12.1 Personality: What It Is and How It Is Measured

If someone said, “You have no personality,” how would you feel? Like a cookie-

Describing and Explaining Personality

As the first biologists earnestly attempted to classify all plants and animals (whether lichens or ants or fossilized lions), personality psychologists began by labeling and describing different personalities. And just as biology came of age with Darwin’s theory of evolution, which explained how differences among species arose, the maturing study of personality also has developed explanations of the basis for psychological differences among people.

What does it mean to say that personality is in the eye of the beholder?

Most personality psychologists focus on specific, psychologically meaningful individual differences, characteristics such as honesty, anxiousness, or moodiness. Still, personality is often in the eye of the beholder. When one person describes another as “a conceited jerk,” for example, you may wonder whether you have just learned more about the describer or the person being described. Interestingly, studies that ask acquaintances to describe each other find a high degree of similarity among any one individual’s descriptions of many different people (“Jason thinks that Carlos is considerate, Renata is kind, and Jean Paul is nice to others”). In contrast, resemblance is quite low when many people describe one person (“Carlos thinks Jason is smart, Renata thinks he is competitive, and Jean Paul thinks he has a good sense of humor”; Dornbusch et al., 1965).

What leads Lady Gaga to all of her entertaining extremes? In general, explanations of personality differences are concerned with (1) prior events that can shape an individual’s personality or (2) anticipated events that might motivate the person to reveal particular personality characteristics. In a biological prior event, Stefani Germanotta received genes from her parents that may have led her to develop into the sort of person who loves putting on a display (not to mention putting on raw meat) and stirring up controversy. Researchers interested in events that happen prior to our behavior study our genes, brains, and other aspects of our biological makeup, and also delve into our subconscious and into our circumstances and interpersonal surroundings. The consideration of anticipated events emphasizes the person’s own, subjective perspective and often seems intimate and personal in its reflection of the person’s inner life (hopes, fears, and aspirations).

473

Of course, our understanding of how the baby named Stefani Germanotta grew into the adult Lady Gaga (or the life of any woman or man) also depends on insights into the interaction between the prior and anticipated events: We need to know how her history may have shaped her motivations.

Measuring Personality

Of all the things psychologists have set out to measure, personality may be one of the toughest. How do you capture the uniqueness of a person? What aspects of people’s personalities are important to know about, and how should we quantify them? The general personality measures can be classified broadly into personality inventories and projective techniques.

Personality Inventories

To learn about an individual’s personality, you could follow the person around and, clipboard in hand, record every single thing the person does, says, thinks, and feels (including how long this goes on before the person calls the police). Some observations might involve your own impressions (Day 5: seems to be getting irritable); others would involve objectively observable events that anyone could verify (Day 7: grabbed my pencil and broke it in half, then bit my hand).

| Here are a number of personality traits that may or may not apply to you. Please write a number next to each statement to indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with that statement. You should rate the extent to which the pair of traits applies to you, even if one characteristic applies more strongly than the other. |

| 1 = Disagree strongly 2 = Disagree moderately 3 = Disagree a little 4 = Neither agree nor disagree 5 = Agree a little 6 = Agree moderately 7 = Agree strongly |

|

I see myself as: 1. _____ Extraverted, enthusiastic 2. _____ Critical, quarrelsome 3. _____ Dependable, self- 4. _____ Anxious, easily upset 5. _____ Open to new experiences, complex 6. _____ Reserved, quiet 7. _____ Sympathetic, warm 8. _____ Disorganized, careless 9. _____ Calm, emotionally stable 10. _____ Conventional, uncreative |

| TIPI scale scoring (R = reverse- Source: Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, 2003. |

Psychologists have figured out ways to obtain objective data on personality without driving their subjects to violence. The most popular technique is self-report, a method in which people provide subjective information about their own thoughts, feelings, or behaviors, typically via questionnaire or interview. In most self-

How is a self-

474

What are some limitations of personality inventories?

One of the most commonly used personality tests is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), a well-

Personality inventories such as the MMPI–2–RF are easy to administer: All that is needed is the test and a pencil (or a computer-

Projective Techniques

Figure 12.1: Sample Rorschach Inkblot Test takers are shown a card such as this sample and asked, “What might this be?” What they perceive, where they see it, and why it looks that way are assumed to reflect unconscious aspects of their personality.

Figure 12.1: Sample Rorschach Inkblot Test takers are shown a card such as this sample and asked, “What might this be?” What they perceive, where they see it, and why it looks that way are assumed to reflect unconscious aspects of their personality.

A second, somewhat controversial, class of tools for evaluating personality designed to circumvent the limitations of self-

475

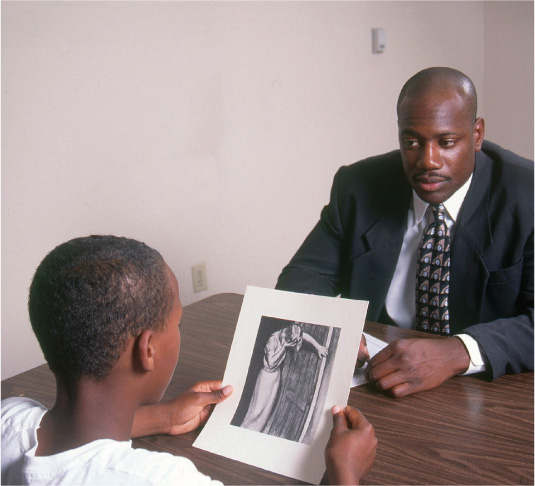

Figure 12.2: Sample TAT Card Test takers are shown cards with ambiguous scenes such as this sample and are asked to tell a story about what is happening in the picture. The main themes of the story, the thoughts and feelings of the characters, and how the story develops and resolves are considered useful indices of unconscious aspects of an individual’s personality (Murray, 1943).

Figure 12.2: Sample TAT Card Test takers are shown cards with ambiguous scenes such as this sample and are asked to tell a story about what is happening in the picture. The main themes of the story, the thoughts and feelings of the characters, and how the story develops and resolves are considered useful indices of unconscious aspects of an individual’s personality (Murray, 1943).

The Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) is a projective technique in which respondents’ underlying motives, concerns, and the way they see the social world are believed to be revealed through analysis of the stories they make up about ambiguous pictures of people. To get a sense of the test, look at FIGURE 12.2. The test administrator shows the respondent the card and asks him or her to tell a story about the picture, asking questions such as: Who are those people? What is happening? What led them to this moment? What will happen next? Different people tell very different stories about the image. In creating the stories, the respondent is thought to identify with the main characters and to project his or her view of others and the world onto the other details in the drawing. Thus, any details that are not obviously drawn from the picture are believed to be projected onto the story from the respondent’s own desires and internal conflicts.

What might limit the validity of the information obtained from projective tests?

Many of the TAT drawings tend to elicit a consistent set of themes, such as successes and failures, competition and jealousy, conflict with parents and siblings, feelings about intimate relationships, aggression, and sexuality. For instance, one card that shows an older man standing over a child lying in bed tends to elicit themes regarding relationships that respondents have with an older man in their life, such as a relationship with a father, teacher, boss, or therapist. The interviewer might be interested in learning whether respondents see the person lying down as a male or female, and whether they report that the man standing is trying to help or harm the person lying down. Consider a story proposed by a young man in response to this card: “The boy lying down had a hard day at school. He worked so hard studying for his exam that when he came home after taking the test he fell asleep with his clothes on. No matter how hard the boy tries, he can never make his father happy. The father is sick and tired of the son not doing well in school and so he is going to kill him. He suffocates the boy and the boy dies.” The test administrator might interpret this response as indicating that the respondent perceives that his father has high expectations that are not being met, and perhaps that the father is disappointed and angry with the young man.

The value of projective tests is debated by psychologists. Although they continue to be widely used by practicing clinicians, critics argue that tests such as the Rorschach and the TAT are open to the biases of the examiner. A TAT story like the one above may seem revealing; however, the examiner must always add an interpretation (Was this about the respondent’s actual father, about his own concerns about his academic failures, or about trying to be funny or provocative?), and that interpretation could well be the scorer’s own projection into the mind of the test taker. Thus, despite the rich picture of a personality and the insights into an individual’s motives that these tests offer, projective tests should be understood primarily as a way in which a psychologist can get to know someone personally and intuitively (McClelland et al., 1953). When measured by rigorous scientific criteria, projective tests such as the TAT and the Rorschach have not been found to be reliable or valid in predicting behavior (Lilienfeld, Lynn, & Lohr, 2003).

Newer personality measurement methods are moving beyond both self-

476

In psychology, personality refers to a person’s characteristic style of behaving, thinking, and feeling.

In psychology, personality refers to a person’s characteristic style of behaving, thinking, and feeling. Personality psychologists attempt to find the best ways to describe personality, to explain how personalities come about, and to measure personality.

Personality psychologists attempt to find the best ways to describe personality, to explain how personalities come about, and to measure personality. Two general classes of personality tests are personality inventories, such as the MMPI–2–RF, and projective techniques, such as the Rorschach Inkblot Test and the TAT. Newer high-

Two general classes of personality tests are personality inventories, such as the MMPI–2–RF, and projective techniques, such as the Rorschach Inkblot Test and the TAT. Newer high-tech methods are proving to be even more effective.