4.4 Factors that decrease the death rate can also decrease overall population growth rates.

When Qin Yijao’s mom was pregnant with him back in 1981, the one-child policy was being strictly enforced, and she already had a son. “People from the Communist Brigade said I couldn’t have a second baby,” she told National Public Radio (NPR) in a 2005 interview. “But I was determined. I needed a son to work our farm.” So taking care to evade the birth police, she snuck off and delivered her son in a cave. When she was found out, she was penalized. “I had to pay double the price for grain, and they confiscated our television and sewing machine.” In the end, she got to keep and raise her son. But at 30, he has never worked a single day on the farm. “I don’t even know where my mom’s farm plot is,” Qin also told NPR, adding that while he appreciates the risks his mother took, he and his wife have no desire for a second child themselves. The anecdote underscores a key point: Chinese culture has changed dramatically in the years since one-child was enacted, becoming much more urban and thus lessening the need for farmhand children. Many demographers say that such social changes may be more responsible for smaller families than the policy itself.

64

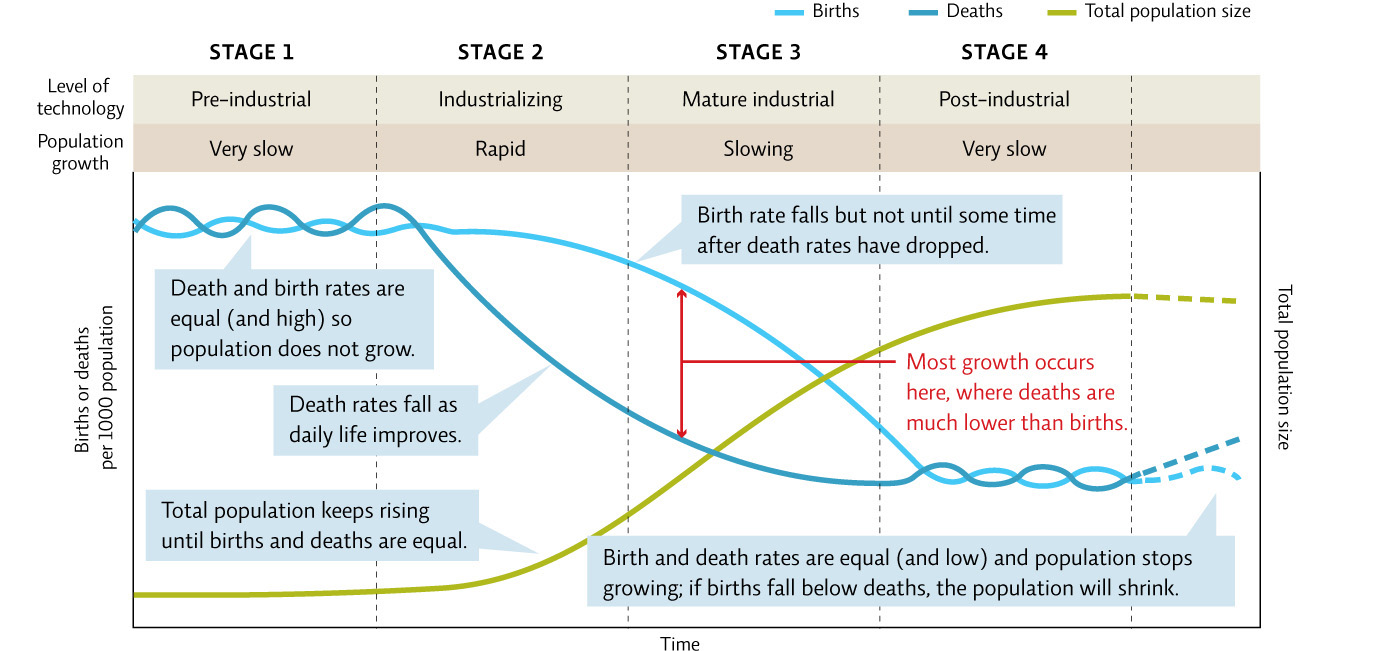

The demographic transition holds that as a country’s economy changes from pre-industrial to post-industrial, low birth and death rates replace high birth and death rates. The reasons are cultural as much as economic. As health care improves, infant mortality declines, and with it, the need for couples to have many children just to ensure that some make it to adulthood. And as cities grow and jobs materialize, the need for children to work the farm decreases. Meanwhile, as women find themselves with more opportunities, better health care, and greater access to education, they come to want fewer children. [infographic 4.4]

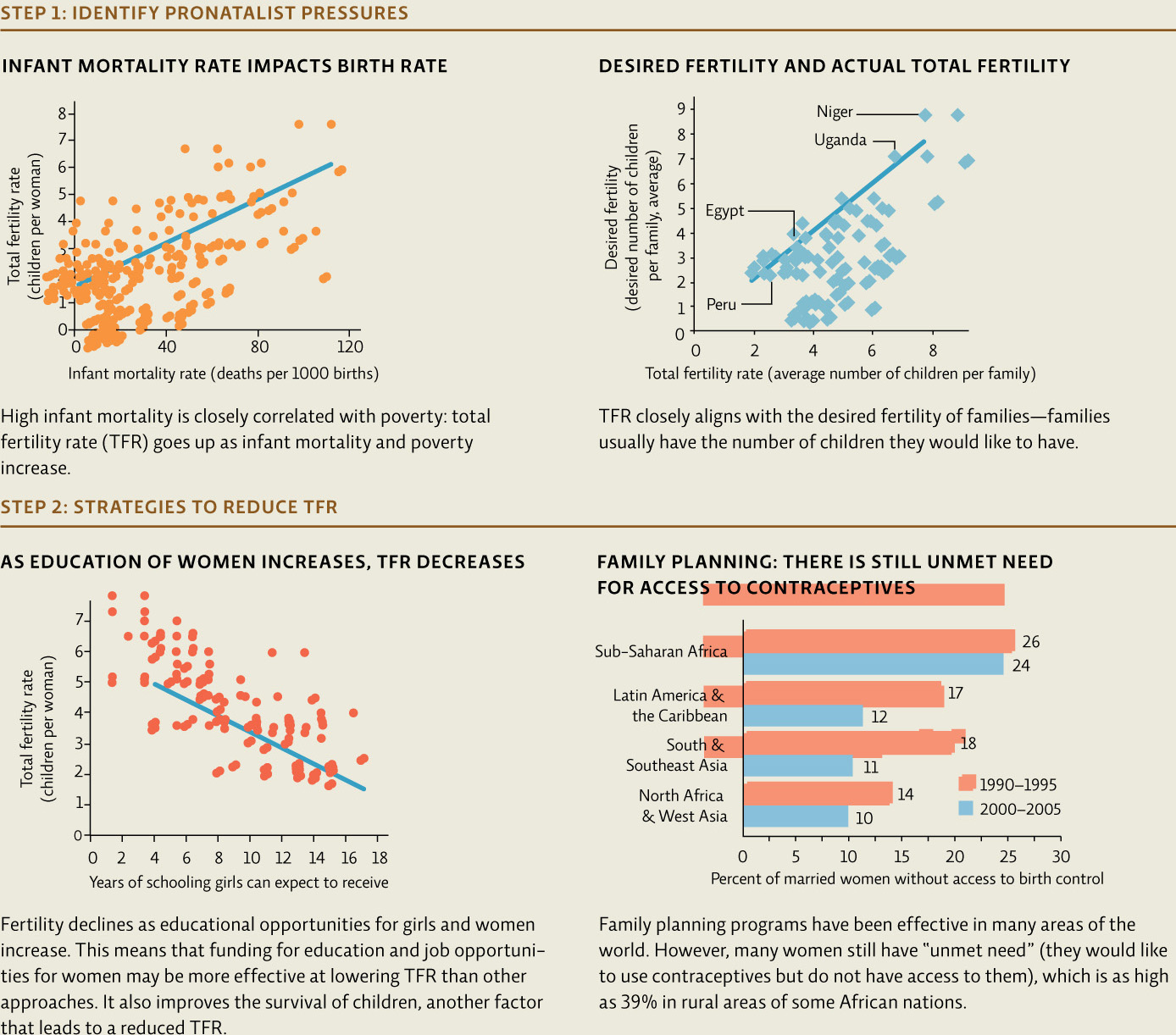

Developed countries, including Canada, the United States, and those of the European Union, have already undergone the demographic transition. Demographers are split over whether or not other countries are likely to do the same. But that uncertainty has not stopped world leaders from trying to cull lessons from the demographic transition model. Around the world, countries from Bangladesh to Brazil are working to reduce pronatalist pressures, increase gender equality, and combat poverty and infant mortality, all in an effort to improve standards of living, which in turn should lower fertility rates. The ultimate goal is to achieve zero population growth, when population size is stable, neither increasing nor decreasing. This occurs when the number of people born equals the number of people dying; in other words, replacement fertility rate is reached.

In most developed countries, the replacement rate is 2.1 (rather than the expected 2.0 to replace the parents), since a few children die before maturity and not every female has children. In countries with high infant mortality rates, the replacement rate is higher. Canada currently has a total fertility rate below replacement at 1.7. Without immigration, total population size would be shrinking.

There are at least a handful of clues suggesting that the demographic transition is as responsible for reductions in total fertility rates as the one-child policy is. Clue number one: the most significant fertility declines in the policy’s history coincided with the largest gains in the Chinese economy, not with periods of strict enforcement. Clue number two: many other countries have had substantial declines in fertility during the past 25 years without the use of strict population-control policies, including Japan, Singapore, and Thailand, whose fertility rates mirror those of China’s almost exactly—falling from 5 children per family in 1970 to 1.8 children per family in 2011.

65

“The parallels are hard to ignore,” says Therese Hesketh, a global health professor at University College London. “It suggests that China could have expected a continued reduction in its fertility rate just from continued economic development.” Feng, Director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy, puts it more bluntly. “The claim that ‘one-child’ prevented 400 million births is bogus for sure,” he says. “Many other countries experienced nearly identical fertility declines over the same time frame. So unless you say Chinese people are necessarily different from other populations, it’s very hard to argue the decline is due to government policy.”

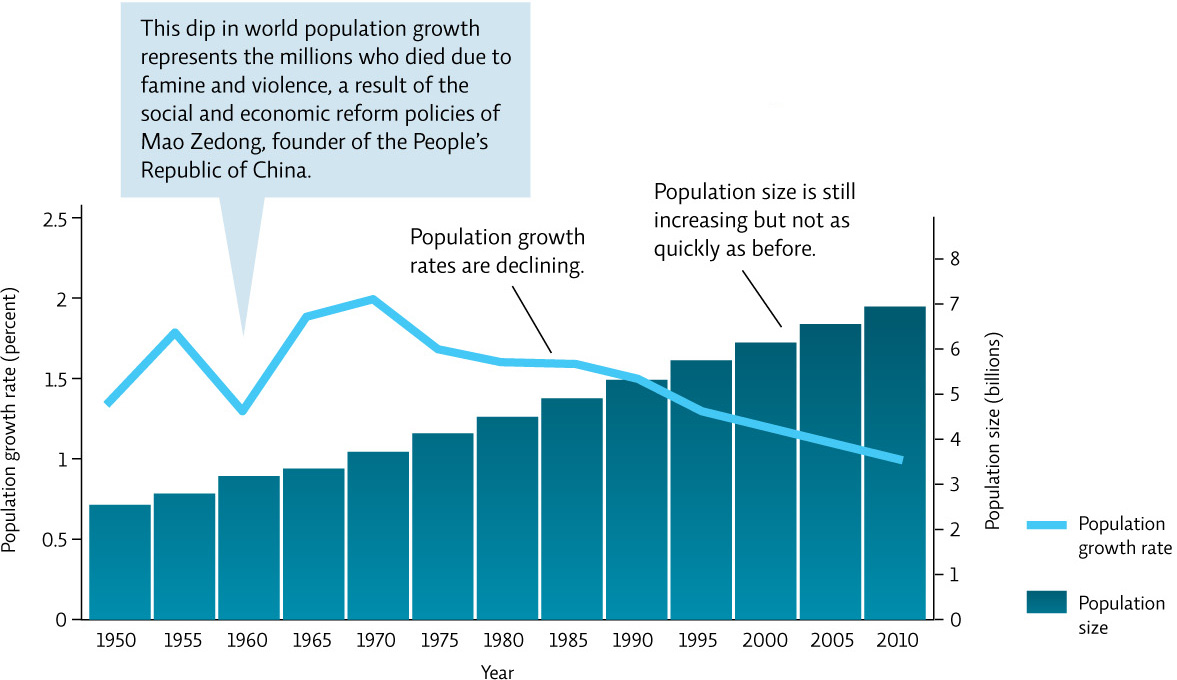

Worldwide, population growth rates are declining, but overall the number is still positive, so we are still increasing. [infographic 4.5] The United Nations estimates future population size leveling off somewhere between 6 and 16 billion people by 2100, depending on how quickly we reduce growth rates (see Infographic 4.1).

But if the predominant causes of declining fertility remain a source of debate, the consequences are becoming clearer and more stark by the day. Because the reasons for population growth are likely to be different in different regions, reaching zero population growth requires that the pronatalist pressures in each region be addressed. A variety of measures that don’t include government-restricted family size have proven successful.

Programs that address the needs of a given population and work within the cultural and religious traditions are likely to be most successful. Many demographers believe that addressing the social justice issues associated with overpopulation (poverty, high infant mortality, lack of education and opportunities for women) will prove the most instrumental in enabling countries with high TFRs to confront what lies ahead. [infographic 4.6]

66

DIFFERENT SOLUTIONS FOR DIFFERENT REGIONS

Thailand’s very successful family planning program started with better maternal and infant health care, family planning programs, and access to contraceptives, but also reflected the culture’s love of humour—from condom distribution at public gatherings to free vasectomies on the king’s birthday, to “ads” painted on the sides of water buffalo.

Kerala, India, a state in the world’s most populous country, adopted a population-control plan centred around the three “e’s”: education, employment, and equality. As a result, Kerala’s school system boasts more than a 90% literacy rate, which is almost identical between boys and girls. Educated women join the workforce before deciding to have children, and some 63% (compared to 48% in India as a whole) of women there use contraceptives. The state’s birth rate has stabilized at around 2.0.

In Brazil, the dropping birth rate over the past 40 years is attributed in part to pop culture. Families in popular TV shows are small—this coupled with rising opportunities for women and crowded living spaces in large cities, has produced a generation of young women whose desired family size is only one or two children.

67