26.3 Suburban sprawl consumes open space and wastes resources.

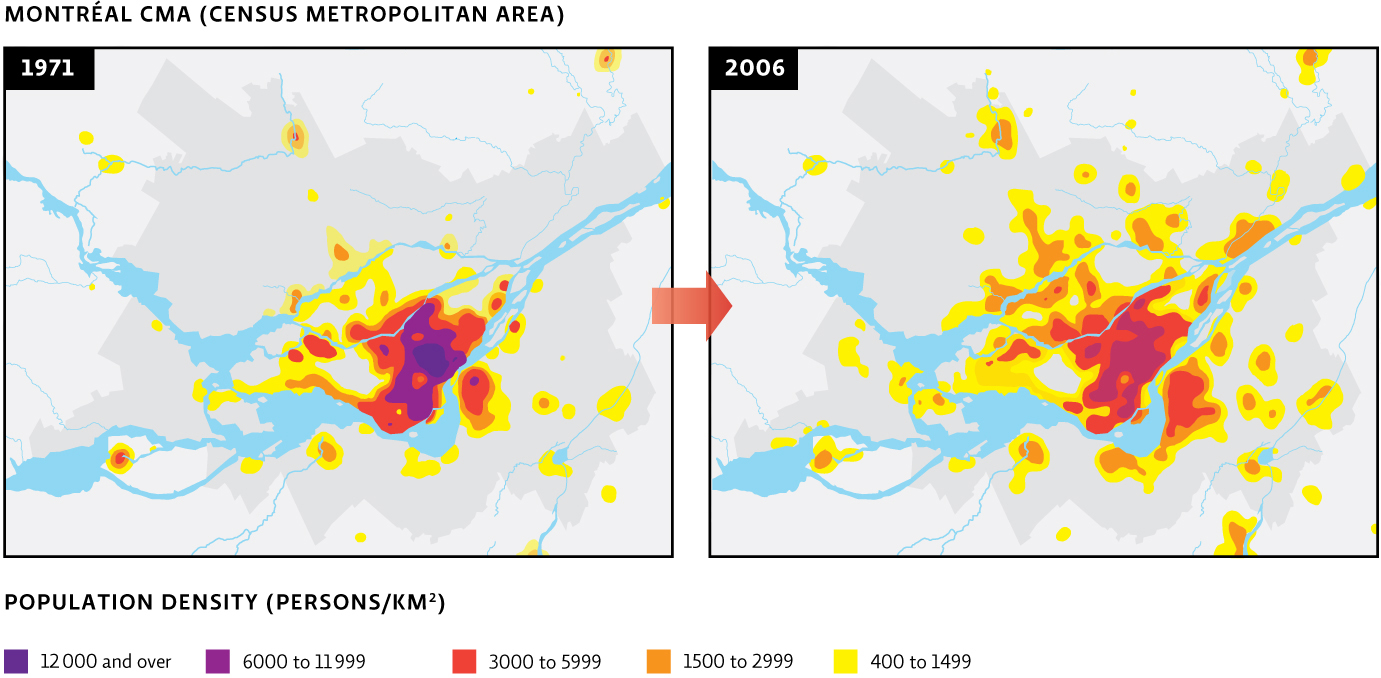

In the late 1940s when Carter’s father first bought the house Carter would grow up in, the South Bronx was a mostly European-descended white working class suburb of Manhattan. But, as more Hispanic and Black Americans moved to the area, seeking better opportunities, whites moved to nearby commuter towns. The process of people leaving a city centre for surrounding areas, originally made possible by the automobile and later by mass transit, is known as urban flight. While in many cities—especially those in developing nations—immigration exceeds emigration, urban flight today is triggered by a variety of forces, including overcrowding, noise and air pollution, the high cost of city living, and, in some cases, racial tensions. [infographic 26.4]

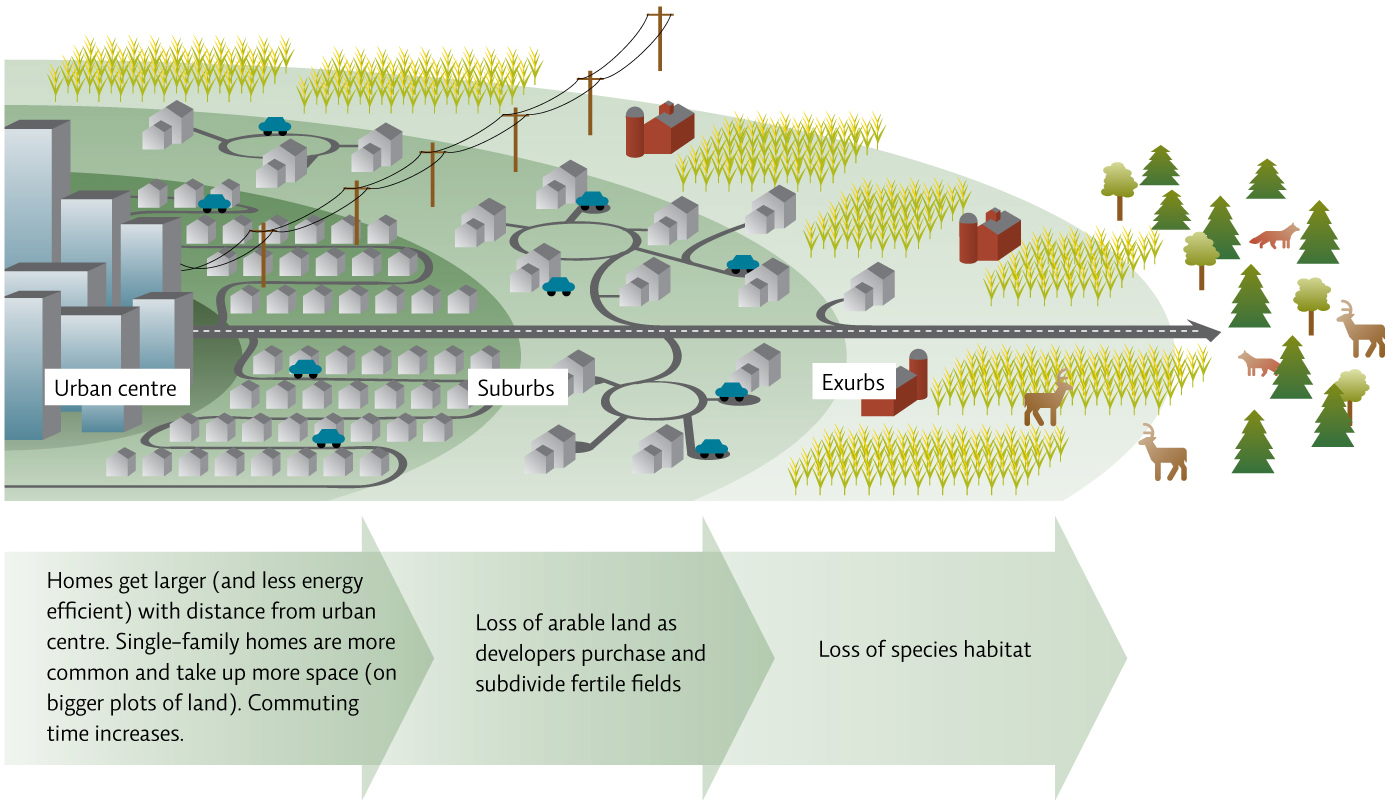

No matter what the cause, urban flight results in suburban sprawl—a slow conversion of rural areas into suburban and exurban ones. Exurbs are more sparsely populated towns beyond the immediate suburbs whose residents also commute into the city for work.

As its name suggests, suburban sprawl tends to spread out over long corridors in an unplanned and often inefficient manner. By covering ever-greater swaths of terrain with concrete and pavement, sprawl reduces the amount of land available for farming, wildlife, and ecosystem services. Because of the haphazard way in which they develop, the resulting communities are heavily dependent on driving. Unlike cities, which are densely populated and can accommodate mass transit systems, suburbs and exurbs force residents to drive almost everywhere they need to go. And because suburban homes are typically larger than urban ones (and exurban homes are often even larger than suburban ones), they tend to have a greater ecological footprint. [infographic 26.5]

481

Urban planners of today are well aware of these perils and often work to mitigate them. But in the 1960s, prolific U.S. urban planner Robert Moses was all too happy to accommodate urban flight and the sprawl that came with it. It was Moses who commissioned the Cross Bronx Expressway, a highway that enabled commuters from suburban Westchester County in the north to completely bypass the Bronx as they travelled in and out of Manhattan each day. But the expressway also displaced 600 000 Bronx residents and further segregated the ailing borough from the rest of New York City. “The South Bronx was utterly cut off,” says Marta Rodriguez, a lifelong Bronx resident and a colleague of Carter’s. “We didn’t stand a chance.”

To make matters worse, in the Bronx and elsewhere in the 1960s, urban flight in New York City led to redlining—the process whereby banks rule certain sections of a city off limits to any type of investment. Bronx landlords quickly discovered that if their neighbourhood was redlined, torching their buildings and collecting the insurance money would yield greater profits than renting or selling. By the 1970s, the burning of tenement houses had spiralled out of control, so much so that at one Yankees game, an addled sportscaster famously declared, “Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning.” And as the shopping centres and apartment buildings were shuttered or burned, other industries took their place—namely, the garbage disposal operations and auto parts manufacturers that had been shunned by wealthier enclaves. Before long, the South Bronx had been transformed into an industrial wasteland.

482

In most cities, including those in the United States and Canada, zoning laws—laws that restrict the type of development allowed in a given area—create a buffer between commercial and residential areas so that factories aren’t wedged between houses. But in the Bronx, such laws were routinely ignored. Without other options, area residents were forced to accept factories and warehouses built on the ashes of apartment complexes. And because these new industrial neighbours preferentially hired commuters from outside the Bronx, unemployment rates skyrocketed—along with crime, poverty, and asthma.

It turned out that the patch of waterfront Carter and Xena had stumbled upon was a relic of the Moses-era highway expansion, sitting as it did beneath the Sheridan Expressway, a stretch of highway originally meant to cut across the entire northeast Bronx. The Sheridan was abandoned when planners realized it would run through the Bronx Zoo, a popular tourist destination. But by then the damage was done. Hunts Point—Carter’s neighbourhood—had been isolated and the surrounding waterfront condemned to wasteland.

Carter knew that replacing the abandoned lot with a park would be a big first step toward righting some of the wrongs that her community had endured. The trees and plants would trap pollutants from the air, preventing them from infiltrating people’s lungs. The grass and soil would absorb rainwater so that it could no longer carry trash and detritus from the streets into the river. And claiming even a small patch of waterfront for themselves would give Carter and her neighbours a sense of ownership, not to mention a connection to nature and a place to stretch their legs.

Indeed, studies by urban planning expert Reid Ewing and others have shown that parks improve both the physical and psychological health of people who live near them. And cities themselves—cities that, like the Bronx, were once plagued by drug trafficking and rampant gun violence—have shown that more green space can also mean less crime. In Bogotá, Colombia, in the late 1990s, for example, a particularly environmentally conscious mayor noticed that while his city was designed to accommodate heavy automobile traffic, the vast majority of his electorate did not drive. So he narrowed municipal thorough-fares from five lanes to three, expanded bike lanes and pedestrian walkways, and established a string of parks and public plazas throughout the city. The result? People stopped littering. Crimes rates dropped. And slowly but surely, city residents reclaimed their streets.

483

Bogotá was not so different from the South Bronx, Carter thought. If that city could go green on a third-world budget, surely she and her colleagues could raise enough money to do the same. Starting with the $10,000 seed grant from the city parks department, they leveraged a small fortune in additional grants, donations, and private investment, until they had finalized plans to build a $3 million park, complete with gardens, grassy knolls, and East River kayaking. Hunts Point Riverside Park—the spot that Carter stumbled upon—would be the borough’s first waterfront park in more than 60 years. But that was just the beginning.

Carter knew that replacing the abandoned lot with a park would be a big first step toward righting some of the wrongs that her community had endured.