Measurements, accurate and inaccurate

Using a bathroom scale to measure your weight is valid. If your scale is like many commonly used ones, however, the measurement may not be very accurate. It measures weight, but it may not give the true weight. Let’s say that originally your scale always read 3 pounds too high, so

measured weight = true weight + 3 pounds

If that is the whole story, the scale will always give the same reading for the same true weight. Most scales vary a bit—they don’t always give the same reading when you step off and step right back on. Your scale now is somewhat old and rusty. It still always reads 3 pounds too high because its aim is off, but now it is also erratic, so readings deviate from 3 pounds. This morning it sticks a bit and reads 1 pound too low for that reason. So the reading is

measured weight = true weight + 3 pounds − 1 pound

When you step off and step right back on, the scale sticks in a different spot that makes it read 1 pound too high. The reading you get is now

measured weight = true weight + 3 pounds + 1 pound

You don’t like the fact that this second reading is higher than the first, so you again step off and step right back on. The scale again sticks in a different spot and you get the reading

measured weight = true weight + 3 pounds − 1.5 pounds

If you have nothing better to do than keep stepping on and off the scale, you will keep getting different readings. They center on a reading 3 pounds too high, but they vary about that center.

Your scale has two kinds of errors. If it didn’t stick, the scale would always read 3 pounds high. That is true every time anyone steps on the scale. This systematic error that occurs every time we make a measurement is called bias. Your scale also sticks—but how much this changes the reading differs every time someone steps on the scale. Sometimes stickiness pushes the scale reading up; sometimes it pulls it down. The result is that the scale weighs 3 pounds too high on the average, but its reading varies when we weigh the same thing repeatedly. We can’t predict the error due to stickiness, so we call it random error.

Errors in measurement

We can think about errors in measurement this way:

measured value = true value + bias + random error

A measurement process has bias if it systematically tends to overstate or understate the true value of the property it measures.

A measurement process has random error if repeated measurements on the same individual give different results. If the random error is small, we say the measurement is reliable.

To determine if the random error is small, we can use a quantity called the variance. The variance of n repeated measurements on the same individual is computed as follows:

1. Find the arithmetic average of these n measurements.

2. Compute the difference between each observation and the arithmetic average and square each of these differences.

3. Average the squared differences by dividing their sum by n − 1. This average squared difference is the variance.

A reliable measurement process will have a small variance.

For the three measurements on our sticky scale, suppose that our true weight is 130 pounds. Then the three measurements are

130 + 3 − 1 = 132 pounds

130 + 3 + 1 = 134 pounds

130 + 3 − 1.5 = 131.5 pounds

The average of these three measurements is

(132 + 134 + 131.5)/3 = 397.5/3 = 132.5 pounds

The differences between each measurement and the average are

132 − 132.5 = −0.5

134 − 132.5 = 1.5

131.5 − 132.5 = −1

The sum of the squares of these differences is

(−0.5)2 + (1.5)2 + (−1)2 = 0.25 + 2.25 + 1 = 3.5

and so the variance of these random errors is

3.5/(3 − 1) = 1.75

In the text box, we said that a reliable measurement process will have a small variance. In this example, the variance of 1.75 is quite small relative to the actual weights, so it appears that the measurement process using this scale is reliable.

A scale that always reads the same when it weighs the same item is perfectly reliable even if it is biased. For such a scale, the variance of the measurements will be 0.

Reliability says only that the result is dependable. Bias means that in repeated measurements the tendency is to systematically either overstate or understate the true value. It does not necessarily mean that every measurement overstates or understates the true value. Bias and lack of reliability are different kinds of error. And don’t confuse reliability with validity just because both sound like good qualities. Using a scale to measure weight is valid even if the scale is not reliable.

Here’s an example of a measurement that is reliable but not valid.

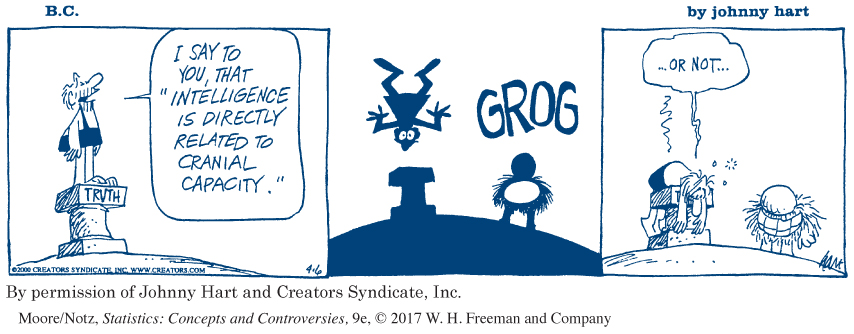

EXAMPLE 8 Do big skulls house smart brains?

In the mid-nineteenth century, it was thought that measuring the volume of a human skull would measure the intelligence of the skull’s owner. It was difficult to measure a skull’s volume reliably, even after it was no longer attached to its owner. Paul Broca, a professor of surgery, showed that filling a skull with small lead shot, then pouring out the shot and weighing it, gave quite reliable measurements of the skull’s volume. These accurate measurements do not, however, give a valid measure of intelligence. Skull volume turned out to have no relation to intelligence or achievement.

NOW IT’S YOUR TURN

Question 8.2

8.2 The most popular burger joint. If you live in the United States, you may have heard your friends debate whether In-N-Out Burger or Five Guys Burgers and Fries has the better hamburger. According to the Consumer Reports National Research Center, In-N-Out Burger ranked first in both 2011 and 2014. Five Guys Burgers and Fries ranked third in 2011 but seventh in 2014. Is this proof that In-N-Out has better burgers? Do you think these ratings are biased, unreliable, or both? Explain your answer.

8.2 Although In-N-Out Burger was rated first both times, there may be some reliability concerns since the same restaurant (Five Guys Burger and Fries) received drastically different ratings between 2011 (third) and 2014 (seventh).