Randomized comparative experiments

The first goal in designing an experiment is to ensure that it will show us the effect of the explanatory variables on the response variables. Confounding often prevents one-track experiments from doing this. The remedy is to compare two or more treatments. When confounding variables affect all subjects equally, any systematic differences in the responses of subjects receiving different treatments can be attributed to the treatments rather than to the confounding variables. This is the idea behind the use of a placebo. All subjects are exposed to the placebo effect because all receive some treatment. Here is an example of a new medical treatment that passes the placebo test in a direct comparison.

EXAMPLE 4 Sickle-cell anemia

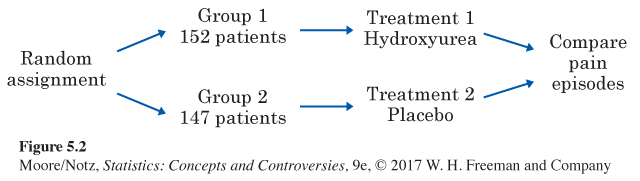

Sickle-cell anemia is an inherited disorder of the red blood cells that in the United States affects mostly blacks. It can cause severe pain and many complications. The National Institutes of Health carried out a clinical trial of the drug hydroxyurea for treatment of sickle-cell anemia. The subjects were 299 adult patients who had had at least three episodes of pain from sickle-cell anemia in the previous year. An episode of pain was defined to be a visit to a medical facility that lasted more than four hours for acute sickling-related pain. The measurement of the length of the visit included all time spent after registration at the medical facility, including the time spent waiting to see a physician.

Simply giving hydroxyurea to all 299 subjects would confound the effect of the medication with the placebo effect and other lurking variables such as the effect of knowing that you are a subject in an experiment. Instead, approximately half of the subjects received hydroxyurea, and the other half received a placebo that looked and tasted the same. All subjects were treated exactly the same (same schedule of medical checkups, for example) except for the content of the medicine they took. Lurking variables, therefore, affected both groups equally and should not have caused any differences between their average responses.

The two groups of subjects must be similar in all respects before they start taking the medication. Just as in sampling, the best way to avoid bias in choosing which subjects get hydroxyurea is to allow impersonal chance to make the choice. A simple random sample of 152 of the subjects formed the hydroxyurea group; the remaining 147 subjects made up the placebo group. Figure 5.2 outlines the experimental design.

The experiment was stopped ahead of schedule because the hydroxyurea group had many fewer pain episodes than the placebo group. This was compelling evidence that hydroxyurea is an effective treatment for sickle-cell anemia, good news for those who suffer from this serious illness.

Figure 5.2 illustrates the simplest randomized comparative experiment, one that compares just two treatments. The diagram outlines the essential information about the design: random assignment to groups, one group for each treatment, the number of subjects in each group (it is generally best to keep the groups similar in size), what treatment each group gets, and the response variable we compare. Random assignment of subjects to groups can use any of the techniques discussed in Chapter 2. For example, we could choose a simple random sample, labeling the 299 subjects 1 to 299, then using software to select the 152 subjects for Group 1. The remaining 147 subjects form Group 2. Lacking software, label the 299 subjects 001 to 299 and read three-digit groups from the table of random digits (Table A) until you have chosen the 152 subjects for Group 1. The remaining 147 subjects form Group 2.

The placebo group in Example 4 is called a control group because comparing the treatment and control groups allows us to control the effects of lurking variables. A control group need not receive a dummy treatment such as a placebo. In Example 2, the students who were randomly assigned to the session providing access to brochures on sexual assault (as was common university practice) were considered to be a control group. Clinical trials often compare a new treatment for a medical condition—not with a placebo, but with a treatment that is already on the market. Patients who are randomly assigned to the existing treatment form the control group. To compare more than two treatments, we can randomly assign the available experimental subjects to as many groups as there are treatments. Here is an example with three groups.

EXAMPLE 5 Conserving energy

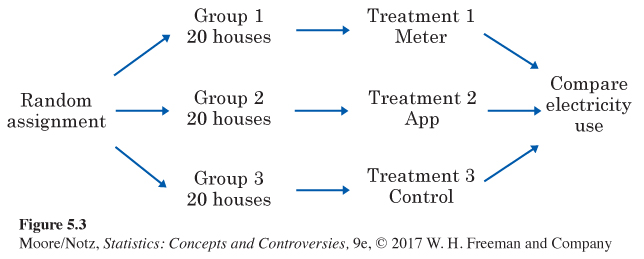

Many utility companies have introduced programs to encourage energy conservation among their customers. An electric company considers placing electronic meters in households to show what the cost would be if the electricity use at that moment continued for a month. Will meters reduce electricity use? Would cheaper methods work almost as well? The company decides to design an experiment.

One cheaper approach is to give customers an app and information about using the app to monitor their electricity use. The experiment compares these two approaches (meter, app) and also a control. The control group of customers receives information about energy conservation but no help in monitoring electricity use. The response variable is total electricity used in a year. The company finds 60 single-family residences in the same city willing to participate, so it assigns 20 residences at random to each of the three treatments. Figure 5.3 outlines the design.

To carry out the random assignment, label the 60 households 1 to 60; then use software to select an SRS of 20 to receive the meters. From those not selected, use software to select the 20 to receive the app. The remaining 20 form the control group. Lacking software, label the 60 households 01 to 60. Enter Table A to select an SRS of 20 to receive the meters. Continue in Table A, selecting 20 more to receive the app. The remaining 20 form the control group.

NOW IT’S YOUR TURN

Question 5.1

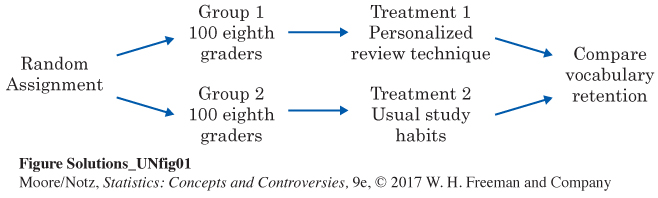

5.1 Improving students’ long-term knowledge retention. Can a technique known as personalized review improve students’ ability to remember material learned in a course? To answer this question, a researcher recruited 200 eighth-grade students who were taking introductory Spanish. She assigned 100 students to a class training students to use the personalized review technique as part of their study habits. The other 100 continued to use their usual study habits. The researcher examined both groups on Spanish vocabulary four weeks after the school year ended. Outline the design of this study using a diagram like Figures 5.2 and 5.3.