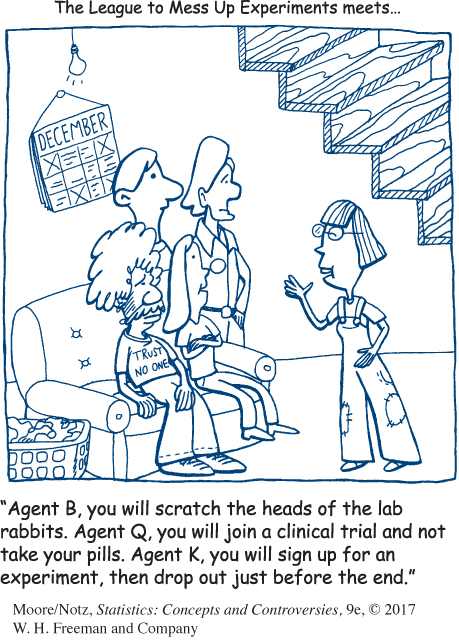

Refusals, nonadherers, and dropouts

Sample surveys suffer from nonresponse due to failure to contact some people selected for the sample and the refusal of others to participate. Experiments with human subjects suffer from similar problems.

EXAMPLE 3 Minorities in clinical trials

Refusal to participate is a serious problem for medical experiments on treatments for major diseases such as cancer. As in the case of samples, bias can result if those who refuse are systematically different from those who cooperate.

Clinical trials are medical experiments involving human subjects. Minorities, women, the poor, and the elderly have long been underrepresented in clinical trials. In many cases, they weren’t asked. The law now requires representation of women and minorities, and data show that most clinical trials now have fair representation. But refusals remain a problem. Minorities, especially blacks, are more likely to refuse to participate. The government’s Office of Minority Health says, “Though recent studies have shown that African Americans have increasingly positive attitudes toward cancer medical research, several studies corroborate that they are still cynical about clinical trials. A major impediment for lack of participation is a lack of trust in the medical establishment.” Some remedies for lack of trust are complete and clear information about the experiment, insurance coverage for experimental treatments, participation of black researchers, and cooperation with doctors and health organizations in black communities.

Subjects who participate but don’t follow the experimental treatment, called nonadherers, can also cause bias. AIDS patients who participate in trials of a new drug sometimes take other treatments on their own, for example. In addition, some AIDS subjects have their medication tested and drop out or add other medications if they were not assigned to the new drug. This may bias the trial against the new drug.

Experiments that continue over an extended period of time also suffer dropouts, subjects who begin the experiment but do not complete it. If the reasons for dropping out are unrelated to the experimental treatments, no harm is done other than reducing the number of subjects. If subjects drop out because of their reaction to one of the treatments, bias can result.

EXAMPLE 4 Dropouts in a medical study

Orlistat is a drug that may help reduce obesity by preventing absorption of fat from the foods we eat. As usual, the drug was compared with a placebo in a double-blind randomized trial. Here’s what happened.

The subjects were 1187 obese subjects. They were given a placebo for four weeks, and the subjects who wouldn’t take a pill regularly were dropped. This addressed the problem of nonadherers. There were 892 subjects left. These subjects were randomly assigned to Orlistat or a placebo, along with a weight-loss diet. After a year devoted to losing weight, 576 subjects were still participating. On the average, the Orlistat group lost 3.15 kilograms (about 7 pounds) more than the placebo group. The study continued for another year, now emphasizing maintaining the weight loss from the first year. At the end of the second year, 403 subjects were left. That’s only 45% of the 892 who were randomized. Orlistat again beat the placebo, reducing the weight regained by an average of 2.25 kilograms (about 5 pounds).

Can we trust the results when so many subjects dropped out? The overall dropout rates were similar in the two groups: 54% of the subjects taking Orlistat and 57% of those in the placebo group dropped out. Were dropouts related to the treatments? Placebo subjects in weight-loss experiments often drop out because they aren’t losing weight. This would bias the study against Orlistat because the subjects in the placebo group at the end may be those who could lose weight just by following a diet. The researchers looked carefully at the data available for subjects who dropped out. Dropouts from both groups had lost less weight than those who stayed, but careful statistical study suggested that there was little bias. Perhaps so, but the results aren’t as clean as our first look at experiments promised.