky, is still done by workers rather than by machines, they employ more people. In Appalachia, 100 000 mining jobs were lost between 1980 and 1993 as underground mining gave way to mountaintop removal. The loss of traditional mining jobs has bred yet another controversy. Coal industry reps say that the riskier deep-mining jobs are being replaced with higher-paying, safer work—like demolition and heavy equipment operation. But that has not alleviated tension as more jobs are lost than replaced. “It’s a double insult,” says Tim Landry, a fourth-generation deep miner in West Virginia. “They’re not only destroying the land that we love, but they’re taking our jobs away, too.” In Canada, risky subsurface mining jobs pay around $30/hour, but many mining companies hire foreign workers who are willing to work for lower wages.

341

342

But job losses are not the only concern.