| CHAPTER 5 | ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS AND CONSUMPTION |

WALL TO WALL, CRADLE TO CRADLE

5.1 Successful businesses take a chance on going green

74

75

CORE MESSAGE

Human impact on Earth can be measured in terms of our ecological footprint, which is closely tied to the way we use resources. Our economic choices, both corporate and individual, tend to focus on short-term gain rather than long-term sustainability, but we can make better and more informed decisions by taking all the costs—economic, social, and environmental—of a given action into account. Using nature as a model can help us make more sustainable choices while still supporting a viable economy.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

What are ecosystem services? How can it be useful to place a monetary value on these services even if we know it will not be accurate?

What are ecosystem services? How can it be useful to place a monetary value on these services even if we know it will not be accurate? What is the concept of an ecological footprint, and how does it relate to our use of natural interest and natural capital?

What is the concept of an ecological footprint, and how does it relate to our use of natural interest and natural capital? What factors influence how much human actions impact the environment, and how can we reduce that impact?

What factors influence how much human actions impact the environment, and how can we reduce that impact? What are externalities and internalities in the business world and how do these concepts relate to the concept of true costs?

What are externalities and internalities in the business world and how do these concepts relate to the concept of true costs? How does ecologically based economics differ from mainstream economics, and how might ideas from ecological economics help industry and consumers make better choices?

How does ecologically based economics differ from mainstream economics, and how might ideas from ecological economics help industry and consumers make better choices?

76

It was the summer of 1994, and Ray Anderson was feeling pretty good. His Atlanta-based company, Interface Carpet, was the world’s leading seller of carpet tiles—small square pieces of carpet that are easier to install and replace than rolled carpet—and was raking in more than a billion dollars per year. One day, though, an associate from his research division approached him with a question. Some customers apparently wanted to know what Interface was doing for the environment. One had told Interface’s West Coast sales manager that, environmentally speaking, Interface “just didn’t get it.”

Anderson was dumbfounded. The carpet industry was not generally eco-conscious; after all, synthetic carpet is made from petroleum in a toxic process that releases significant amounts of air and water pollution, along with solid waste. Indeed, Interface used more than 450 000 metric tons of oil-derived raw materials each year, and its plant in LaGrange, Georgia, released more than 5 metric tons of carpet-trimming waste to landfills every day. “I could not think of what to say, other than ‘We obey the law, we comply,’” he recalls—in other words, his company did things by the book, in terms of the environment. Wasn’t that enough?

Desperate for inspiration, Anderson began leafing through The Ecology of Commerce, a book by environmental activist, entrepreneur, and writer Paul Hawken, which one of his sales managers had lent him. The book told the story of a small island in Alaska to which the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had introduced a population of reindeer during World War II. Although the reindeer thrived for a time on the available plants, eventually the population exploded beyond what the environment could support. They ultimately died out because, as Anderson explains, “you can’t go on consuming more than your environment is able to renew.” Yet that, he suddenly realized, was precisely what Interface was doing—using more resources than it could possibly renew. “As I read the book, it became clear that, God almighty, we’re on the wrong side of history, and we’ve got to do something.”

Anderson realized that he had to make changes to Interface—he needed to build it into a sustainable, environmentally sound business. “I didn’t know what it would cost, and I didn’t know what our customers would pay, so it was a leap of faith,” Anderson recalls.

The key, of course, was to invest in tools that reduced environmental impact without hurting the bottom line. A truly successful company is one that can reduce its environmental impact while making money, so it survives as a business and serves as a model of corporate responsibility and sustainability.

A few years ago, outdoor gear company Mountain Equipment Co-op (MEC), headquartered in Vancouver, was being honoured at the World Wilderness Congress for its decades of attention to the environmental impact of its products. On stage, CEO David Labistour was joined by representatives of two other businesses—a large cement company that has been protecting the Amazon rainforest, and Coca-Cola, which was being recognized for its work in replenishing aquifers in Mexico. After receiving his award, Labistour was accosted by an audience member who criticized him for standing with two large corporate entities. “You shouldn’t be up there with these huge businesses—it’s greed that destroys the environment,” he told Labistour. The CEO asked the man if he had a retirement account. Yes, came the answer. Did he expect it to grow over time? Yes, again. “Then you can’t fault companies for making money,” Labistour told the man.

77

But in the pursuit of profits, the choices businesses (and by extension, consumers) make have tremendous impacts on the environment. The amount and type of energy and water they use, the way they handle the waste they produce, the raw materials they use—these decisions affect not only business operations themselves, but also Earth as a whole, especially considering the magnitude of the resources and waste that some large businesses use and produce.

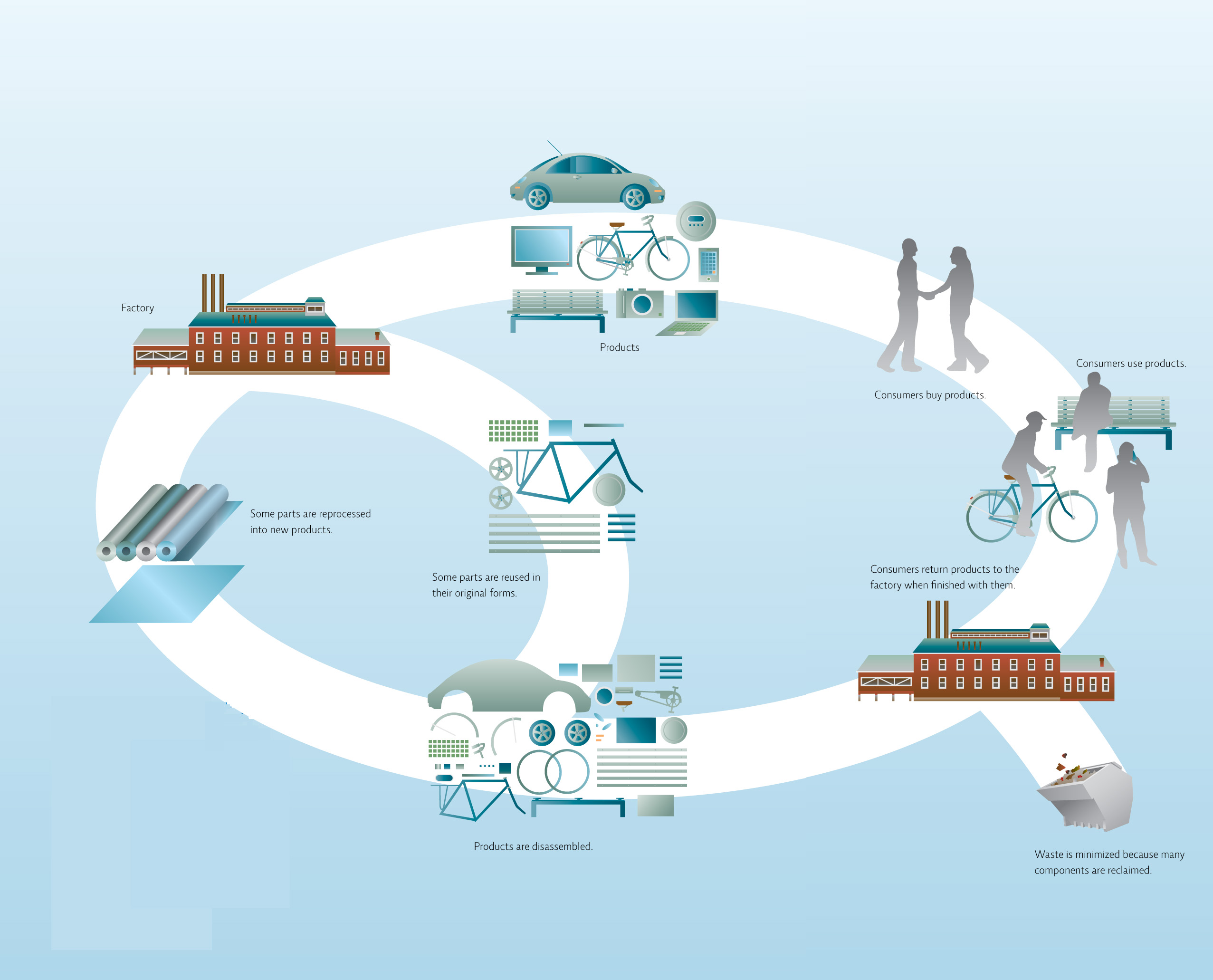

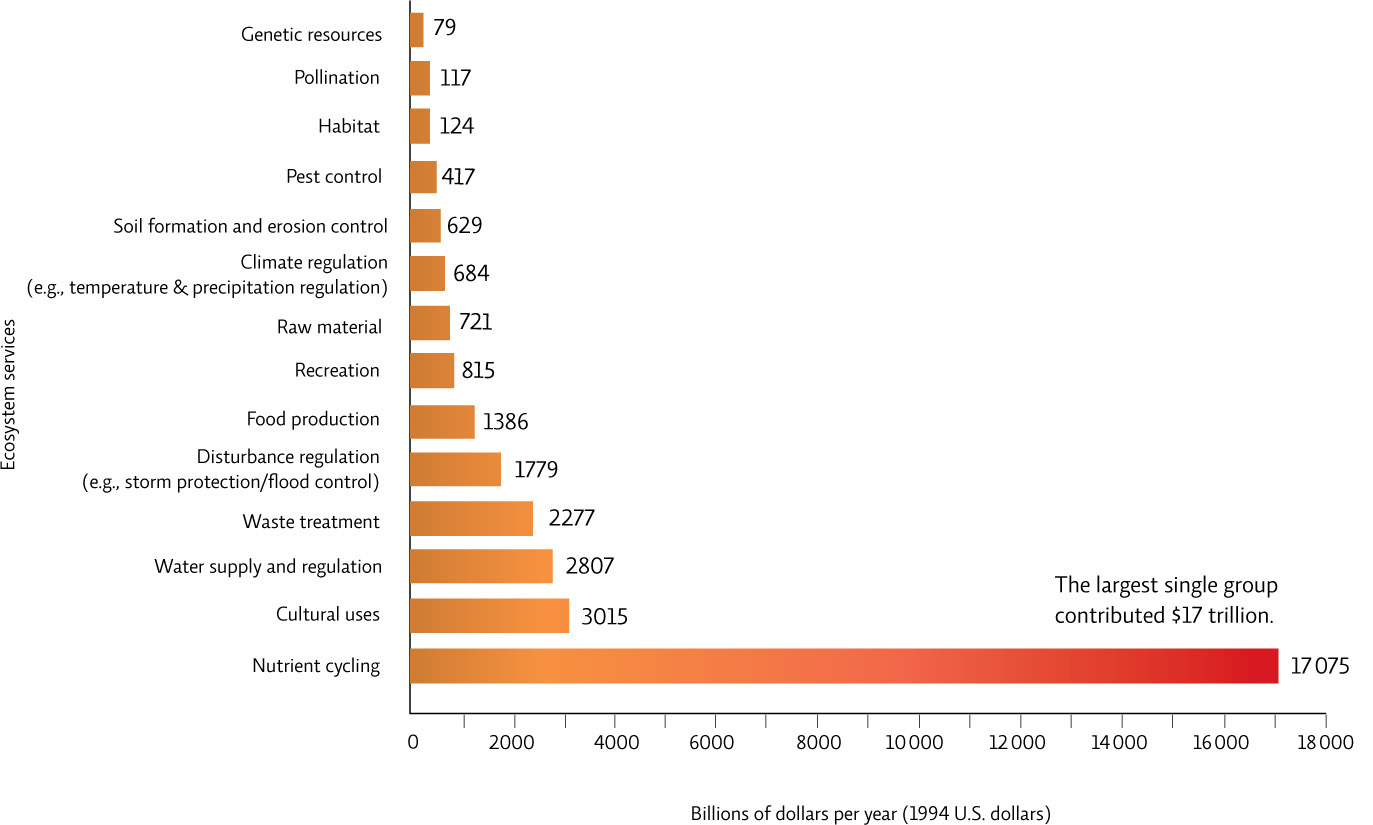

Environmentally mindful businesses like MEC and Interface, whether consciously or not, are applying principles that have always been at work in nature: since resources are finite, it’s important to recycle and to maximize energy efficiency. In this way, nature is an ecological model that can inspire economic models that enhance sustainability. After all, economics—the social science that analyzes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services—is not just about money. All of the resources on which we depend come from the environment. Environmental resources like timber and water can be considered ecosystem goods. Ecological processes like water purification, pollination, climate regulation, and nutrient cycling are essential ecosystem services. Some of these resources are invaluable because there are no substitutes—consider the oxygen produced by green plants, which we need in order to survive. [infographic 5.1]

78

79

When ecosystems are intact, they are naturally sustainable: they rely on renewable resources and also provide services that help to renew and recycle these resources. But ecosystems will only be able to provide us with their valuable goods and services as long as we let them. As Interface and MEC have realized, when we degrade ecosystems by using more from them than can be replenished, we threaten our planet’s ability to provide the services we need, which ultimately threatens our own future.