How to experiment badly

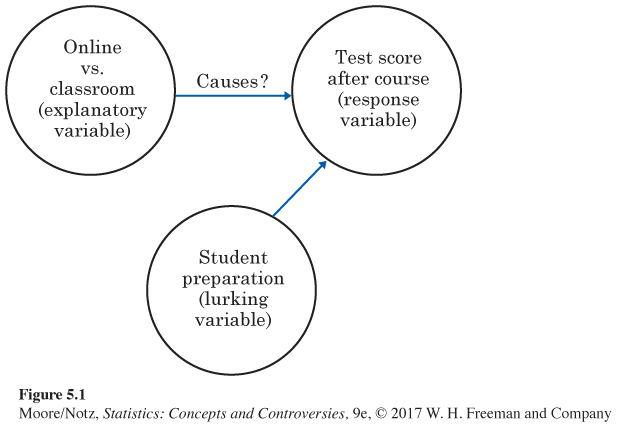

Do students who take a course via the Web learn as well as those who take the same course in a traditional classroom? The best way to find out is to assign some students to the classroom and others to the Web. That’s an experiment. The Nova Southeastern University study was not an experiment because it imposed no treatment on the student subjects. Students chose for themselves whether to enroll in a classroom or an online version of a course. The study simply measured their learning. It turns out that the students who chose the online course were very different from the classroom students. For example, their average score on a test on the course material given before the courses started was 40.70, against only 27.64 for the classroom students. It’s hard to compare in-class versus online learning when the online students have a big head start. The effect of online versus in-class instruction is hopelessly mixed up with influences lurking in the background. Figure 5.1 shows the mixed-up influences in picture form.

Lurking variables

A lurking variable is a variable that has an important effect on the relationship among the variables in a study but is not one of the explanatory variables studied.

Two variables are confounded when their effects on a response variable cannot be distinguished from each other. The confounded variables may be either explanatory variables or lurking variables.

In the Nova Southeastern University study, student preparation (a lurking variable) is confounded with the explanatory variable. The study report claims that the two groups did equally well on the final test. We can’t say how much of the online group’s performance is due to their head start. That a group that started with a big advantage did no better than the more poorly prepared classroom students is not very impressive evidence of the wonders of Web-based instruction. Here is another example, one in which a second experiment was proposed to untangle the confounding.

EXAMPLE 3 Pig whipworms and the need for further study

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease. An experiment reported in Gut, a British medical journal, claimed that a drink containing thousands of pig whipworm eggs was effective in reducing abdominal pain, bleeding, and diarrhea associated with the disease.

Experiments that study the effectiveness of medical treatments on actual patients are called clinical trials. The clinical trial that suggested that a drink made from pig whipworm eggs might be effective in relieving the symptoms of Crohn’s disease had a “one-track” design—that is, only a single treatment was applied:

Impose treatment → Measure response

Pig whipworms → Reduced symptoms?

The patients did report reduced symptoms, but we can’t say that the pig whipworm treatment caused the reduced symptoms. It might be just the placebo effect. A placebo is a dummy treatment with no active ingredients. Many patients respond favorably to any treatment, even a placebo. This response to a dummy treatment is the placebo effect. Perhaps the placebo effect is in our minds, based on trust in the doctor and expectations of a cure. Perhaps it is just a name for the fact that many patients improve for no visible reason. The one-track design of the experiment meant that the placebo effect was confounded with any effect the pig whipworm drink might have.

The researchers recognized this and urged further study with a better-designed experiment. Such an experiment might involve dividing subjects with Crohn’s disease into two groups. One group would be treated with the pig whipworm drink as before. The other would receive a placebo. Subjects in both groups would not know which treatment they were receiving. Nor would the physicians recording the symptoms of the subjects know which treatment a subject received so that their diagnosis would not be influenced by such knowledge. An experiment in which neither subjects nor physicians recording the symptons know which treatment was received is called double-blind.

Both observational studies and one-track experiments often yield useless data because of confounding with lurking variables. It is hard to avoid confounding when only observation is possible. Experiments offer better possibilities, as the pig whipworm experiment shows. This experiment could be designed to include a group of subjects who receive only a placebo. This would allow us to see whether the treatment being tested does better than a placebo and so has more than the placebo effect going for it. Effective medical treatments pass the “placebo test” by outperforming a placebo.