Double-blind experiments

Placebos “work.” That bare fact means that medical studies must take special care to show that a new treatment is not just a placebo. Part of equal treatment for all is to be sure that the placebo effect operates on all subjects.

EXAMPLE 2 The powerful placebo

Want to help balding men keep their hair? Give them a placebo—one study found that 42% of balding men maintained or increased the amount of hair on their heads when they took a placebo. Another study told 13 people who were very sensitive to poison ivy that the stuff being rubbed on one arm was poison ivy. It was a placebo, but all 13 broke out in a rash. The stuff rubbed on the other arm really was poison ivy, but the subjects were told it was harmless—and only 2 of the 13 developed a rash.

When the ailment is vague and psychological, like depression, some experts think that about three-quarters of the effect of the most widely used drugs is just the placebo effect. Others disagree (see Web Exercise 6.31). The strength of the placebo effect in medical treatments is hard to pin down because it depends on the exact environment. How enthusiastic the doctor is seems to matter a lot. But “placebos work” is a good place to start when you think about planning medical experiments.

The strength of the placebo effect is a strong argument for randomized comparative experiments. In the baldness study, 42% of the placebo group kept or increased their hair, but 86% of the men getting a new drug to fight baldness did so. The drug beats the placebo, so it has something besides the placebo effect going for it. Of course, the placebo effect is still part of the reason this and other treatments work.

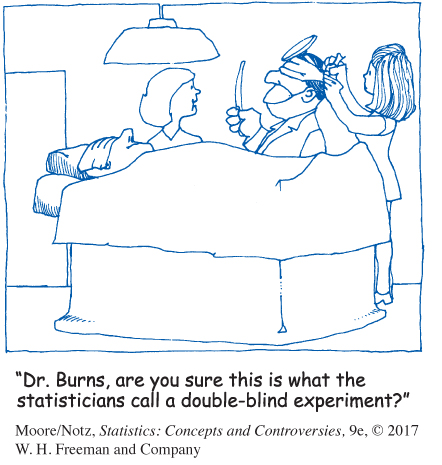

Because the placebo effect is so strong, it would be foolish to tell subjects in a medical experiment whether they are receiving a new drug or a placebo. Knowing that they are getting “just a placebo” might weaken the placebo effect and bias the experiment in favor of the other treatments. It is also foolish to tell doctors and other medical personnel what treatment each subject is receiving. If they know that a subject is getting “just a placebo,” they may expect less than if they know the subject is receiving a promising experimental drug. Doctors’ expectations change how they interact with patients and even the way they diagnose a patient’s condition. Whenever possible, experiments with human subjects should be double-blind.

Double-blind experiments

In a double-blind experiment, neither the subjects nor the people who work with them know which treatment each subject is receiving.

Until the study ends and the results are in, only the study’s statistician knows for sure. Reports in medical journals regularly begin with words like these, from a study of a flu vaccine given as a nose spray: “This study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Participants were enrolled from 13 sites across the continental United States between mid-September and mid-November 1997.” Doctors are expected to know what “randomized,” “double-blind,” and “placebo-controlled” mean. Now you also know.