22.8 Confronting climate change is challenging.

Jack Rajala’s timber company owns over 14 000 hectares of commercial forest land in Itasca County, Minnesota. In recent years, he’s started doing things differently—namely, deliberately thinning out his paper birches in an effort to cultivate more oaks and white pines. That’s not to say that the paper birch isn’t valuable. But with massive die-offs underway throughout the region, Rajala needs to hedge his bets. “We think we can still facilitate birch,” he says. “But it may be an understory tree, not a canopy tree anymore.”

Rajala’s strategy is called resistance forestry; it includes a handful of techniques aimed at maintaining existing species in their current locations, even as the climate shifts. For example, prescribed burns that mimic historic fire patterns might bolster the ranks of fire-dependent species like paper birch, black spruce, and jack pine, allowing them to spread over a wider area and enhancing their genetic diversity. Planting seeds instead of saplings also helps species hold their ground; natural selection favours the hardiest field-grown seedlings, and so may yield a population better able to survive environmental stresses.

Scientists refer to such efforts, which are intended to minimize the extent or impact of climate change, as mitigation.

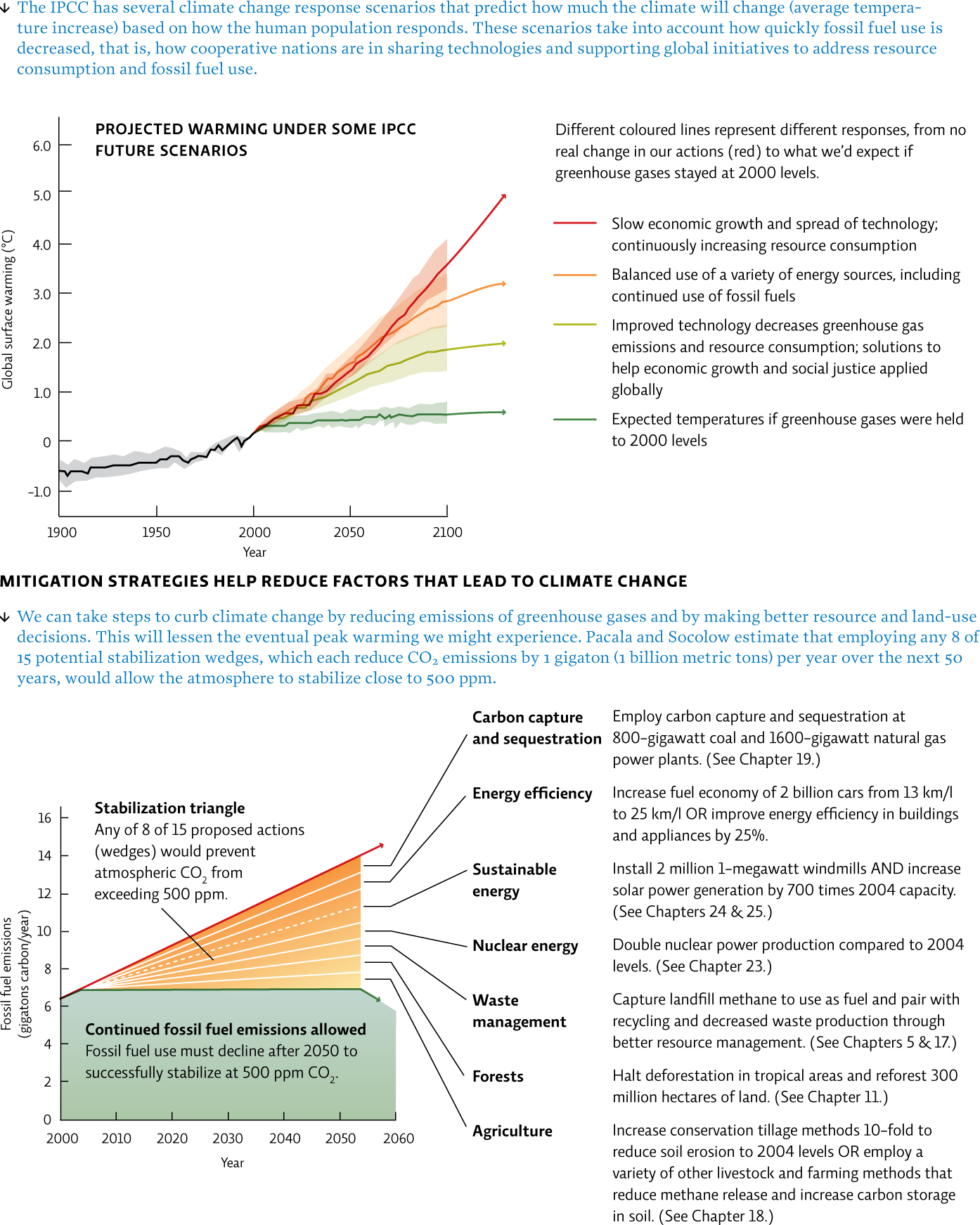

Mitigation includes any attempt to seriously curb the amount of CO2 we are releasing into the atmosphere—either by using carbon capture techniques to remove the greenhouse gas from our air and sequester it underground, or by consuming fewer fossil fuels to begin with. In 2004, Princeton University researchers Stephen Pacala and Robert Socolow proposed a “stabilization wedge” strategy—a step-by-step implementation of currently available technology; each step could prevent the release of 1 billion metric tons of carbon. Any 8 of the 15 steps, or “wedges,” would stabilize CO2 in the atmosphere at close to 525 ppm in the next 50 years. [infographic 22.10]

On a national or global scale, mitigation efforts can be facilitated in a variety of ways, such as command and control regulations that limit greenhouse gas release; tax breaks; green taxes (in this case, carbon taxes); and market-driven programs such as carbon cap-and-trade (see Chapter 21). Financial incentives that encourage the development and use of noncarbon fuels and more energy-efficient technology is critical (see Chapters 23 and 24).

No matter which strategies we employ, curbing greenhouse gas emissions will take a coordinated global effort, meaning that world superpowers like the European Union, the United States, and China will have to cooperate with the developing nations of the world. So far, efforts have been fraught with obstacles and lack of cooperation. In 1997, an international treaty called the Kyoto Protocol was ratified by every UN nation except the United States. The treaty set different but specific targets of CO2 release reduction for various nations; the United States objected because the protocol set much higher reduction requirements for developed countries than it did for developing nations. Notoriously, Canada withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in 2011; no other country has ever backed out of Kyoto. The federal environment minister justified the withdrawal by asserting that since neither China nor the United States, the two biggest emitters, were covered by the protocol, it would not work, and that since Canada had failed to meet its Kyoto CO2 emission targets thus far, it would have to back out to avoid paying the resulting fines.

Additional criticisms of Kyoto underscore the trouble with confronting such a global problem. Some of those who opposed Kyoto said that it went way too far in curbing greenhouse gas emission; they argued that placing any kind of limit on CO2 would hurt the economy because it would force industries to spend money updating their infrastructure, limit the amount of work they could do, and place them at a disadvantage compared with countries who had lower reduction targets under the treaty.

Other critics said that Kyoto did not go far enough; given the overwhelming evidence, these critics felt we needed to set much higher reduction targets to make any dent in the problem. They also felt that setting concrete, legally binding reduction targets in developed nations would actually stimulate the economy because it would force companies in those nations to develop new, cleaner, more efficient technologies that other countries would then buy.

The conflicting views on Kyoto illustrate why climate change is considered a wicked problem—one that is resistant to resolution because it is fraught with complexity, change, incomplete information, and lack of sociopolitical acceptance. Climate change is a classic example of this, and it challenges the bedrock of modern civilization: energy use. Some argue that applying the precautionary principle now could help avoid, or at least lessen, some of the most serious outcomes of a changing global climate.

409

410

At any rate, the Kyoto Protocol expired on December 31, 2012; so far, despite annual meetings, the international community has had no success in drafting a replacement treaty. The 2011 UN Climate Change Conference in Durban, South Africa, resulted in a legally binding agreement to adopt a future international climate treaty by 2015, but failed to produce any actual treaty. Some nations (including Germany and the United Kingdom) have made their own progress toward CO2 reductions, but other nations (including Canada, China, and the United States) have increased CO2 release since 1997.