4.6 Carrying capacity: is zero population growth enough?

The population size of a given area is not just determined by its birth and death rates but also by the migration of people in and out of its borders. Migration can be over large or small distances, across or within national boundaries, permanent or temporary (e.g., seasonal workers or refugees), and in large groups or small. Immigration refers to the movement of people into a given population; emigration refers to their movement out of a given population. Taken together, annual migration data and birth and death rates can tell us how quickly a population is changing in size. In China today, migration is mostly internal—from rural areas to urban ones, expanding those burgeoning populations and stressing the ability of the cities to meet the needs of the residents.

Every given environment has a carrying capacity—the maximum population size that the area can support. How large that population can be is determined by a range of forces, including the supply of nonrenewable resources, the rate of replenishment for renewable resources on which we depend, and the impact each individual person has on the environment (a degraded ecosystem can sustain far fewer people than a well-maintained, healthy one).

70

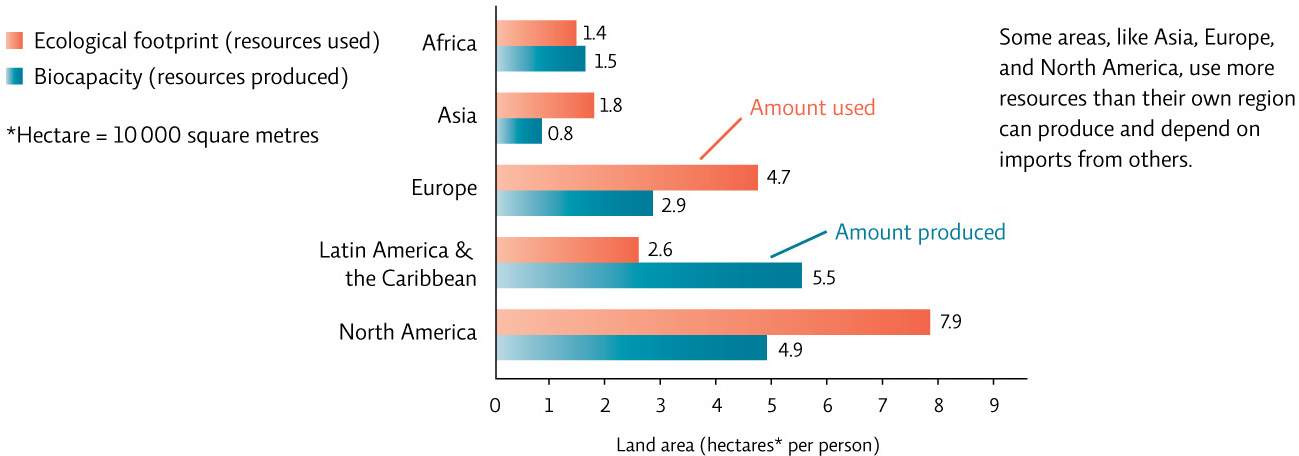

There are roughly 7 billion people on the planet today. Whether we stabilize at 9 or 10 billion or more depends on how quickly we lower TFR to achieve replacement fertility worldwide. Even at 7 billion people, we may have already exceeded the carrying capacity of Earth. One problem we face is our dependence on nonrenewable energy sources; they will not last indefinitely. But we are also overusing our biological resources. There are differences in how well different regions of the world live within the biocapacity (the ability of the ecosystem’s living components to produce and recycle resources, and assimilate wastes) of their own environments. North America in particular uses far more resources than its land area can provide, whereas Latin America and the Caribbean use less than half of the biocapacity of their region. This means nations like Canada and many others are importing resources from other regions.

The problem, then, is twofold: on the one hand, we are increasing, rapidly, in sheer numbers. On the other, we are consuming more resources per person than ever before. [infographic 4.8]

In general, population increase is a problem of the developing world—the highest fertility rates tend to be in the least developed countries, those that have yet to complete the demographic transition. Overconsumption, meanwhile, is a problem of more developed countries like Canada, where a single person might consume more food, fuel, and other resources (and thus place more strain on the environment) than a whole group of people in a less developed country like Sudan or Bangladesh. The impact humans have on Earth is thus due to a combination of factors—population size, affluence, and how we use resources, especially our use of technology, which tends to increase our overall use of resources. This is discussed more fully in Chapter 5.

In the years since the one-child policy was enacted, China has found itself careening from one end of this spectrum to the other. The problems that come with overpopulation—slums, epidemics, overwhelmed social services, and the production of high volumes of waste, for example—have been mitigated by a reduction in the fertility rate. But as fertility has declined, relative affluence has increased, and the Chinese are now straining the environment in a different way: by overconsuming.

It’s important to understand that overconsumption in one region or country can strain carrying capacity in other, disparate regions. In Bangladesh, for example, rising sea levels, spurred by global climate change, are pushing that nation’s carrying capacity to the brink. Most experts agree that a major driver of current climate change is rampant fossil fuel consumption, not by Bangladesh itself, but by developing nations, many of which are on the other side of the world. China now leads the way in the release of fossil fuel-based carbon emissions linked to climate change—because of its huge population and its growing affluence.

Ultimately, the question of how many people the planet can support may not be the right one. Trying to pinpoint whether Earth’s carrying capacity is 7 billion or 9 billion or even 16 billion is meaningless unless we identify what an acceptable quality of life is. And while overpopulation may be an issue with global significance and causes, it is one that ultimately plays out at the regional level: as land becomes degraded and water supplies depleted or polluted, people (and other organisms) live in an increasingly impoverished environment.

71