11.2 Infancy and Childhood: Becoming a Person

Newborns may appear to be capable of little more than squalling and squirming, but in the last decade, researchers have discovered that they are much more sophisticated than they appear. Infancy is the stage of development that begins at birth and lasts between 18 and 24 months, and as you will see, a lot more happens during this stage than meets the untrained eye.

Perceptual and Motor Development

What do newborns see?

New parents like to stand around the crib and make goofy faces at the baby because they think the baby will be amused. In fact, newborns have a rather limited range of vision. The level of detail that a newborn can see at a distance of 20 feet is roughly equivalent to the level of detail that an adult can see at 600 feet (Banks & Salapatek, 1983), which is to say that they are missing out on a lot of the cribside shenanigans. On the other hand, when stimuli are 8 to 12 inches away (about the distance between a nursing infant’s eyes and its mother’s face), newborns are visually quite responsive. How do we know what newborns are seeing? In one study, newborns were shown a circle with diagonal stripes over and over again. The infants stared a lot at first, and then less and less on each subsequent presentation. Recall from the Learning chapter that habituation is the tendency for organisms to respond less intensely to a stimulus as the frequency of exposure to that stimulus increases, and infants habituate just like the rest of us do. So what happened when the researchers rotated the circle 90°? The newborns once again stared intently, indicating that they had noticed the change in the circle’s orientation (Slater, Morison, & Somers, 1988).

Why are infants born with reflexes?

Newborns are especially attentive to social stimuli. For example, newborns in one study were shown a circle, a circle with scrambled facial features, or a circle with a regular face. When the circle was moved across their fields of vision, the newborns tracked the circle by moving their heads and eyes—

Although infants can use their eyes right away, they must spend considerably more time learning how to use their other parts. Motor Development is the emergence of the ability to execute physical actions such as reaching, grasping, crawling, and walking. Infants are born with a small set of reflexes, which are specific patterns of motor response that are triggered by specific patterns of sensory stimulation. For example, the rooting reflex is the tendency for infants to move their mouths toward any object that touches their cheek, and the sucking reflex is the tendency to suck any object that enters their mouths. These two reflexes allow newborns to find their mother’s nipple and begin feeding—

In what order do infants learn to use parts of their bodies?

432

The development of these more sophisticated behaviors tends to obey two general rules. The first is the cephalocaudal rule (or the “top-

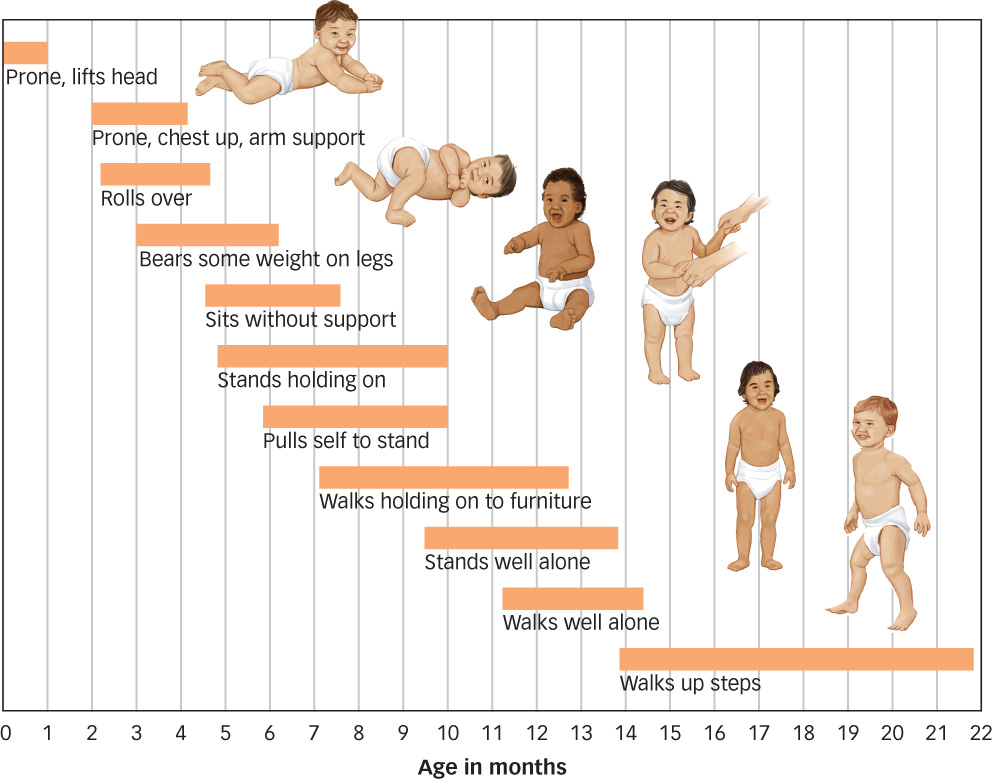

Figure 11.2: Motor Development Infants learn to control their bodies from head to feet and from center to periphery. These skills do not emerge on a strict timetable, but they do emerge in a strict sequence.

Figure 11.2: Motor Development Infants learn to control their bodies from head to feet and from center to periphery. These skills do not emerge on a strict timetable, but they do emerge in a strict sequence.

Motor skills generally emerge in an orderly sequence but not on a strict timetable. Rather, the timing of these skills is influenced by many factors, such as the infant’s incentive for reaching, body weight, muscular development, and general level of activity. In one study, infants who had visually stimulating mobiles hanging above their cribs began reaching for objects 6 weeks earlier than infants who did not (White & Held, 1966). Furthermore, different infants seem to acquire the same skill in different ways. By closely following the development of four infants, one study examined how children learn to reach (Thelen et al., 1993). Two of the infants were especially energetic and initially produced large circular movements of both arms. To reach accurately, these infants had to learn to dampen these large circular movements by holding their arms rigid at the elbow and swiping at an object. The other two infants were less energetic and did not produce large, circular movements. Thus, their first step in learning to reach involved learning to lift their arms against the force of gravity and extend them forward. Detailed observations such as these suggest that, although most infants learn how to reach, different infants learn in different ways (Adolph & Avoilio, 2000).

433

Cognitive Development

What are the three essential tasks of cognitive development?

Infants can hear and see and move their bodies. But can they think? In the first half of the 20th century, a Swiss biologist named Jean Piaget became interested in this question. He noticed that when confronted with difficult problems (Does the big glass have more liquid in it than the small glass? Can Billy see what you see?), children of the same age made roughly the same mistakes. And as they aged, they stopped making these mistakes at about the same time. This led Piaget to suggest that children move through discrete stages of cognitive development, which is the emergence of the ability to think and understand. Between infancy and adulthood, children must come to understand three important things: (a) how the physical world works, (b) how their minds represent the world, and (c) how other minds represent the world. Let’s see how children accomplish these three essential tasks.

Discovering the World

| Stage | Characteristic |

|---|---|

|

Sensorimotor (Birth–2 years) |

Infant experiences world through movement and senses, develops schemas, begins to act intentionally, and shows evidence of understanding object permanence. |

|

Preoperational (2–6 years) |

Child acquires motor skills but does not understand conservation of physical properties. Child begins this stage by thinking egocentrically but ends with a basic understanding of other minds. |

|

Concrete operational (6–11 years) |

Child can think logically about physical objects and events and understands conservation of physical properties. |

|

Formal operational (11 years and up) |

Child can think logically about abstract propositions and hypotheticals. |

Piaget (1954) suggested that cognitive development occurs in four stages: the sensorimotor stage, the preoperational stage, the concrete operational stage, and the formal operational stage (see TABLE 11.1). The sensorimotor stage is a period of development that begins at birth and lasts through infancy. As the word sensorimotor suggests, infants at this stage are mainly busy using their ability to sense and their ability to move to acquire information about the world. By actively exploring their environments with their eyes, mouths, and fingers, infants begin to construct schemas, which are theories about the way the world works.

What happens at the sensorimotor stage?

As every scientist knows, the key advantage of having a theory is that one can use it to predict and control what will happen in novel situations. If an infant learns that tugging at a stuffed animal causes the toy to come closer, then that observation is incorporated into the infant’s theory about how physical objects behave, and the infant can later use that theory when he or she wants a different object to come closer, such as a rattle or a ball. Piaget called this assimilation, which happens when infants apply their schemas in novel situations. Of course, if the infant tugs the tail of the family cat, the cat is likely to sprint in the opposite direction. Infants’ theories about the world (“Things come closer if I pull them”) are occasionally disconfirmed, and so infants must occasionally adjust their schemas in light of their new experiences (“Aha! Only inanimate things come closer when I pull them”). Piaget called this accommodation, which happens when infants revise their schemas in light of new information.

When do children acquire a theory of object permanence?

434

What kinds of schemas do infants develop, apply, and adjust? Piaget suggested that infants lack some very basic understandings about the physical world and therefore must acquire them through experience. For example, when you put your shoes in the closet, you know that they exist even after you close the closet door, and you would be rather surprised if you opened the door a moment later and found the closet empty. But according to Piaget, this wouldn’t surprise an infant because infants do not have a theory of object permanence, which is the belief that objects exist even when they are not visible. Piaget noted that in the first few months of life, infants act as though objects stop existing the moment they are out of sight. For instance, he observed that a 2-

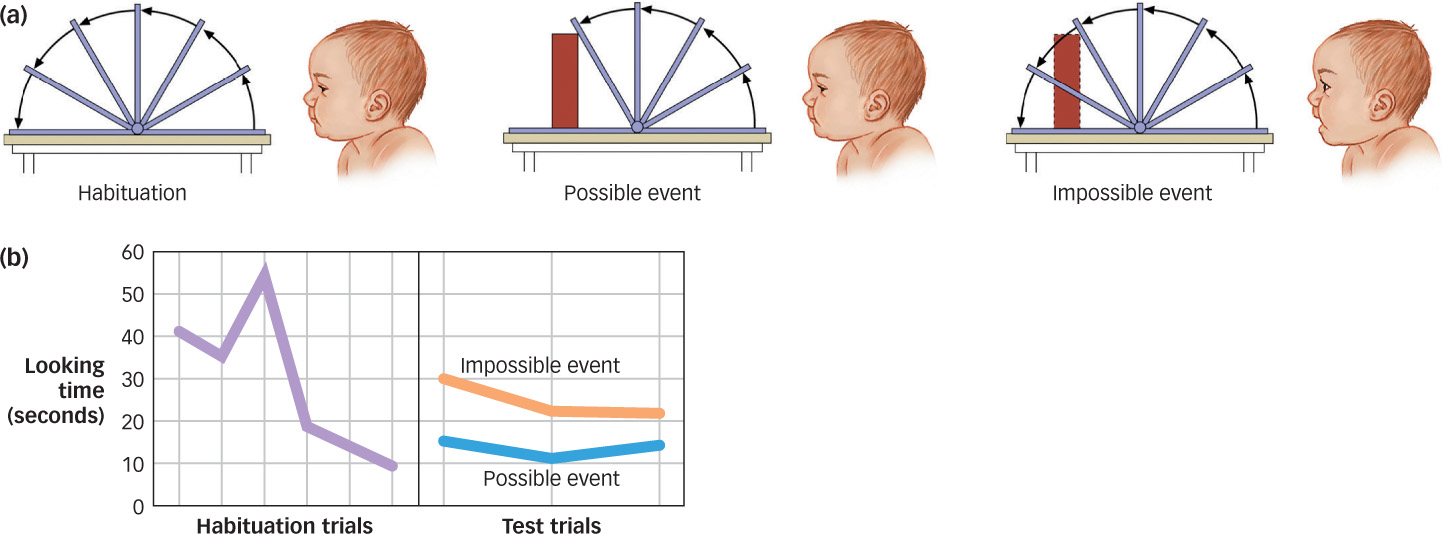

Was Piaget right? As a general rule, when infants demonstrate an ability, then they definitely have it, but when they fail to demonstrate an ability, they may lack the ability or the test may not be sensitive enough to reveal it. Modern research shows that when other tests are used, infants can demonstrate their sense of object permanence much earlier than Piaget realized (Shinskey & Munakata, 2005). For instance, in one study, infants were shown a miniature drawbridge that flipped up and down (see FIGURE 11.3). Once the infants got used to this, they watched as a box was placed behind the drawbridge—

Figure 11.3: The Impossible Event (a) In the habituation trials, infants watched a drawbridge flip back and forth with nothing in its path until they grew bored. Then a box was placed behind the drawbridge and the infants were shown one of two events: In the possible event, the box kept the drawbridge from flipping all the way over; in the impossible event, it did not. (b) The graph shows the infants’ looking time during the habituation and the test trials. During the test trials, their interest was reawakened by the impossible event but not by the possible event (Baillargeon, Spelke, & Wasserman, 1985).

Figure 11.3: The Impossible Event (a) In the habituation trials, infants watched a drawbridge flip back and forth with nothing in its path until they grew bored. Then a box was placed behind the drawbridge and the infants were shown one of two events: In the possible event, the box kept the drawbridge from flipping all the way over; in the impossible event, it did not. (b) The graph shows the infants’ looking time during the habituation and the test trials. During the test trials, their interest was reawakened by the impossible event but not by the possible event (Baillargeon, Spelke, & Wasserman, 1985).

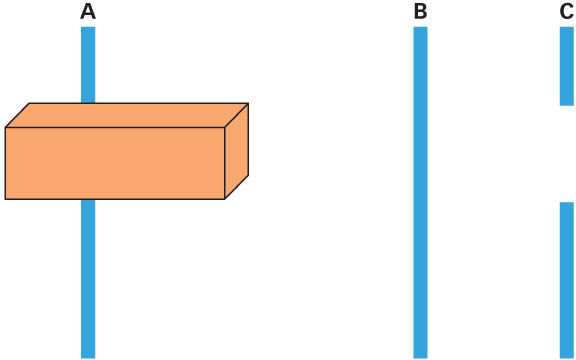

Figure 11.4: Object Permanence Do infants see line A as continuous or broken? Infants who are shown line A are subsequently more interested when they are shown line C than line B. This indicates that they consider C more novel than B, which suggests that the infants saw line A as continuous and not broken (Kellman & Spelke, 1983).

Figure 11.4: Object Permanence Do infants see line A as continuous or broken? Infants who are shown line A are subsequently more interested when they are shown line C than line B. This indicates that they consider C more novel than B, which suggests that the infants saw line A as continuous and not broken (Kellman & Spelke, 1983).

Studies such as these suggest that infants do indeed have some understanding of object permanence by the time they are just 4 months old. For example, what do infants see when they look at the line labeled A in FIGURE 11.4? Adults see a continuous blue line that is being obstructed by the solid orange block in front of it. Do infants see line A as continuous and obstructed, or do they see it as two blue objects on either side of an orange object? Studies show that when infants are allowed to become familiar with line A, they are subsequently more surprised by line C than by line B, despite the fact that line C actually looks more like line A than does line B (Kellman & Spelke, 1983). This suggests that infants see line A as a continuous line. Infants clearly do not think of the world only in terms of its visible parts, and at a very early age they seem to “know” that objects continue to exist even when they are out of sight (Wang & Baillargeon, 2008).

435

Piaget (1927/1977, p. 199) wrote: “The child’s first year of life is unfortunately still an abyss of mysteries for the psychologist. If only we could know what is going on in a baby’s mind while observing him in action, we could certainly understand everything there is to psychology.” Although the mystery of the infant mind is still far from solved, it is no longer an abyss. Research has taught us a great deal about what infants do and do not know, and the general conclusion is that they know much more than Piaget (or their parents) ever suspected (Gopnik, 2012).

Discovering the Mind

The long period following infancy is called childhood, which is the period that begins at about 18 to 24 months and lasts until about 11 to 14 years. According to Piaget, children enter childhood at one stage of cognitive development and leave at another. They enter in the preoperational stage, which is the stage of cognitive development that begins at about 2 years and ends at about 6 years, during which children develop a preliminary understanding of the physical world. They exit at the concrete operational stage, which is the stage of cognitive development that begins at about 6 years and ends at about 11 years, during which children learn how actions or “operations” can transform the “concrete” objects of the physical world.

HOT SCIENCE: A Statistician in the Crib

A magician asks you to shuffle a deck of cards and then name your favorite. He then dons a blindfold, reaches out his hand, and pulls your favorite card from the deck. You are astonished—

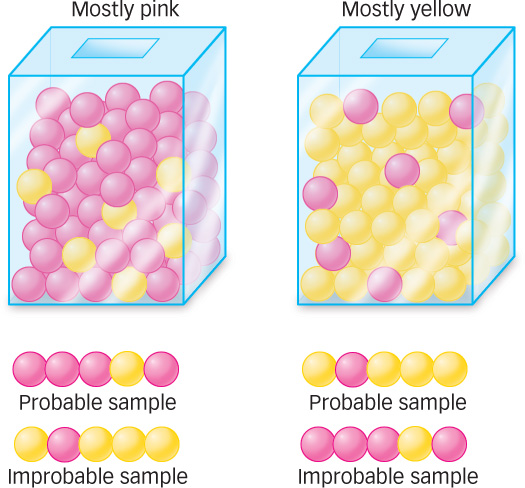

Would that trick astonish an infant? That’s pretty hard to imagine. After all, to appreciate the trick, one has to understand a basic rule of statistics, namely, that random samples look roughly like the populations from which they are drawn. But recent research (Denison, Reed, & Xu, 2013) suggests that infants as young as 24 weeks understand just that.

In one study, researchers showed infants two boxes: one had mostly pink balls and just a few yellows; the other had mostly yellow balls with a few pinks. The infants then watched as an experimenter closed her eyes and reached into the mostly pink box, pulled out some balls, and deposited them in a little container in front of the infant. Sometimes she deposited four pinks and a yellow, and sometimes she deposited four yellows and pink. What did the infants do?

When the experimenter pulled mainly pink balls from a mainly pink box, the infants glanced and then looked away. But when she pulled mainly yellow balls from a mainly pink box, they stared like bystanders at a train wreck. The fact that infants looked longer at the improbable sample than at the probable sample suggests that they found the former more astonishing; in other words, they had some basic understanding of how random sampling works.

This study—

What distinguishes the preoperational and concrete operational stages?

436

The difference between these stages is nicely illustrated by one of Piaget’s clever experiments in which he showed children a row of cups and asked them to place an egg in each. Preoperational children were able to do this, and afterward they readily agreed that there were just as many eggs as there were cups. Then Piaget removed the eggs and spread them out in a long line that extended beyond the row of cups. Preoperational children incorrectly claimed that there were now more eggs than cups, pointing out that the row of eggs was longer than the row of cups and hence there must be more of them. Concrete operational children, on the other hand, correctly reported that the number of eggs did not change when they were spread out in a longer line. They understood that quantity is a property of a set of concrete objects that does not change when an operation such as spreading out alters the set’s appearance (Piaget, 1954). Piaget called the child’s insight conservation, which is the notion that the quantitative properties of an object are invariant despite changes in the object’s appearance.

Why don’t preoperational children seem to grasp the notion of conservation? Piaget suggested that children have several tendencies that explain this mistake. For instance, centration is the tendency to focus on just one property of an object to the exclusion of all others. Whereas adults can consider several properties at once, children focus on the length of the line of eggs without simultaneously considering the amount of space between each egg. Piaget also suggested that children fail to think about reversibility. That is, they do not consider the fact that the operation that made the line of eggs longer could be reversed: The eggs could be repositioned more closely together, and the line would become shorter. Both of these tendencies make it difficult for the preoperational child to recognize that a longer line of eggs doesn’t necessarily mean more eggs.

But there is an even deeper reason why preoperational children do not fully grasp the notion of conservation: They do not fully grasp the fact that they have minds and that these minds contain mental representations of the world! As adults, we naturally distinguish between the subjective and the objective, between appearances and realities, between things in the mind and things in the world. We realize that things aren’t always as they seem: A wagon can be red but look gray at dusk, and a highway can be dry but look wet in the heat. We make a distinction between the way things are and the way we see them. Visual illusions delight us precisely because we know that they look like this but are really like that. Preoperational children don’t make this distinction. When something looks gray or wet, they assume it is gray or wet.

As children move from the preoperational to the concrete operational stage, they have a major epiphany that will stay with them for the rest of their lives: The way the world appears is not necessarily the way the world really is. They realize that their minds represent—

What is the essential feature of the formal operational stage?

437

Once children are at the concrete operational stage, they can readily solve physical problems involving egg-

Discovering Other Minds

As children develop, they discover their own minds, but they also discover the minds of others. Because preoperational children don’t fully grasp the fact that they have minds that mentally represent objects, they also don’t fully grasp the fact that other people have minds that may mentally represent the same objects in different ways. As such, preoperational children generally expect others to see the world as they do. When 3-

What does the false-

Perceptions and Beliefs. Just as 3-

Some researchers believe that the false-

438

Just as egocentrism affects children’s understandings of others’ minds, so does it affect their understanding of their own minds. Researchers showed young children an M&M’s box and then opened it, revealing that it contained pencils instead of candy. Then the researchers closed the box and asked, “When I first showed you the box all closed up like this, what did you think was inside?” Although most 5-

Do children understand emotions better than beliefs?

Desires and Emotions. Different people have different perceptions and beliefs. They also have different desires and emotions. Do children understand that these aspects of other people’s mental lives may also differ from their own? Surprisingly, even very young children who do not yet fully understand that others have different perceptions or beliefs do seem to understand that other people have different desires. For example, a 2-

In contrast, children take a much longer time to understand that other people may have emotional reactions unlike their own. When 5-

Theory of mind. Clearly, children have a whole lot to learn about how the mind works—

Which children have special difficulty acquiring a theory of mind?

439

Most of us eventually acquire a theory of mind, but two groups of people are somewhat slower to do so. Children with autism (a disorder we’ll cover in more depth in the Disorders chapter) typically have difficulty communicating with other people and making friends, and some psychologists have suggested that this is because they have trouble acquiring a theory of mind (Frith, 2003). Although children with autism are typically normal on most intellectual dimensions—

The second group of children who lag behind their peers in acquiring a theory of mind are deaf children whose parents do not know sign language. These children are slow to learn to communicate because they do not have ready access to any form of conventional language, and this restriction seems to slow the development of their understanding of other minds. Like children with autism, they display difficulties in understanding false beliefs even at 5 or 6 years of age (DeVilliers, 2005; Peterson & Siegal, 1999). Just as learning a spoken language seems to help hearing children acquire a theory of mind, so does learning a sign language help deaf children do the same (Pyers & Senghas, 2009).

The age at which children acquire a theory of mind appears to be influenced by a variety of other factors, such as the number of siblings the child has, the frequency with which the child engages in pretend play, whether the child has an imaginary companion, and the socioeconomic status of the child’s family. But of all the factors researchers have studied, language seems to be the most important (Astington & Baird, 2005). Children’s language skills are an excellent predictor of how well they perform on false-

Piaget Remixed. Cognitive development is an amazing and complex journey, and Piaget’s ideas about it were nothing short of groundbreaking. Few psychologists have had such a profound impact on the field. Many of these ideas have held up quite well, but in the last few decades, psychologists have discovered two general ways in which Piaget got it wrong. First, Piaget thought that children graduated from one stage to another in the same way that they graduated from kindergarten to first grade: a child is in kindergarten or first grade, he is never in both, and there is an exact moment of transition to which everyone with a clock or a calendar can point. Modern psychologists see development as more fluid and continuous: a less step-

440

What did Piaget get wrong?

The second thing about which Piaget was mistaken was the ages at which these transitions occur. By and large, they happen earlier than he realized (Gopnik, 2012). For example, Piaget suggested that infants had no sense of object permanence because they did not actively search for objects that were moved out of their sight. But when researchers use experimental procedures that allow infants to “show what they know,” even 4-

Discovering Our Cultures

How does culture affect cognitive development?

Piaget saw the child as a lone scientist who made observations, developed theories, and then revised those theories in light of new observations. And yet, most scientists don’t start from scratch. Rather, they receive training from more experienced scientists and they inherit the theories and methods of their disciplines. According to Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky, children do much the same thing. Vygotsky was born in 1896, the same year as Piaget, but unlike Piaget, he believed that cognitive development was largely the result of the child’s interaction with members of his or her own culture rather than his or her interaction with concrete objects. Vygotsky noted that cultural tools, such as language and counting systems, exert a strong influence on cognitive development (Vygotsky, 1978).

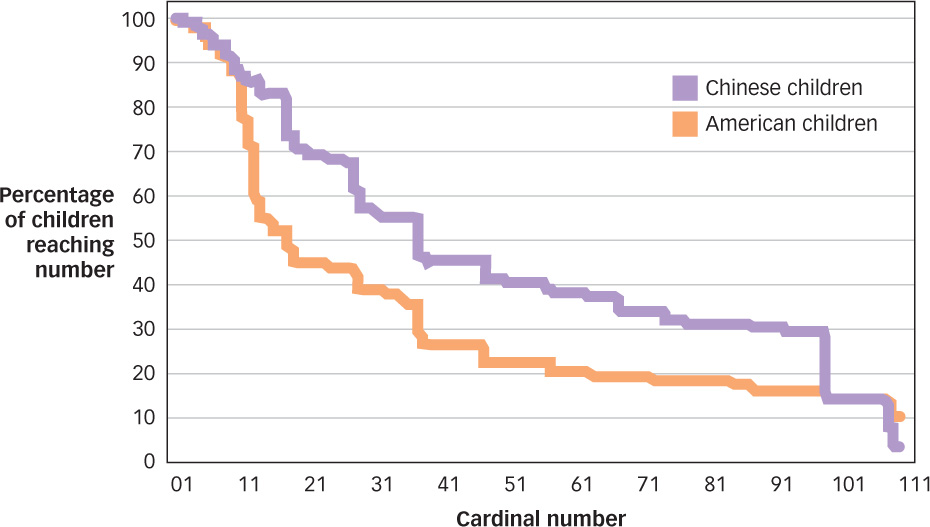

For example, in English, the numbers beyond 20 are named by a decade (twenty) that is followed by a digit (one) and their names follow a logical pattern (twenty-

Figure 11.5: Twelve or Two-

Figure 11.5: Twelve or Two-

Of course, if you’ve ever tried to train a pet snake, you already know that not all species are well prepared to learn from others. Human beings are the champions in this regard, because they have three skills that make them nature’s most exceptional students (Meltzoff et al., 2009; Striano & Reid, 2006).

441

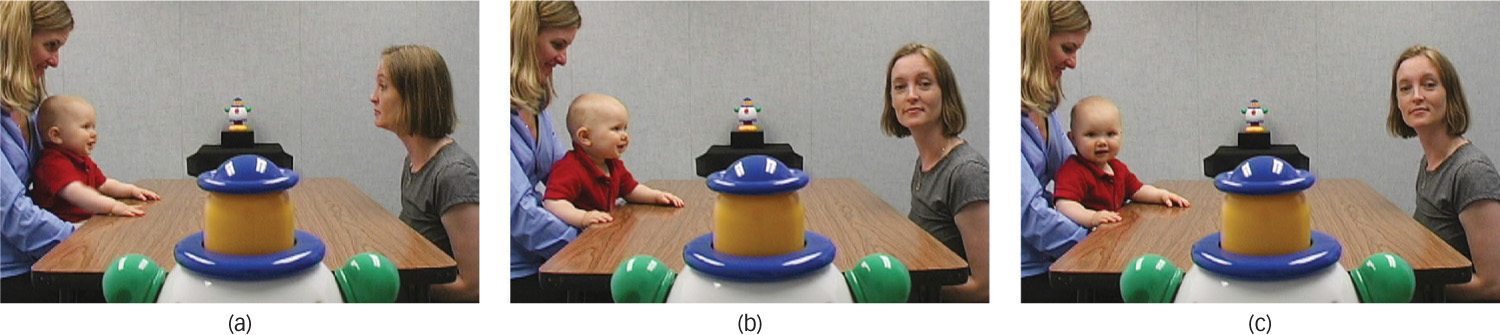

If an adult turns her head to the left, young infants (3 months) and older infants (9 months) will look to the left. But if the adult first closes her eyes and then looks to the left, the young infant will look to the left but the older infant will not (Brooks & Meltzoff, 2002). This suggests that older infants are not following the adult’s head movements, but rather, they are following her gaze: They are trying to see what they think she is seeing. If older infants can hear but not see an adult, they will use auditory cues to determine which way the adult must be looking and will then look in that direction (Rossano, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2012). The ability to focus on what another person is focused on is known as joint attention and it is a prerequisite for learning what others have to teach (see FIGURE 11.6).

If an adult turns her head to the left, young infants (3 months) and older infants (9 months) will look to the left. But if the adult first closes her eyes and then looks to the left, the young infant will look to the left but the older infant will not (Brooks & Meltzoff, 2002). This suggests that older infants are not following the adult’s head movements, but rather, they are following her gaze: They are trying to see what they think she is seeing. If older infants can hear but not see an adult, they will use auditory cues to determine which way the adult must be looking and will then look in that direction (Rossano, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2012). The ability to focus on what another person is focused on is known as joint attention and it is a prerequisite for learning what others have to teach (see FIGURE 11.6).

Figure 11.6: Joint Attention Joint attention allows children to learn from others. When a 12-

Figure 11.6: Joint Attention Joint attention allows children to learn from others. When a 12-month- old infant interacts with an adult (a) who then looks at an object (b), the infant will typically look at the same object (c)—but only when the adult’s eyes are open (Meltzo et al., 2009). A.N. MELTZOF, P.K. KUHL, T.J. SENJOWSKI, & J. MOVELLAN. “FOUNDATIONS FOR A NEW SCIENCE OF LEARNING” PUBLISHED IN SCIENCE, 2009, VOL. 325, JULY 17, PP. 284–288. Infants are natural mimics who often do what they see adults do (Jones, 2007). But very early on, infants begin to mimic adults’ intentions rather than their actions per se. When an 18-

Infants are natural mimics who often do what they see adults do (Jones, 2007). But very early on, infants begin to mimic adults’ intentions rather than their actions per se. When an 18-month- old sees an adult’s hand slip as the adult tries to pull the lid off a jar, the infant won’t copy the slip, but will instead perform the intended action by removing the lid (Meltzoff, 1995, 2007). The tendency to do what an adult does— or what an adult meant to do— is known as imitation. By the age of 3, children begin to copy adults so precisely that they will even copy parts of actions that they know to be pointless, a phenomenon called overimitation (Lyons, Young, & Keil, 2007; Simpson & Riggs, 2011).  An infant who approaches a new toy will often stop and look back at his or her mother, examining her face for cues about whether mom thinks the toy is or isn’t dangerous. The ability to use another person’s reactions as information about how we should think about the world is known as social referencing (Kim, Walden, & Knieps, 2010; Walden & Ogan, 1988). (You’ll learn a lot more about how adults continue to use this skill when we discuss informational influence in the Social Psychology chapter).

An infant who approaches a new toy will often stop and look back at his or her mother, examining her face for cues about whether mom thinks the toy is or isn’t dangerous. The ability to use another person’s reactions as information about how we should think about the world is known as social referencing (Kim, Walden, & Knieps, 2010; Walden & Ogan, 1988). (You’ll learn a lot more about how adults continue to use this skill when we discuss informational influence in the Social Psychology chapter).

Joint attention (“I see what you see”), imitation (“I do what you do”), and social referencing (“I think what you think”) are the three basic abilities that allow infants to learn from other members of their species.

442

THE REAL WORLD: Walk This Way

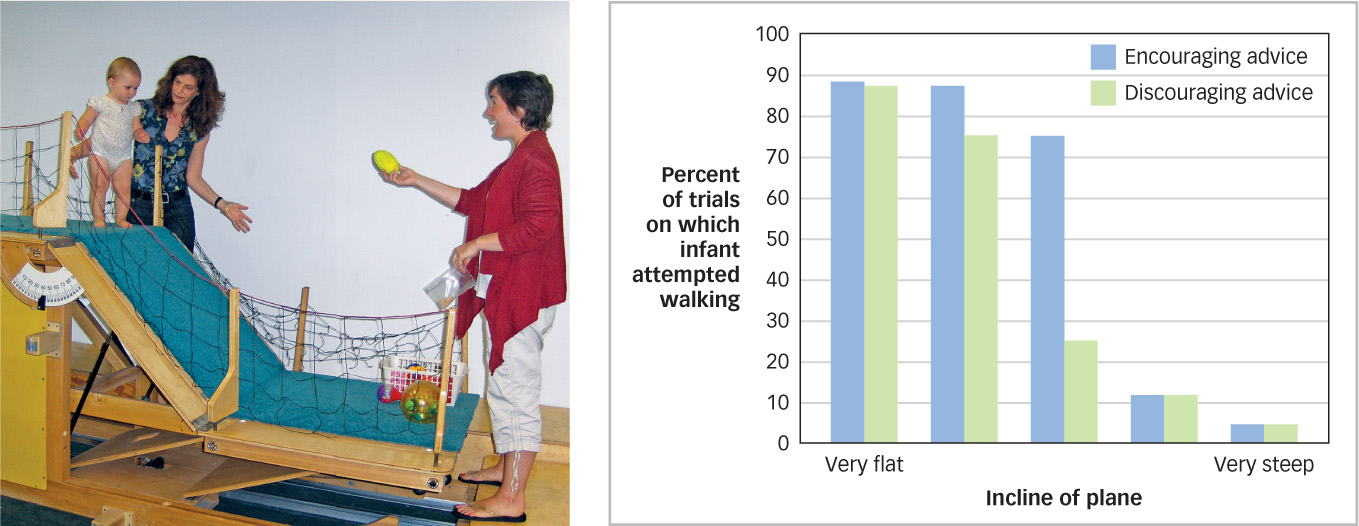

Parents often complain that their children won’t take their advice. But research shows that even 18-

Researchers (Tamis-

So what did the infants do? Did they trust their mothers or did they trust their eyes? As you can see in the figure below, when the inclined plane was clearly safe or clearly risky, infants ignored their mothers. They typically trotted down the flat plane even when mom advised against it and refused to try the risky plane even when mom said it was okay. But when the plane was somewhere between safe and risky, the infants tended to follow mom’s advice.

These data show that infants use social information in a very sophisticated way. When their senses provide unambiguous information about the world, they ignore what people tell them. But when their senses leave them unsure about what to do, they readily accept parental advice. It appears that from the moment children start to walk, they know when to listen to their parents and when to shake their heads, roll their eyes, and do what they darn well please.

Social Development

Unlike baby turtles, baby humans cannot survive without their caregivers. But what exactly do caregivers provide? Some obvious answers are warmth, safety, and food, and those obvious answers are right. But caregivers also provide something that is far less obvious but every bit as essential to an infant’s development.

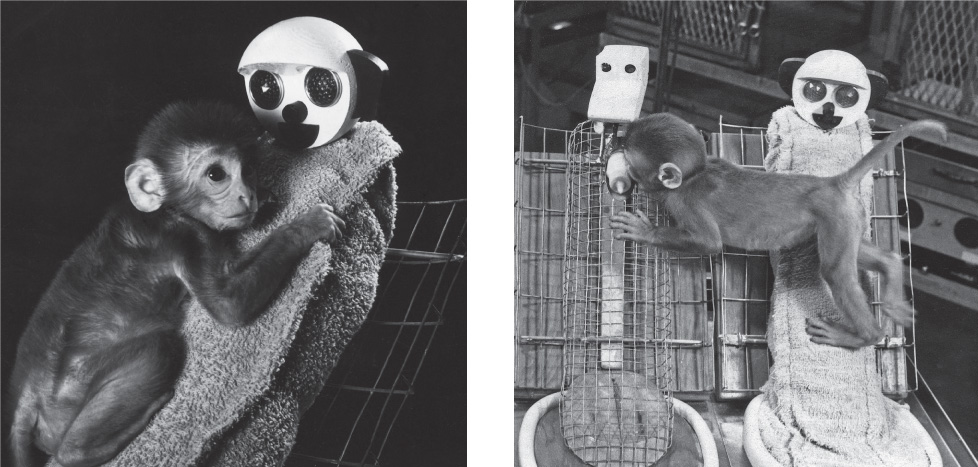

During World War II, psychologists studied infants who were living in orphanages while awaiting adoption. Although these children were warm, safe, and well fed, many were developmentally impaired, both physically and psychologically, and nearly 40% died before they could be adopted (Spitz, 1949). A few years later, psychologist Harry Harlow (1958; Harlow & Harlow, 1965) discovered that infant rhesus monkeys that were warm, safe, and well fed, but were not allowed any social contact for the first 6 months of their lives, developed a variety of behavioral abnormalities. They compulsively rocked back and forth while biting themselves, and if they were introduced to other monkeys, they avoided them entirely. These socially isolated monkeys turned out to be incapable of communicating with or learning from others of their kind, and when the females matured and became mothers, they ignored, rejected, and sometimes even attacked their own infants. Harlow also discovered that when socially isolated monkeys were put in a cage with two “artificial mothers”—one that was made of wire and dispensed food and one that was made of cloth and dispensed no food—

443

SCIENCE SOURCE

Becoming Attached

How does an infant identify the primary caregiver?

When Konrad Lorenz was a child he became the proud owner of a duck, and he quickly noticed something very interesting. Several decades later, the thing he had noticed helped him win the Nobel Prize. As he explained in his acceptance speech, “From a neighbor, I got a one-

©PETER BURIAN/CORBIS

Psychiatrist John Bowlby was fascinated by Lorenz’s work, as well as by Harlow’s studies of rhesus monkeys reared in isolation and the work on children reared in orphanages, and he sought to understand how human infants form attachments to their caregivers (Bowlby, 1969, 1973, 1980). Bowlby began by noting that from the moment they are born, ducks waddle after their mothers and monkeys cling to their mothers’ furry chests because the newborns of both species must stay close to their caregivers to survive. Human infants, he suggested, have a similar need, but they are much less physically developed than ducks or monkeys and therefore can neither waddle nor cling. What they can do is smile and cry. Because they do not have webbed feet or furry hands that allow them to stay close to their caregivers, they use what they do have to keep their caregivers close to them. When an infant cries, gurgles, coos, makes eye contact, or smiles, most adults reflexively move toward the infant, and Bowlby suggested that this is why infants have been designed to emit these signals.

According to Bowlby, infants initially send these signals to anyone within visual or auditory range. For the first 6 months or so, they keep a “mental tally” of who responds most often and most promptly to their signals, and soon they begin to target the best and fastest responder, also known as the primary caregiver. This person quickly becomes the emotional center of the infant’s universe. Infants feel secure in the primary caregiver’s presence and will happily crawl around, exploring their environments with their eyes, ears, fingers, and mouths. But if their primary caregiver gets too far away, infants begin to feel insecure, and they take action to decrease the distance between themselves and their primary caregiver, perhaps by crawling toward their caregiver or perhaps by crying until their caregiver moves toward them. Bowlby believed that all of this happens because evolution has equipped human infants with a social reflex that is every bit as basic as the physical reflexes that cause them to suck and to grasp. Human infants, Bowlby suggested, are predisposed to form an attachment—that is, an emotional bond—with a primary caregiver.

444

How is attachment assessed?

Infants who are deprived of the opportunity to become attached experience a variety of negative consequences (Gillespie & Nemeroff, 2007; O’Connor & Rutter, 2000; Rutter, O’Connor, & the English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team, 2004). But even when attachment does happen, it can happen more or less successfully (Ainsworth et al., 1978). Psychologist Mary Ainsworth developed a way to measure this: Strange Situation is a behavioral test used to determine a child’s attachment style. The test involves bringing a child and his or her primary caregiver (usually the child’s mother) to a laboratory room and then staging a series of episodes, including ones in which the primary caregiver briefly leaves the room and then returns, while psychologists monitor the infant’s reaction. Research shows that those reactions tend to fall into one of four patterns known as attachment styles.

About 60% of American infants have a secure attachment style. When the caregiver leaves, the infant may or may not be distressed. When she returns, non-

About 60% of American infants have a secure attachment style. When the caregiver leaves, the infant may or may not be distressed. When she returns, non-distressed infants will acknowledge her with a glance or greeting, and distressed infants will go to her and are calmed by her presence.  About 20% of American infants have an avoidant attachment style. When the caregiver leaves, the infant will not be distressed, and when she returns the infant will not acknowledge her.

About 20% of American infants have an avoidant attachment style. When the caregiver leaves, the infant will not be distressed, and when she returns the infant will not acknowledge her. About 15% of American infants have an ambivalent attachment style. When the caregiver leaves the infant will be distressed, and when she returns the infant will rebuff her, refusing any attempt at calming while arching his or her back and squirming to get away.

About 15% of American infants have an ambivalent attachment style. When the caregiver leaves the infant will be distressed, and when she returns the infant will rebuff her, refusing any attempt at calming while arching his or her back and squirming to get away. About 5% or fewer American infants have a disorganized attachment style. These infants show no consistent pattern of response to their caregiver’s leaving and returning.

About 5% or fewer American infants have a disorganized attachment style. These infants show no consistent pattern of response to their caregiver’s leaving and returning.

Research has shown that a child’s behavior in the Strange Situation in the laboratory correlates fairly well with his or her behavior at home (Solomon & George, 1999; see FIGURE 11.7). Nonetheless, it is not unusual for a child’s attachment style to change over time (Lamb, Sternberg, & Prodromidis, 1992). And although some aspects of attachment styles appear to be stable across cultures—

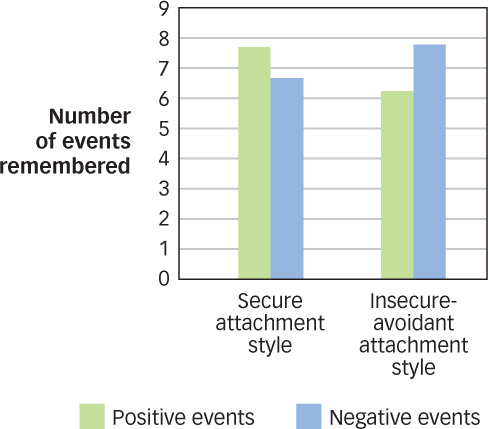

Figure 11.7: Attachment Style and Memory We often remember best those events that fit with our view of the world. Researchers assessed 1-

Figure 11.7: Attachment Style and Memory We often remember best those events that fit with our view of the world. Researchers assessed 1-445

Where Do Attachment Styles Come From?

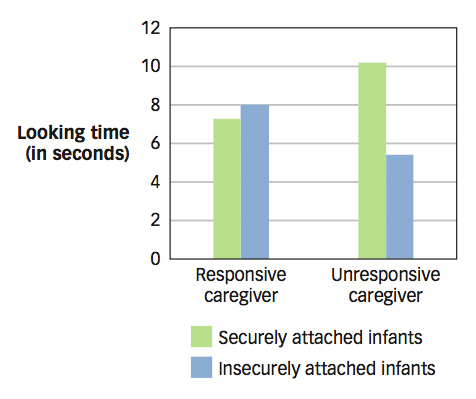

Figure 11.8: Working Models Do infants really have internal working models? It appears they do. Psychologists know that infants stare longer when they see something they don’t expect, and securely attached infants stare longer at a cartoon of a mother ignoring rather than comforting her child, whereas insecurely attached infants do just the opposite (Johnson, Dweck, & Chen, 2007).

Figure 11.8: Working Models Do infants really have internal working models? It appears they do. Psychologists know that infants stare longer when they see something they don’t expect, and securely attached infants stare longer at a cartoon of a mother ignoring rather than comforting her child, whereas insecurely attached infants do just the opposite (Johnson, Dweck, & Chen, 2007).

A child’s attachment style is determined in part by the child’s biology. Different children are born with different temperaments, or characteristic patterns of emotional reactivity (Thomas & Chess, 1977). Whether measured by parents’ reports or by physiological indices such as heart rate or cerebral blood flow, very young children vary in their tendency toward fearfulness, irritability, activity, positive affect, and other emotional traits (Rothbart & Bates, 1998). These differences are unusually stable over time. For example, infants who react fearfully to novel stimuli—

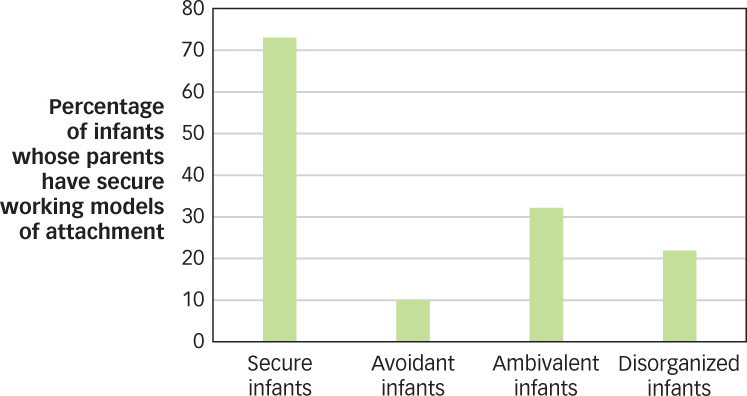

Figure 11.9: Parents’ Attachment Styles Attachment is an interaction between two people, and both of them—

Figure 11.9: Parents’ Attachment Styles Attachment is an interaction between two people, and both of them—The infant’s biologically based temperament plays a role in determining his or her attachment style, but for the most part, attachment style is determined by the infant’s social interactions with his or her caregiver. Studies have shown that mothers of securely attached infants tend to be especially sensitive to signs of their child’s emotional state, especially good at detecting their infant’s “request” for reassurance, and especially responsive to that request (Ainsworth et al., 1978; De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997). Mothers of infants with an ambivalent attachment style tend to respond inconsistently, only sometimes attending to their infants when they show signs of distress. Mothers of infants with an avoidant attachment style are typically indifferent to their child’s need for reassurance and may even reject their attempts at physical closeness (Isabelle, 1993). As a result of all this, infants develop an internal working model of relationships, which is a set of beliefs about the self, the primary caregiver, and the relationship between them (Bretherton & Munholland, 1999). Infants with different attachment styles appear to have different working models of relationships (see FIGURE 11.8). Specifically, infants with a secure attachment style act as though they are certain that their primary caregiver will respond when they feel insecure; infants with an avoidant attachment style act as though they are certain that their primary caregiver will not respond; and infants with an ambivalent attachment style act as though they are uncertain about whether their primary caregiver will respond. Infants with a disorganized attachment style seem to be confused about their caregivers, which has led some psychologists to speculate that this style primarily characterizes children who have been abused (Carolson, 1998; Cicchetti & Toth, 1998).

How do caregivers influence an infant’s attachment style?

If the caregiver’s responsiveness determines (in large part) the child’s working model, and if the child’s working model determines (in large part) the child’s attachment style, then what determines the caregiver’s responsiveness (see FIGURE 11.9)? Differences in how caregivers respond are probably due (in large part) to differences in their ability to read their infant’s emotional states. Caregivers who are highly sensitive to these signs are almost twice as likely to have a securely attached child as are mothers who are less sensitive (van Ijzendoorn & Sagi, 1999). Mothers who think of their infants as unique individuals with emotional lives and not just as creatures with urgent physical needs are more likely to have infants who are securely attached (Meins, 2003; Meins et al., 2001). Although such data are merely correlational, there is reason to suspect that a mother’s sensitivity and responsiveness are a cause of the infant’s attachment style. For instance, researchers studied a group of young mothers whose infants were particularly irritable or difficult. When the infants were about 6 months old, half the mothers participated in a training program designed to sensitize them to their infants’ emotional signals and to encourage them to be more responsive. The results showed that when the children were 18 months, 24 months, and 3 years old, those whose mothers had received the training were considerably more likely to have a secure attachment style than were those whose mothers did not receive the training (van den Boom, 1994, 1995).

446

Do Attachment Styles Matter?

Does an infant’s attachment style have any influence on his or her subsequent development? Children who were securely attached as infants do better than children who were not securely attached on a wide variety of measures, from their psychological well-

For example, in one study that tracked people from infancy to adulthood, researchers found that 1-

Moral Development

From the moment of birth, human beings can make one distinction quickly and well, and that’s the distinction between pleasure and pain. Before their bottoms hit their very first diapers, infants can tell when something feels good or bad, and can demonstrate to anyone within earshot that they strongly prefer the former. Over the next few years, they begin to notice that their pleasures (“Throwing food is fun”) are often someone else’s pains (“Throwing food makes Mom mad”), which is a bit of a problem because infants need these other people to survive. So they start to learn how to balance their needs and the needs of those around them, and they do this in part by developing a distinction between right and wrong.

447

Knowing What’s Right

According to Piaget, what three shifts characterize moral development?

How do children think about right and wrong? Piaget had something to say about this too. He spent time playing games with children and quizzing them about how they came to know the rules of these games and what they thought should happen to children who broke those rules. By listening carefully to what children said, Piaget concluded that the child’s moral thinking develops in three important ways (Piaget, 1932/1965).

First, Piaget noticed that children’s moral thinking tends to shift from realism to relativism. Very young children regard moral rules as real, inviolable truths about the world. For the young child, right and wrong are like day and night: They exist in the world and do not depend on what people think or say. That’s why young children generally don’t think that a bad action (such as hitting someone) can ever be good, even if everyone agreed to allow it. As they mature, children begin to realize that some moral rules (e.g., wives should obey their husbands) are inventions and not discoveries and that people can therefore agree to adopt them, change them, or abandon them entirely.

First, Piaget noticed that children’s moral thinking tends to shift from realism to relativism. Very young children regard moral rules as real, inviolable truths about the world. For the young child, right and wrong are like day and night: They exist in the world and do not depend on what people think or say. That’s why young children generally don’t think that a bad action (such as hitting someone) can ever be good, even if everyone agreed to allow it. As they mature, children begin to realize that some moral rules (e.g., wives should obey their husbands) are inventions and not discoveries and that people can therefore agree to adopt them, change them, or abandon them entirely. According to Piaget, young children do not realize that moral rules can vary across persons and cultures. For instance, most Americans think it is immoral to eat a dog, but most Vietnamese disagree.HOANG DINH NAM/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

According to Piaget, young children do not realize that moral rules can vary across persons and cultures. For instance, most Americans think it is immoral to eat a dog, but most Vietnamese disagree.HOANG DINH NAM/AFP/GETTY IMAGES Second, Piaget noticed that children’s moral thinking tends to shift from prescriptions to principles. Young children think of moral rules as guidelines for specific actions in specific situations (“Each child can play with the iPad for 5 minutes and must then pass it to the child sitting to their left”). As they mature, children come to see that rules are expressions of more general principles, such as fairness and equity, which means that specific rules can be abandoned or modified when they fail to uphold the general principle (“If Jason missed his turn with the iPad, then he should get two turns now”).

Second, Piaget noticed that children’s moral thinking tends to shift from prescriptions to principles. Young children think of moral rules as guidelines for specific actions in specific situations (“Each child can play with the iPad for 5 minutes and must then pass it to the child sitting to their left”). As they mature, children come to see that rules are expressions of more general principles, such as fairness and equity, which means that specific rules can be abandoned or modified when they fail to uphold the general principle (“If Jason missed his turn with the iPad, then he should get two turns now”). Third and finally, Piaget noticed that children’s moral thinking tends to shift from outcomes to intentions. For the young child, an unintentional action that causes great harm (“Josh accidentally broke Dad’s iPad”) seems “more wrong” than an intentional action that causes slight harm (“Josh got mad and broke Dad’s pencil”) because young children tend to judge the morality of an action by its outcome rather than by the actor’s intentions. As they mature, children begin to see that the morality of an action is critically dependent on the actor’s state of mind.

Third and finally, Piaget noticed that children’s moral thinking tends to shift from outcomes to intentions. For the young child, an unintentional action that causes great harm (“Josh accidentally broke Dad’s iPad”) seems “more wrong” than an intentional action that causes slight harm (“Josh got mad and broke Dad’s pencil”) because young children tend to judge the morality of an action by its outcome rather than by the actor’s intentions. As they mature, children begin to see that the morality of an action is critically dependent on the actor’s state of mind.

Piaget’s observations about the development of moral thinking have generally held up quite well, although he once again seemed to overestimate the ages at which some of these transitions take place. For example, research shows that children as young as 3 years old do sometimes consider people’s intentions when judging the morality of their actions (Yuill & Perner, 1988). Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg used Piaget’s insights to produce a detailed theory of the development of moral reasoning (Kohlberg, 1963, 1986). According to Kohlberg, moral reasoning proceeds through three basic stages. Kohlberg (1958) based his theory on people’s responses to a series of dilemmas such as this one:

448

What are Kohlberg’s three stages of moral development?

A woman was near death from a special kind of cancer. There was one drug that the doctors thought might save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging ten times what the drug cost him to make. He paid $200 for the radium and charged $2,000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick woman’s husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about $1,000, which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said: “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” So Heinz got desperate and broke into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. Should the husband have done that?

On the basis of their responses, Kohlberg concluded that most children are at the preconventional stage, which is a stage of moral development in which the morality of an action is primarily determined by its consequences for the actor. Immoral actions are simply those for which one is punished, and the appropriate resolution to any moral dilemma is to choose the behavior with the least likelihood of punishment. For example, children at this stage often base their moral judgment of Heinz on the relative costs of one decision (“It would be bad if he got blamed for his wife’s death”) and another (“It would be bad if he went to jail for stealing”).

Kohlberg argued that children are preconventional, but somewhere around adolescence they move to the conventional stage, which is a stage of moral development in which the morality of an action is primarily determined by the extent to which it conforms to social rules. People at this stage believe that everyone should uphold the generally accepted norms of their cultures, obey the laws of society, and fulfill their civic duties and familial obligations. They argue that Heinz must weigh the dishonor he will bring upon himself and his family by stealing (i.e., breaking a law) against the guilt he will feel if he allows his wife to die (i.e., failing to fulfill a duty). People at this stage are concerned not just about spankings and prison sentences but also about the approval of others. Immoral actions are those for which one is condemned.

What was Kohlberg right about and wrong about?

Finally, Kohlberg believed that in adulthood, some adults (but not all) move to the postconventional stage, which is a stage of moral development in which the morality of an action is determined by a set of general principles that reflect core values, such as the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. When a behavior violates these principles, it is immoral, and if a law requires these principles to be violated, then it should be disobeyed. For a person who has reached the postconventional stage, a woman’s life is always more important than a shopkeeper’s profits and so stealing the drug is not only a moral behavior, it is a moral obligation.

Research supports Kohlberg’s general claim that moral reasoning shifts from an emphasis on punishment to an emphasis on social rules and finally to an emphasis on ethical principles (Walker, 1988). But research also suggests that these stages are not quite as discrete as Kohlberg thought. For instance, a single person may use preconventional, conventional, and postconventional thinking in different circumstances, which suggests that the developing person does not “reach a stage” so much as he “acquires a skill” that he may or may not use on a particular occasion.

The use of the male pronoun here is intentional. Because Kohlberg developed his theory by studying a sample of American boys, some critics have suggested that it does not describe the development of moral thinking in girls (Gilligan, 1982) or in non-

449

Feeling What’s Right

Research on moral reasoning suggests that people are like judges in a court of law, using rational analysis—

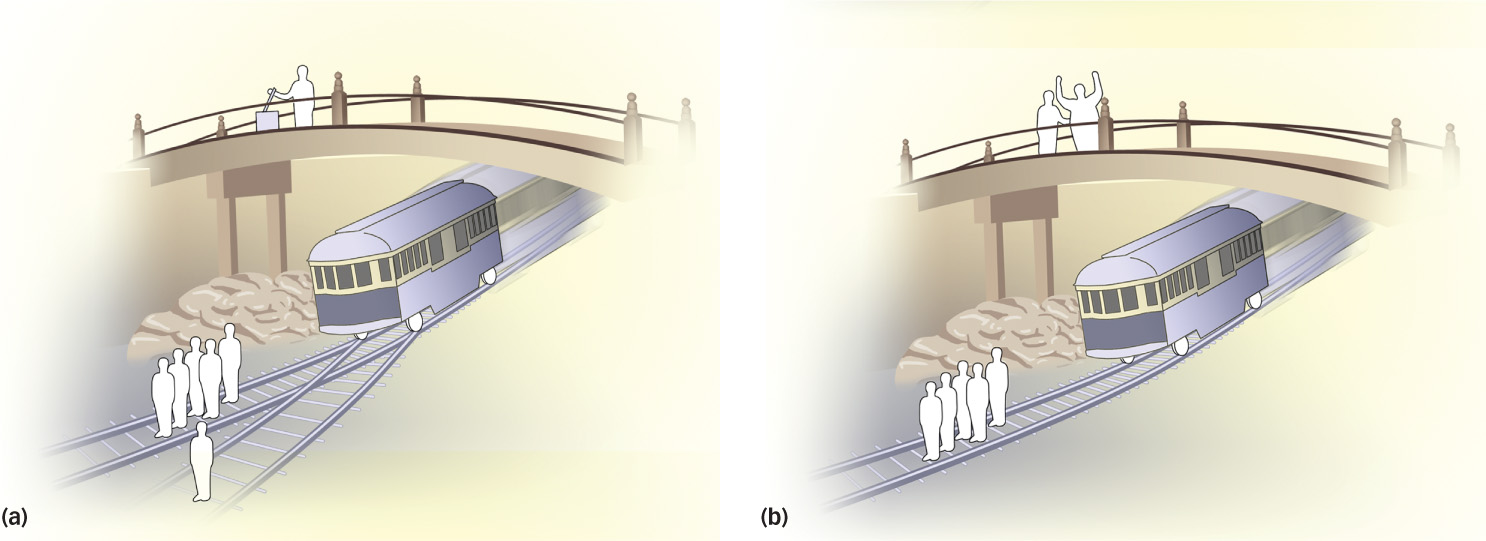

You are standing on a bridge. Below you can see a runaway trolley hurtling down the track toward five people who will be killed if it remains on its present course. You are sure that you can save these people by flipping a lever that will switch the trolley onto a different track, where it will kill just one person instead of five. Is it morally permissible to divert the trolley and prevent five deaths at the cost of one?

Now consider a slightly different version of this problem:

You and a large man are standing on a bridge. Below you can see a runaway trolley hurtling down the track toward five people who will be killed if it remains on its present course. You are sure that you can save these people by pushing the large man onto the track, where his body will be caught up in the trolley’s wheels and stop it before it kills the five people. Is it morally permissible to push the large man and prevent five deaths at the cost of one?

These scenarios are illustrated in FIGURE 11.10. If you are like most people, you concluded that is morally permissible to pull a switch but not to push a man (Greene et al., 2001). In both cases you had to decide whether to sacrifice one human life in order to save five, and in one case you said yes and in another you said no. How can moral reasoning yield such inconsistent conclusions? It can’t, and the odds are that you didn’t reach these conclusions by moral reasoning at all. Rather, you simply had a strong negative emotional reaction to the thought of pushing another human being into the path of an oncoming trolley and watching him get sliced and diced, and that reaction instantly led you to conclude that pushing him was wrong. Sure, you may have come up with a few good arguments to support this conclusion (“What if he turned around and bit me?” or “I’d hate to get spleen on my new shoes”), but those arguments probably followed rather than preceded your conclusion (Greene, 2013).

Figure 11.10: The Trolley Problem Why does it seem permissible to trade one life for five lives by pulling a switch but not by pushing a man from a bridge? Research suggests that the scenario shown in (b) elicits a more negative emotional response than does the scenario shown in (a), and this emotional response may be the basis for our moral intuitions.

Figure 11.10: The Trolley Problem Why does it seem permissible to trade one life for five lives by pulling a switch but not by pushing a man from a bridge? Research suggests that the scenario shown in (b) elicits a more negative emotional response than does the scenario shown in (a), and this emotional response may be the basis for our moral intuitions.

Do moral judgments come before or after emotional reactions?

450

The way people respond to cases such as these has convinced some psychologists that moral judgments are the consequences—

What happens when we see others suffer?

Some research supports the moral intuitionist perspective. For example, in one study, people who had brain damage that prevented them from experiencing normal emotions treated the two situations shown in Figure 11.10 identically, choosing in both cases to sacrifice one life to save five (Koenigs et al., 2007). In another study (Wheatley & Haidt, 2005), participants were hypnotized and told that whenever they heard the word take, they would experience “a brief pang of disgust…a sickening feeling in your stomach.” After they came out of the hypnotic state, the participants were asked to rate the morality of several actions. Sometimes the description of the action contained the word take (“How immoral is it for a police officer to take a bribe”) and sometimes it did not (“How immoral is it for a police officer to accept a bribe?”). Participants rated the action as less moral when it contained the word take, suggesting that their negative feelings were causing—

All of this suggests that we consider it immoral to push someone onto the tracks simply because the idea of watching someone suffer makes us feel bad (Greene et al., 2001). In fact, research has shown that watching someone suffer activates the very same brain regions that are activated when we suffer ourselves (Carr et al., 2003; see the discussion of mirror neurons in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter). In one study, women received a shock or watched their romantic partners receive a shock on different parts of their bodies. The regions of the women’s brains that processed information about the location of the shock were activated only when the women experienced the shock themselves, but the regions that processed emotional information were activated whether the women received the shock or observed it (Singer et al., 2004). Similarly, the emotion-

451

This may also explain why our aversion to watching others suffer begins so early in childhood (Warneken & Tomasello, 2009). When adults pretend to hit their thumbs with a hammer, even very young children seem alarmed and will attempt to comfort them (Zahn-

Infants have a limited range of vision, but they can see and remember objects that appear within it. They learn to control their bodies from the top down and from the center out.

Infants have a limited range of vision, but they can see and remember objects that appear within it. They learn to control their bodies from the top down and from the center out. Infants slowly develop theories about how the world works. Piaget believed that these theories developed through four stages, in which children learn basic facts about the world, such as the fact that objects continue to exist even when they are out of sight, and the fact that objects have enduring properties that are not changed by superficial transformations. Children also learn that their minds represent objects; hence objects may not be as they appear, and others may not see them as the child does.

Infants slowly develop theories about how the world works. Piaget believed that these theories developed through four stages, in which children learn basic facts about the world, such as the fact that objects continue to exist even when they are out of sight, and the fact that objects have enduring properties that are not changed by superficial transformations. Children also learn that their minds represent objects; hence objects may not be as they appear, and others may not see them as the child does. Cognitive development also comes about through social interactions in which children are given tools for understanding that have been developed over millennia by members of their cultures.

Cognitive development also comes about through social interactions in which children are given tools for understanding that have been developed over millennia by members of their cultures. At a very early age, human beings develop strong emotional ties to their primary caregivers. The quality of these ties is determined both by the caregiver’s behavior and the child’s temperament.

At a very early age, human beings develop strong emotional ties to their primary caregivers. The quality of these ties is determined both by the caregiver’s behavior and the child’s temperament. People get along with each other by learning and obeying moral principles.

People get along with each other by learning and obeying moral principles. Children’s reasoning about right and wrong is initially based on an action’s consequences, but as they mature, children begin to consider the actor’s intentions as well as the extent to which the action obeys abstract moral principles.

Children’s reasoning about right and wrong is initially based on an action’s consequences, but as they mature, children begin to consider the actor’s intentions as well as the extent to which the action obeys abstract moral principles. Moral judgments may be caused by our emotional reactions to the suffering of others.

Moral judgments may be caused by our emotional reactions to the suffering of others.