10.1 How Can Intelligence Be Measured?

Few things are more dangerous than a man with a mission. In the 1920s, psychologist Henry Goddard administered intelligence tests to arriving immigrants at Ellis Island and concluded that the overwhelming majority of Jews, Hungarians, Italians, and Russians were “feebleminded.” Goddard also used his tests to identify feebleminded American families (whom, he claimed, were largely responsible for the nation’s social problems) and suggested that the government should segregate them in isolated colonies and “take away from these people the power of procreation” (Goddard, 1913, p. 107). The United States subsequently passed laws restricting the immigration of people from Southern and Eastern Europe, and 27 states passed laws requiring the sterilization of “mental defectives.”

397

From Goddard’s day to our own, intelligence tests have been used to rationalize prejudice and discrimination against people of different races, religions, and nationalities. Although intelligence testing has achieved many notable successes, its history is marred by more than its share of fraud and disgrace (Chorover, 1980; Lewontin, Rose, & Kamin, 1984). The fact that intelligence tests have occasionally been used to further detestable ends is especially ironic because, as you are about to see, such tests were originally developed for the most noble of purposes: to help underprivileged children succeed in school.

The Intelligence Quotient

Why were intelligence tests originally developed?

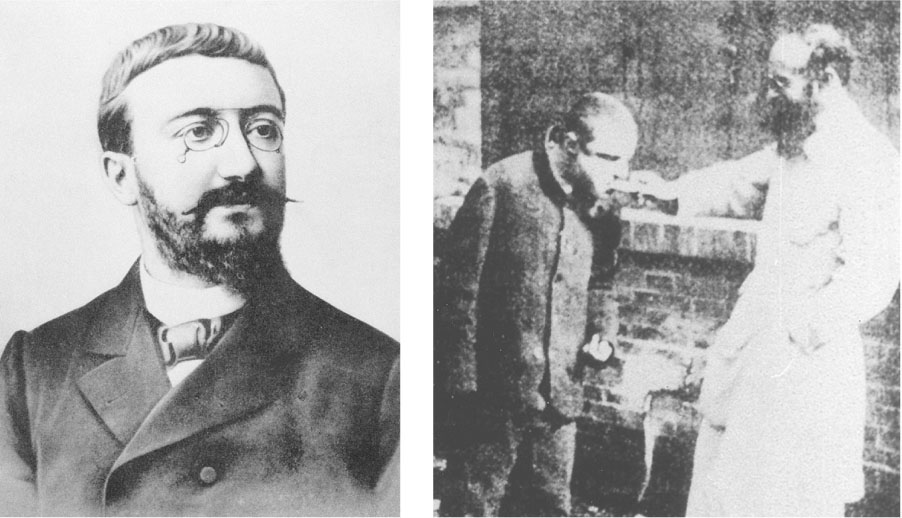

At the end of the 19th century, France instituted a sweeping set of education reforms that made a primary school education available to children of every social class, and suddenly French classrooms were filled with a diverse mix of children who differed dramatically in their readiness to learn. The French government called on Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon to create a test that would allow educators to develop remedial programs for those children who lagged behind their peers (Siegler, 1992). “Before these children could be educated,” Binet (1909) wrote, “they had to be selected. How could this be done?”

Binet and Simon worried that if teachers were allowed to do the selecting, then the remedial classrooms would be filled with poor children, and that if parents were allowed to do the selecting, then the remedial classrooms would be empty. So they set out to develop an objective test that would provide an unbiased measure of a child’s ability. They began, sensibly enough, by looking for tasks that the best students in a class could perform and that the worst students could not–in other words, tasks that could distinguish the best and worst students and thus predict a future child’s success in school. The tasks they tried included solving logic problems, remembering words, copying pictures, distinguishing edible and inedible foods, making rhymes, and answering questions such as, “When anyone has offended you and asks you to excuse him, what ought you to do?” Binet and Simon settled on 30 of these tasks and assembled them into a test that they claimed could measure a child’s “natural intelligence.” What did they mean by that phrase?

ARCHIVES OF THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGY, THE UNIVERSITY OF AKRON

We here separate natural intelligence and instruction…by disregarding, insofar as possible, the degree of instruction which the subject possesses…. We give him nothing to read, nothing to write, and submit him to no test in which he might succeed by means of rote learning. In fact, we do not even notice his inability to read if a case occurs. It is simply the level of his natural intelligence that is taken into account. (Binet, 1905)

Binet and Simon designed their test to measure a child’s aptitude for learning independent of the child’s prior educational achievement, and it was in this sense that they called theirs a test of natural intelligence. They suggested that teachers could use their test to estimate a particular child’s “mental level” simply by computing the average test score of many children in different age groups and then finding the age group whose average test score was most like that of the particular child’s. For example, a child who was 10 years old but whose score was about the same as the score of the average 8-

398

How do the two kinds of intelligence quotients differ?

German psychologist William Stern (1914) suggested that this mental level could be thought of as a child’s mental age and that the best way to determine whether a child was developing normally was to examine the ratio of the child’s mental age to the child’s physical age. American psychologist Lewis Terman (1916) formalized this comparison by developing a statistic called the intelligence quotient or IQ score. There are two ways to compute an IQ score, each of which has a unique problem.

Ratio IQ is a statistic obtained by dividing a person’s mental age by the person’s physical age and then multiplying the quotient by 100. According to this formula, a 10-

Ratio IQ is a statistic obtained by dividing a person’s mental age by the person’s physical age and then multiplying the quotient by 100. According to this formula, a 10-year- old child whose test score was about the same as the average 10- year- old child’s test score would have a ratio IQ of 100 because (10/10) × 100 = 100. But a 10- year- old child whose test score was about the same as the average 8- year- old child’s test score would have a ratio IQ of 80 because (8/10) × 100 = 80. So what’s the problem? Well, a 7- year- old who performs like the average 14- year- old has a ratio IQ of 200, and that high score seems reasonable because a 7- year- old who can do algebra is obviously pretty smart. But a 20- year- old who performs like the average 40- year- old will also have a ratio IQ of 200, and that doesn’t seem very reasonable at all.  Deviation IQ is a statistic obtained by dividing a person’s test score by the average test score of people in the same age group and then multiplying the quotient by 100. According to this formula, a person who scored the same as the average person his or her age would have a deviation IQ of 100. The deviation IQ overcomes the problem with the ratio IQ inasmuch as a 20-

Deviation IQ is a statistic obtained by dividing a person’s test score by the average test score of people in the same age group and then multiplying the quotient by 100. According to this formula, a person who scored the same as the average person his or her age would have a deviation IQ of 100. The deviation IQ overcomes the problem with the ratio IQ inasmuch as a 20-year- old who scores like the average 40- year- old is not mistakenly labeled a genius. Alas, the deviation IQ has a different problem: It does not allow us to compare people of different ages. A 5- year- old and a 65- year- old might both have a deviation IQ of 100 because they both scored the same as their average peer, but that does not mean that the 5- year- old and 65- year- old are equally intelligent. Which one is smarter? We can’t tell by comparing deviation IQs.

Each of the methods for computing IQ has a problem–but luckily, each has a different problem so they can be used in combination. Psychologists typically compute ratio IQ when testing children and compute deviation IQ when testing adults.

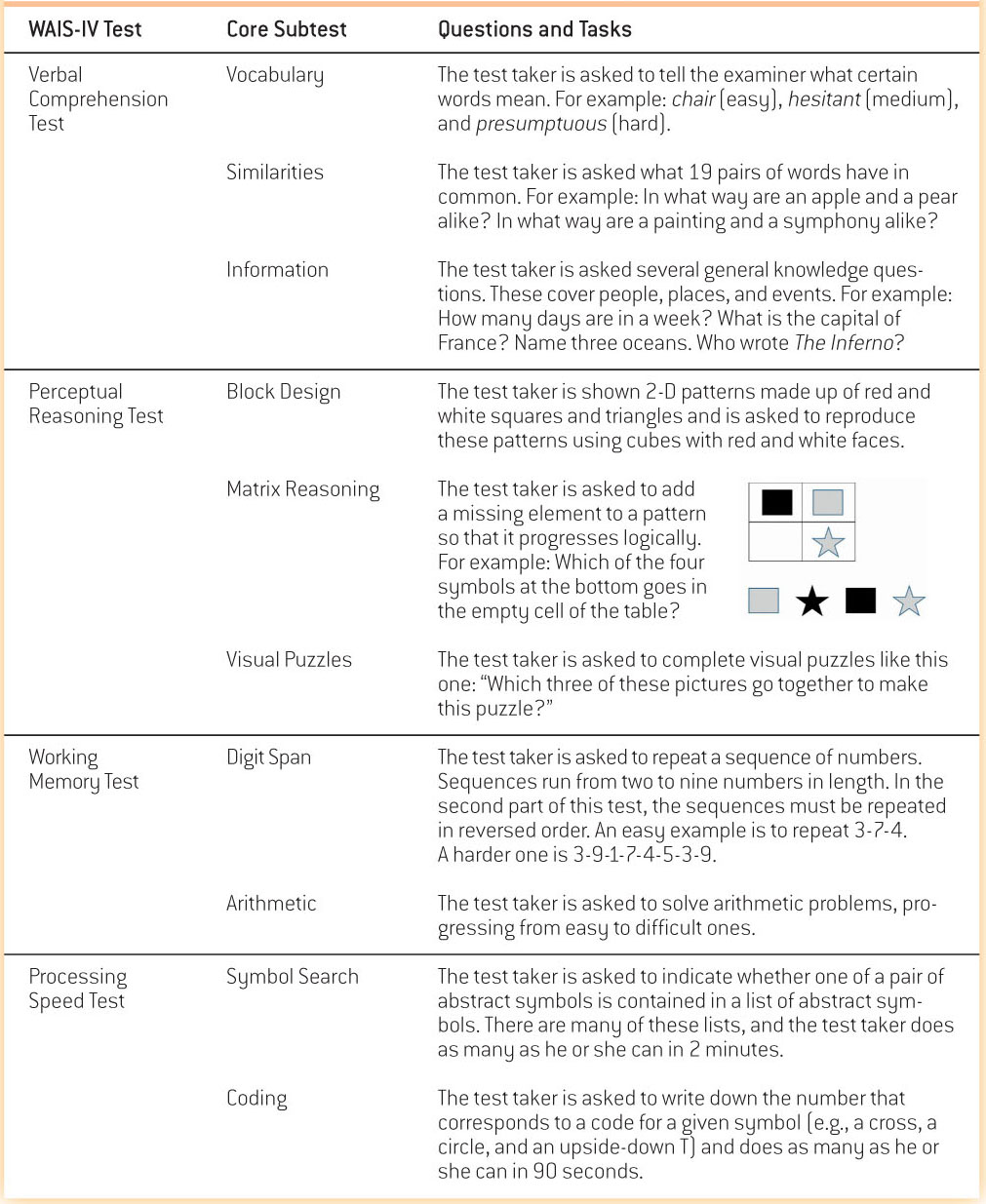

The Intelligence Test

Most modern intelligence tests have their roots in the test developed more than a century ago by Binet and Simon. For instance, the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scale is based on Binet and Simon’s original test and was initially updated by Lewis Terman and his colleagues at Stanford University. Probably the most widely used modern intelligence test is the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), named after its originator, psychologist David Wechsler. Like Binet and Simon’s original test, it measures intelligence by asking respondents to answer questions and solve problems. Respondents are required to see similarities and differences between ideas and objects, to draw inferences from evidence, to work out and apply rules, to remember and manipulate material, to construct shapes, to articulate the meaning of words, to recall general knowledge, to explain practical actions in everyday life, to use numbers, to attend to details, and so forth. In the spirit of Binet and Simon’s early test, none of the tests require writing words. Some sample problems from the WAIS are shown in TABLE 10.1.

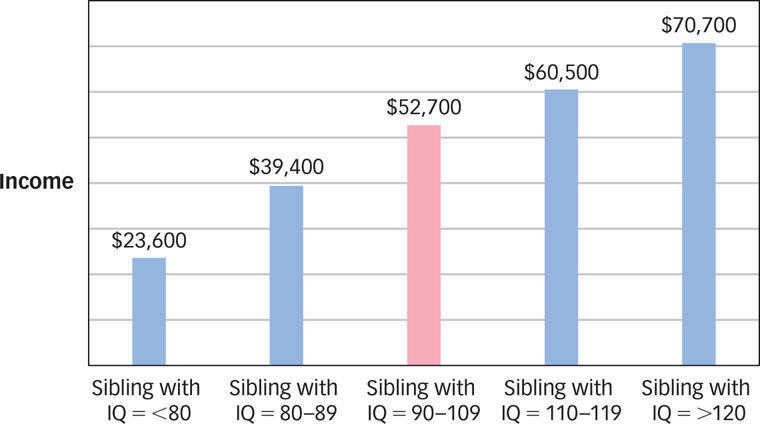

These sample problems may look to you like fun and games (perhaps minus the fun part), but decades of research show that a person’s performance on tests like the WAIS predict a wide variety of important life outcomes (Deary, Batty, & Gale, 2008; Deary, Batty, Pattie, & Gale, 2008; Der, Batty, & Deary, 2009; Gottfredson & Deary, 2004; Leon et al., 2009; Richards et al., 2009; Rushton & Templer, 2009; Whalley & Deary, 2001). For example, intelligence test scores are excellent predictors of income. One study compared siblings who had significantly different IQs and found that the less intelligent sibling earned roughly half of what the more intelligent sibling earned over the course of their lifetimes (Murray, 2002; see FIGURE 10.1).

Figure 10.1: Income and Intelligence among Siblings This graph shows the average annual salary of a person who has an IQ of 90–109 (shown in pink) and of his or her siblings who have higher or lower IQs (shown in blue).

Figure 10.1: Income and Intelligence among Siblings This graph shows the average annual salary of a person who has an IQ of 90–109 (shown in pink) and of his or her siblings who have higher or lower IQs (shown in blue).

What important life outcomes do intelligence test scores predict?

399

One reason for this is that intelligent people have a variety of traits that promote economic success. For example, they are more patient, they are better at calculating risk, and they are better at predicting how other people will act and how they should respond (Burks et al., 2009). But the main reason why intelligent people earn much more money than their less intelligent counterparts (or siblings!) is that they get more education (Deary et al., 2005; Nyborg & Jensen, 2001). In fact, a person’s IQ is a better predictor of the amount of education he or she will receive than is the person’s social class (Deary, 2012; Deary et al., 2005). Intelligent people spend more time in school and perform better when they’re there: The correlation between IQ and academic performance is roughly r = .50 across a wide range of people and situations. This continues after school ends. Intelligent people perform so much better at their jobs (Hunter & Hunter, 1984) that one pair of researchers concluded that “for hiring employees without previous experience in the job, the most valid measure of future performance and learning is general mental ability” (Schmidt & Hunter, 1998, p. 262; see the Real World box).

400

THE REAL WORLD: Look Smart

Your interview is in 30 minutes. You’ve checked your hair twice, eaten your weight in breath mints, combed your résumé for typos, and rehearsed your answers to all the standard questions. Now you have to dazzle them with your intelligence whether you’ve got it or not. Because intelligence is one of the most valued of all human traits, we are often in the business of trying to make others think we’re smart regardless of whether that’s true. So we make clever jokes and drop the names of some of the longer books we’ve read in the hope that prospective employers, prospective dates, prospective customers, and prospective in-

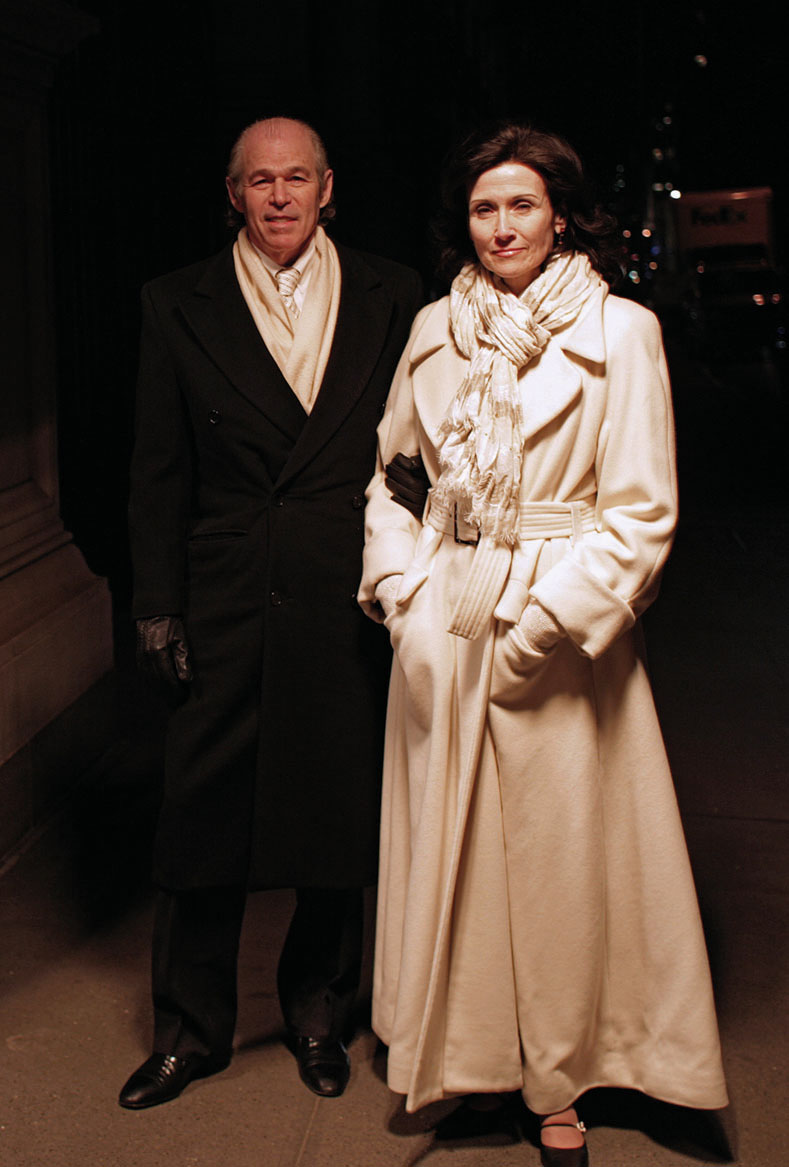

But are we doing the right things, and if so, are we getting the credit we deserve? Research shows that ordinary people are, in fact, reasonably good judges of other people’s intelligence (Borkenau & Liebler, 1995). For example, observers can look at a pair of photographs and reliably determine which of the two people in them is smarter (Zebrowitz et al., 2002). When observers watch 1-

People base their judgments of intelligence on a wide range of cues, from physical features (being tall and attractive) to dress (being well groomed and wearing glasses) to behavior (walking and talking quickly). And yet, none of these cues is actually a reliable indicator of a person’s intelligence. The reason why people are such good judges of intelligence is that in addition to all these useless cues, they also take into account one very useful cue: eye gaze. As it turns out, intelligent people hold the gaze of their conversation partners both when they are speaking and when they are listening, and observers know this, which is what enables them to estimate a person’s intelligence accurately, despite their mythical beliefs about the informational value of spectacles and neckties (Murphy et al., 2003). All of this is especially true when the observers are women (who tend to be better judges of intelligence) and the people being observed are men (whose intelligence tends to be easier to judge).

The bottom line? Breath mints are fine and a little gel on the cowlick certainly can’t hurt, but when you get to the interview, don’t forget to stare.

Intelligent people aren’t just wealthier, they are healthier as well. Researchers who have followed millions of people over decades have found a strong correlation between intelligence and both health and longevity. Intelligent people are less likely to smoke and drink alcohol, and are more likely to exercise and eat well (Batty et al., 2007; Weiser et al., 2010). Not surprisingly, they also live longer. In fact, every 15 point increase in a young person’s IQ is associated with a 24% decrease in his or her ultimate risk of death from a wide variety of causes, including cardiovascular disease, suicide, homicide, and accidents (Calvin et al., 2010). Health and wealth are related, of course, and some data suggest that intelligence promotes longevity by allowing people to succeed in school, which allows them to get better jobs, which allows them to earn more money, which allows them to avoid illnesses such as cardiovascular disease (Deary, Weiss, & Batty, 2011). However it happens, the bottom line is clear: Intelligence matters.

401

Intelligence is a mental ability that enables people to direct their thinking, adapt to their circumstances, and learn from their experiences.

Intelligence is a mental ability that enables people to direct their thinking, adapt to their circumstances, and learn from their experiences. Intelligence tests produce a score known as an intelligence quotient or IQ. Ratio IQ is the ratio of a person’s mental to physical age and deviation IQ is the deviation of a person’s test score from the average score of his or her peers.

Intelligence tests produce a score known as an intelligence quotient or IQ. Ratio IQ is the ratio of a person’s mental to physical age and deviation IQ is the deviation of a person’s test score from the average score of his or her peers. Intelligence test scores predict a variety of important life outcomes, such as scholastic performance, job performance, health, and wealth.

Intelligence test scores predict a variety of important life outcomes, such as scholastic performance, job performance, health, and wealth.