The place of government statistics

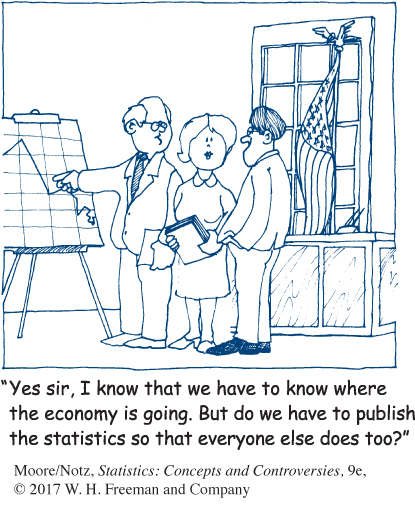

Modern nations run on statistics. Economic data, in particular, guide government policy and inform the decisions of private business and individuals. Price indexes and unemployment rates, along with many other, less publicized series of data, are produced by government statistical offices.

Some countries have a single statistical office, such as Statistics Canada (www.statcan.gc.ca). Others attach smaller offices to various branches of government. The United States is an extreme case: there are 72 federal statistical offices, with relatively weak coordination among them. The Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics are the largest, but you may at times use the products of the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the National Center for Health Statistics, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, or others in the federal government’s collection of statistical agencies.

A 1993 ranking of government statistical agencies by the heads of these agencies in several nations put Canada at the top, with the United States tied with Britain and Germany for sixth place. The top spots generally went to countries with a single, independent statistical office. In 1996, Britain combined its main statistical agencies to form a new Office for National Statistics (www.gov.uk/government/statistics). U.S. government statistical agencies remain fragmented.

What do citizens need from their government statistical agencies? First of all, they need data that are accurate and timely and that keep up with changes in society and the economy. Producing accurate data quickly demands considerable resources. Think of the large-scale sample surveys that produce the unemployment rate and the CPI. The major U.S. statistical offices have a good reputation for accuracy and lead the world in getting data to the public quickly. Their record for keeping up with changes is less impressive. The struggle to adjust the CPI for changing buying habits and changing quality is one issue. Another is the failure of U.S. economic statistics to keep up with trends such as the shift from manufacturing to services as the major type of economic activity. Business organizations have expressed strong dissatisfaction with the overall state of our economic data.

Much of the difficulty stems from lack of money. In the years after 1980, reducing federal spending was a political priority. Government statistical agencies lost staff and cut programs. Lower salaries made it hard to attract the best economists and statisticians to government. The level of government spending on data also depends on our view of what data the government should produce. In particular, should the government produce data that are used mainly by private business rather than by the government’s own policymakers? Perhaps such data should be either compiled by private concerns or produced only for those who are willing to pay. This is a question of political philosophy rather than statistics, but it helps determine what level of government statistics we want to pay for.

Freedom from political influence is as important to government statistics as accuracy and timeliness. When a statistical office is part of a government ministry, it can be influenced by the needs and desires of that ministry. The Census Bureau is in the Department of Commerce, which serves business interests. The BLS is in the Department of Labor. Thus, business and labor each has “its own” statistical office. The professionals in the statistical offices successfully resist direct political interference—a poor unemployment report is never delayed until after an election, for example. But indirect influence is clearly present. The BLS must compete with other Department of Labor activities for its budget, for example. Political interference with statistical work seems to be increasing, as when Congress refused to allow the Census Bureau to use sample surveys to correct for undercounting in the 2000 census. Such corrections are convincing to statisticians, but not necessarily to the general public. Congress, not without justification, considers the public legitimacy of the census to be as important as its technical perfection. Thus, from Congress’s point of view, political interference was justified even though the decision was disappointing to statisticians.

The 1996 reorganization of Britain’s statistical offices was prompted in part by a widespread feeling that political influence was too strong. The details of how unemployment is measured in Britain were changed many times in the 1980s, for example, and almost all the changes had the effect of reducing the reported unemployment rate—just what the government wanted to see.

We favor a single “Statistics USA” office not attached to any other government ministry, as in Canada. Such unification might also help the money problem by eliminating duplication. It would at least allow a central decision about which programs deserve a larger share of limited resources. Unification is unlikely, but stronger coordination of the many federal statistical offices could achieve many of the same ends.