Talking about data: Individuals and variables

Statistics is the science of data. We could almost say “the art of data” because good judgment and even good taste, along with good math, make good statistics. A big part of good judgment lies in deciding what you must measure in order to produce data that will shed light on your concerns. We begin with some vocabulary to describe the raw materials that go into data.

Individuals and variables

Individuals are the objects described by a set of data. Individuals may be people, but they may also be animals or things.

A variable is any characteristic of an individual. A variable can take different values for different individuals.

For example, here are the first lines of a professor’s data set at the end of a statistics course:

| NAME | MAJOR | POINTS | GRADE |

| ADVANI, SURA | COMM | 397 | B |

| BARTON, DAVID | HIST | 323 | C |

| BROWN, ANNETTE | LIT | 446 | A |

| CHIU, SUN | PSYC | 405 | B |

| CORTEZ, MARIA | PSYC | 461 | A |

The individuals are students enrolled in the course. In addition to each student’s name, there are three variables. The first says what major a student has chosen. The second variable gives the student’s total points out of 500 for the course, and the third records the grade received.

Statistics deals with numbers, but not all variables are numerical. Some are “categorical” and simply place an individual into one of several groups or categories. Of the three variables in the professor’s data set, only total points has numbers as its values. Major and grade are categorical, and to do statistics with these variables, we use counts or percentages. We might give the percentage of students who got an A, for example, or the percentage who are psychology majors.

Categorical and numerical variables

A categorical variable simply places an individual into one of several groups or categories.

A numerical variable takes numerical values for which arithmetic operations such as adding and averaging make sense. A numerical variable is sometimes referred to as a quantitative variable.

Bad judgment in choosing variables can lead to data that cost lots of time and money but don’t shed light on the world. What constitutes good judgment can be controversial. Here are examples of the challenges in deciding what data to collect.

EXAMPLE 1 Who recycles?

Who takes the trouble to recycle? Researchers spent lots of time and money weighing the stuff put out for recycling in two neighborhoods in a California city; call them Upper Crust and Lower Mid. The individuals here are households because trash and recycling pickup are done for residences, not for people one at a time. The variable measured was the weight in pounds of the curbside recycling basket each week.

The Upper Crust households contributed more pounds per week on the average than did the folk in Lower Mid. Can we say that the rich are more serious about recycling? No. Someone noticed that Upper Crust recycling baskets contained lots of heavy glass wine bottles. In Lower Mid, they put out lots of light plastic soda bottles and light metal beer and soda cans. The conclusion: weight tells us little about commitment to recycling.

EXAMPLE 2 What’s your race?

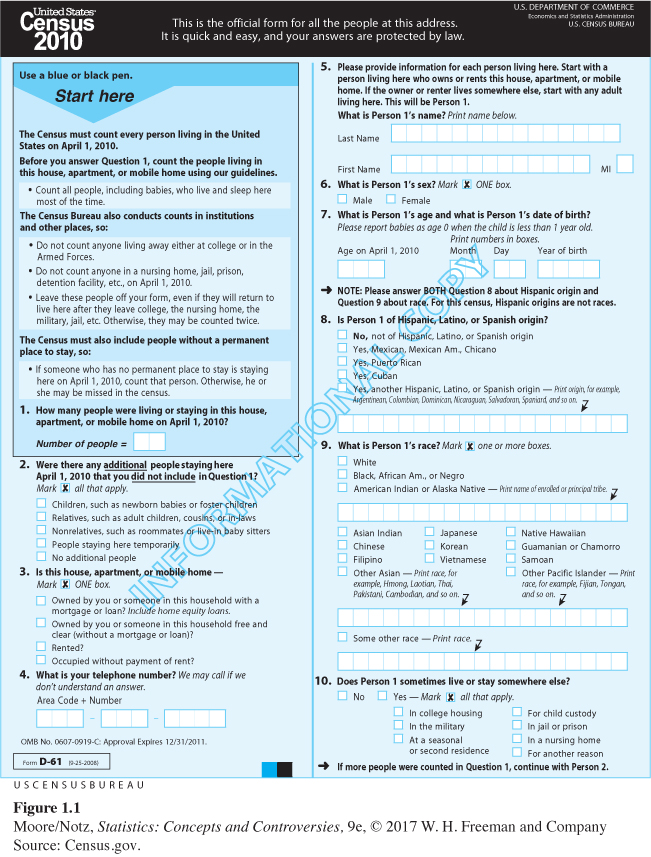

The U.S. census asks, “What is this person’s race?” for every person in every household. “Race” is a variable, and the Census Bureau must say exactly how to measure it. The census form does this by giving a list of races. Years of political squabbling lie behind this list.

How many races shall we list, and what names shall we use for them? Shall we have a category for people of mixed race? Asians wanted more national categories, such as Filipino and Vietnamese, for the growing Asian population. Pacific Islanders wanted to be separated from the larger Asian group. Black leaders did not want a mixed-race category, fearing that many blacks would choose it and so reduce the official count of the black population.

The 2010 census form (see Figure 1.1) ended up with six Asian groups (plus “Other Asian”) and three Pacific Island groups (plus “Other Pacific Islander”). There is no “mixed-race” group, but you can mark more than one race. That is, people claiming mixed race can count as both so that the total of the racial group counts in 2010 is larger than the population count. Unable to decide what the proper term for blacks should be, the Census Bureau settled on “Black, African American, or Negro.” What about Hispanics? That’s a separate question because Hispanics can be of any race. Again unable to choose a short name that would satisfy everyone, the Census Bureau decided to ask if you are of “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.”

The fight over “race” reminds us that data reflect society. Race is a social idea, not a biological fact. In the census, you say what race you consider yourself to be. Race is a sensitive issue in the United States, so the fight is no surprise, and the Census Bureau’s diplomacy seems a good compromise.