Hypotheses and P-values

Tests of significance refine (and perhaps hide) this basic reasoning. In most studies, we hope to show that some definite effect is present in the population. In Example 1, we suspect that a majority of coffee drinkers prefer fresh-

Null hypothesis H0

The claim being tested in a statistical test is called the null hypothesis. The test is designed to assess the strength of the evidence against the null hypothesis. Usually, the null hypothesis is a statement of “no effect’’ or “no difference.’’

The term “null hypothesis’’ is abbreviated H0 and is read as “H-

H0: p = 0.5

![]() Gotcha! A tax examiner suspects that Ripoffs, Inc., is issuing phony checks to inflate its expenses and reduce the tax it owes. To learn the truth without examining every check, she boots up her computer. The first digits of real data follow well-

Gotcha! A tax examiner suspects that Ripoffs, Inc., is issuing phony checks to inflate its expenses and reduce the tax it owes. To learn the truth without examining every check, she boots up her computer. The first digits of real data follow well-

The statement we hope or suspect is true instead of H0 is called the alternative hypothesis and is abbreviated Ha. In Example 1, the alternative hypothesis is that a majority of the population favor fresh coffee. In terms of the population parameter, this is

Ha: p > 0.5

A significance test looks for evidence against the null hypothesis and in favor of the alternative hypothesis. The evidence is strong if the outcome we observe would rarely occur if the null hypothesis is true but is more probable if the alternative hypothesis is true. For example, it would be surprising to find 36 of 50 subjects favoring fresh coffee if, in fact, only half of the population feel this way. How surprising? A significance test answers this question by giving a probability: the probability of getting an outcome at least as far as the actually observed outcome from what we would expect when H0 is true. What counts as “far from what we would expect’’ depends on Ha as well as H0. In the taste test, the probability we want is the probability that 36 or more of 50 subjects favor fresh coffee. If the null hypothesis p = 0.5 is true, this probability is very small (0.001). That’s good evidence that the null hypothesis is not true.

P-value

The probability, computed assuming that H0 is true, that the sample outcome would be as extreme or more extreme than the actually observed outcome is called the P-value of the test. The smaller the P-value is, the stronger is the evidence against H0 provided by the data.

In practice, most statistical tests are carried out by computer software that calculates the P-value for us. It is usual to report the P-value in describing the results of studies in many fields. You should, therefore, understand what P-values say even if you don’t do statistical tests yourself, just as you should understand what “95% confidence’’ means even if you don’t calculate your own confidence intervals.

EXAMPLE 2 Count Buffon’s coin

The French naturalist Count Buffon (1707–

ˆp=20484040=0.507

That’s a bit more than one-

The hypotheses. The null hypothesis says that the coin is balanced (p = 0.5). We did not suspect a bias in a specific direction before we saw the data, so the alternative hypothesis is just “the coin is not balanced.’’ The two hypotheses are

H0: p = 0.5

Ha: p ≠ 0.5

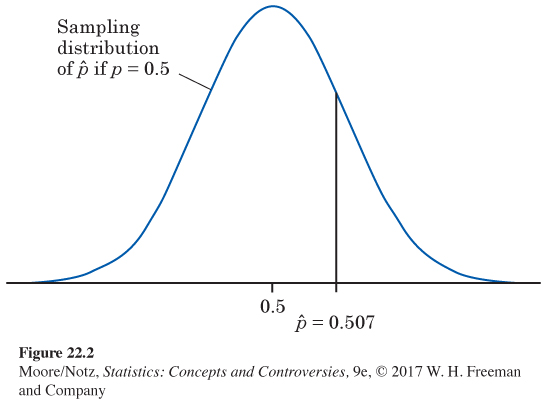

The sampling distribution. If the null hypothesis is true, the sample proportion of heads has approximately the Normal distribution with

mean = p = 0.5

standard deviation=p(1–

= 0.00786

The data. Figure 22.2 shows this sampling distribution with Buffon’s sample outcome marked. The picture already suggests that this is not an unlikely outcome that would give strong evidence against the claim that p = 0.5.

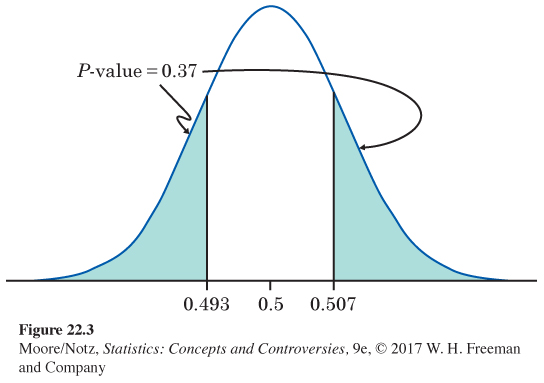

The P-value. How unlikely is an outcome as far from 0.5 as Buffon’s ? Because the alternative hypothesis allows p to lie on either side of 0.5, values of far from 0.5 in either direction provide evidence against H0 and in favor of Ha. The P-value is, therefore, the probability that the observed lies as far from 0.5 in either direction as the observed . Figure 22.3 shows this probability as area under the Normal curve. It is P = 0.37.

The conclusion. A truly balanced coin would give a result this far or farther from 0.5 in 37% of all repetitions of Buffon’s trial. His result gives no reason to think that his coin was not balanced.

The alternative Ha: p > 0.5 in Example 1 is a one-

NOW IT’S YOUR TURN

Question 22.1

22.1 Coin tossing. We do not have the patience of Count Buffon, so we tossed a coin only 50 times. We got 21 heads. The proportion of heads is

This is less than one-

22.1 The hypotheses. The null hypothesis says that the coin is balanced (p = 0.5). We do not suspect a bias in a specific direction before we see the data, so the alternative hypothesis is just “the coin is not balanced.” The two hypotheses are

H0 : p = 0.5

Ha : p ≠ 0.5

The sampling distribution. If the null hypothesis is true, the sample proportion of heads has approximately the Normal distribution with

mean = p = 0.5

= 0.0707