12.2 The Trait Approach: Identifying Patterns of Behavior

Imagine writing a story about the people you know. To capture their special qualities, you might describe their traits: Keesha is friendly, aggressive, and domineering; Seth is flaky, humorous, and superficial. With a dictionary and a free afternoon, you might even be able to describe William as perspicacious, flagitious, and callipygian. The trait approach to personality uses such trait terms to characterize differences among individuals. In attempting to create manageable and meaningful sets of descriptors, trait theorists face two significant challenges: narrowing down the almost infinite set of adjectives and answering the more basic question of why people have particular traits and whether they arise from biological or hereditary foundations.

Traits as Behavioral Dispositions and Motives

How might traits explain behavior?

One way to think about personality is as a combination of traits. This was the approach of Gordon Allport (1937), one of the first trait theorists, who believed people could be described in terms of traits just as an object could be described in terms of its properties. He saw a trait as a relatively stable disposition to behave in a particular and consistent way. For example, a person who keeps his books organized alphabetically in bookshelves, hangs his clothing neatly in the closet, knows the schedule for the local bus, keeps a clear agenda in a daily planner, and lists birthdays of friends and family in his calendar can be said to have the trait of orderliness. This trait consistently manifests itself in a variety of settings.

The orderliness trait describes a person but doesn’t explain his or her behavior. Why does the person behave in this way? There are two basic ways in which a trait might serve as an explanation: The trait may be a preexisting disposition of the person that causes the person’s behavior, or it may be a motivation that guides the person’s behavior. Allport saw traits as preexisting dispositions, causes of behavior that reliably trigger the behavior. The person’s orderliness, for example, is an inner property of the person that will cause the person to straighten things up and be tidy in a wide array of situations. Other personality theorists, such as Henry Murray (the creator of the TAT), suggested instead that traits reflect motives. Just as a hunger motive might explain someone’s many trips to the snack bar, a need for orderliness might explain the neat closet, organized calendar, and familiarity with the bus schedule (Murray & Kluckhohn, 1953). Researchers examining traits as causes have used personality inventories to measure them, whereas those examining traits as motives have more often used projective tests.

477

Researchers have described and measured hundreds of different personality traits over the past several decades. Back in the 1940s, in the wake of World War II, psychologists were very interested in right-

The Search for Core Traits

Picking a fashionable trait and studying it in depth doesn’t get us very far in the search for the core of human character: the basic set of traits that defines how humans differ from one another. People may differ strongly in their choice of Coke versus Pepsi, or dogs versus cats, but are these differences important? How have researchers tried to discover the core personality traits?

Classification Using Language

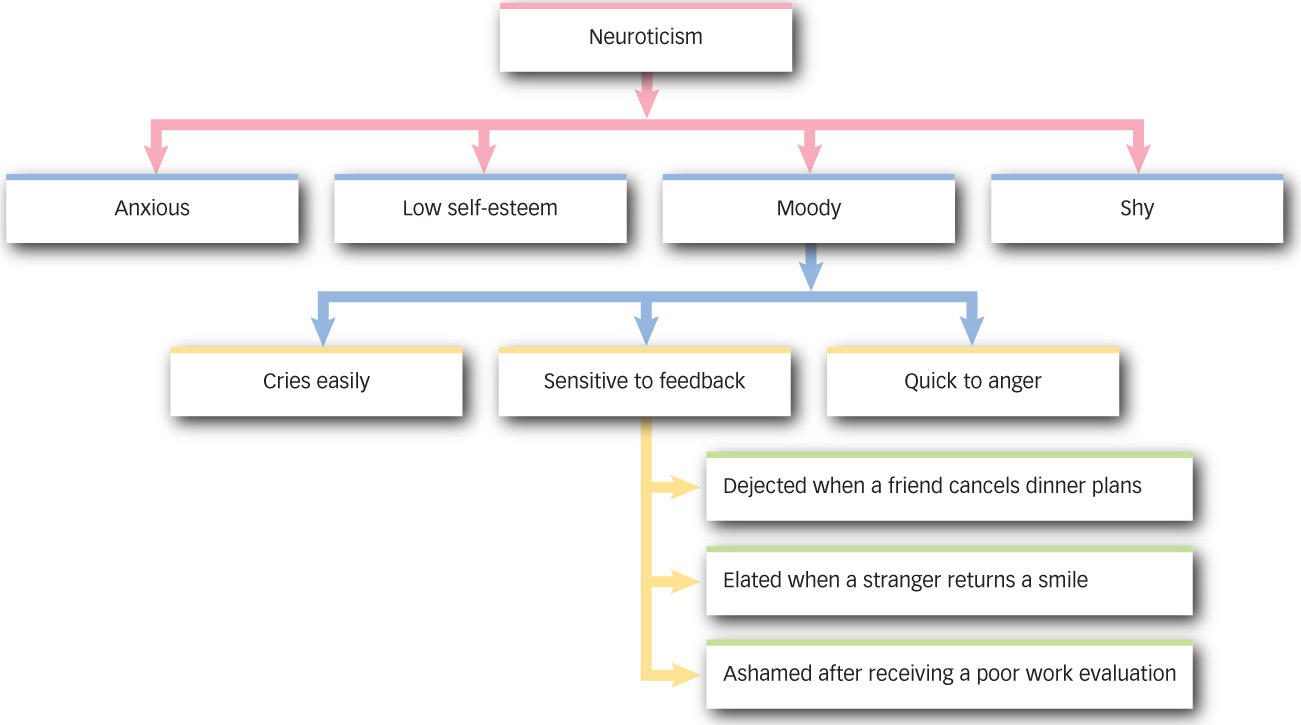

The study of core traits began with an exploration of how personality is represented in the store of wisdom we call language. Generation after generation, people have described people with words, so early psychologists proposed that core traits could be discerned by finding the main themes in all the adjectives used to describe personality. In one such analysis, a painstaking count of relevant words in a dictionary of English resulted in a list of over 18,000 potential traits (Allport & Odbert, 1936)! Attempts to narrow down the list to a more manageable set depend on the idea that traits might be related in a hierarchical pattern (see FIGURE 12.3), with more general or abstract traits at higher levels than more specific or concrete traits. Perhaps the more abstract traits represent the core of personality.

How do psychologists identify the core personality traits?

To identify this core, researchers have used the computational procedure called factor analysis, described in the Intelligence chapter, which sorts trait terms or self-

478

Figure 12.3: Hierarchical Structure of Traits Traits may be organized in a hierarchy in which many specific behavioral tendencies are associated with a higher-

Figure 12.3: Hierarchical Structure of Traits Traits may be organized in a hierarchy in which many specific behavioral tendencies are associated with a higher-Different factor analysis techniques have yielded different views of personality structure. Cattell (1950) proposed a 16-

The Big Five Dimensions of Personality

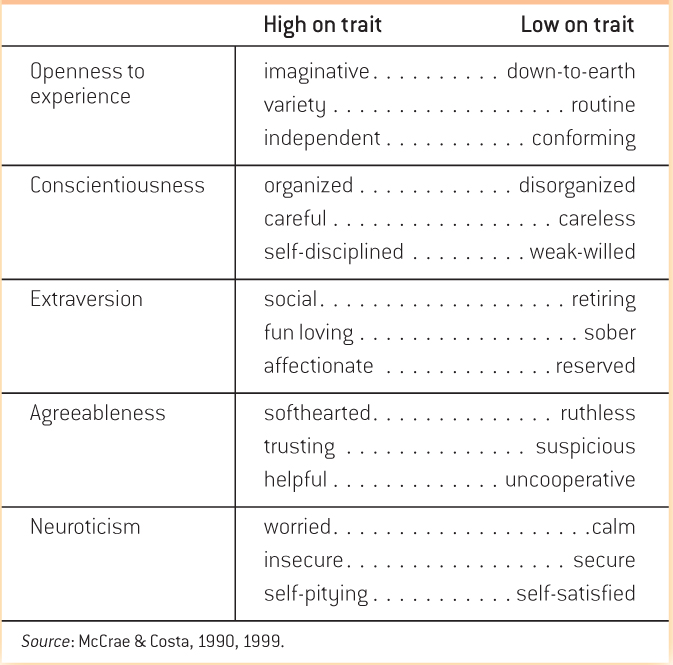

Today most researchers agree that personality is best captured by 5 factors rather than 2, 3, 16, or 18,000 (John & Srivastava, 1999; McCrae & Costa, 1999). The Big Five, as they are affectionately called, are the traits of the five-

What are the strengths of the five-

479

In fact, the Big Five dimensions are so universal that they show up even when people are asked to evaluate the traits of complete strangers (Passini & Norman, 1966). This finding suggests that these dimensions of personality might reside in the eye of the beholder: categories that people use to evaluate others regardless of how well they know them. However, it’s not all perception. The reality of these traits has been clearly established in research showing that self-

HOT SCIENCE: Personality on the Surface

When you judge someone as friend or foe, interesting or boring, worth hiring or firing, how do you do it? It’s nice to think that your impressions of personality are based on solid foundations—

It turns out that you can get some accurate information about a book by judging its cover. Recent studies have shown that extraverts smile more than others and appear more stylish and healthy (Naumann et al., 2009), and people high in openness to experience are more likely to have tattoos and other body modifications (Nathanson, Paulhus, & Williams, 2006). Findings like these suggest that people can manipulate their surface identities to try to make desired impressions on others, and that surface signs of personality might therefore be false or misleading. However, one recent study of people’s Facebook pages, which are clearly surface expressions of personality intended for others to see, found that the personalities people project online are more highly related to their real personalities than to the personalities they describe as their ideals (Back et al., 2010). The signs of personality that appear on the surface may be more than skin deep.

Going one step further, it turns out that people’s Facebook activity is significantly associated with their self-

480

Interestingly, research on the Big Five has shown that people’s personalities tend to remain fairly stable through their lifetime: Scores at one time in life correlate strongly with scores at later dates, even decades later (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). William James offered the opinion that “in most of us, by the age of thirty, the character has set like plaster, and will never soften again” (James, 1890, 121), but this turns out to be too strong a view. Some variability is typical in childhood, and though there is less in adolescence, some personality change can even occur in adulthood for some people (Srivistava et al., 2003).

Traits as Biological Building Blocks

Can we explain why a person has a stable set of personality traits? Many trait theorists have argued that unchangeable brain and biological processes produce the remarkable stability of traits over the life span. Allport viewed traits as characteristics of the brain that influence the way people respond to their environment. And, as you will see, Eysenck searched for a connection between his trait dimensions and specific individual differences in the workings of the brain.

Brain damage certainly can produce personality change, as the classic case of Phineas Gage so vividly demonstrates (see the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter). You may recall that after the blasting accident that blew a steel rod through his frontal lobes, Gage showed a dramatic loss of social appropriateness and conscientiousness (Damasio, 1994). In fact, when someone experiences a profound change in personality, testing often reveals the presence of such brain pathologies as Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, or brain tumor (Feinberg, 2001). The administration of antidepressant medication and other pharmaceutical treatments that change brain chemistry also can trigger personality changes, making people, for example, somewhat more extraverted and less neurotic (Bagby et al., 1999; Knutson et al., 1998).

Genes, Traits, and Personality

What do studies of twins tell us about personality?

Some of the most compelling evidence for the importance of biological factors in personality comes from the domain of behavioral genetics. Like researchers studying genetic influences on intelligence (see the Intelligence chapter), personality psychologists have looked at correlations between the traits in monozygotic, or identical, twins, who share the same genes, and dizygotic, or fraternal, twins, who on average share only half of their genes. The evidence has been generally consistent: In one review of studies involving over 24,000 twin pairs, for example, identical twins proved markedly more similar to each other in personality than did fraternal twins (Loehlin, 1992).

| Trait Dimension | Heritability |

|---|---|

| Openness | .45 |

| Conscientiousness | .38 |

| Extraversion | .49 |

| Agreeableness | .35 |

| Neuroticism | .41 |

| Source: Loehlin, 1992. | |

Simply put, the more genes you have in common with someone, the more similar your personalities are likely to be. Genes seem to influence most personality traits, and current estimates place the average genetic component of personality in the range of .40 to .60. These heritability coefficients, as you learned in the Intelligence chapter, indicate that roughly half the variability among individuals results from genetic factors (Bouchard & Loehlin, 2001). Of course, genetic factors do not account for everything and the remaining half of the variability in personality remains to be explained by differences in life experiences and other factors (see also the Real World box). Studies of twins suggest that the extent to which the Big Five traits derive from genetic differences ranges from .35 to .49 (see TABLE 12.3).

As in the study of intelligence, potential confounding factors must be ruled out to ensure that effects are truly due to genetics and not to environmental experiences. Are identical twins treated more similarly, and do they have a greater shared environment than fraternal twins? As children, were they dressed in the same snappy outfits and placed on the same Little League teams, and could this somehow have produced similarities in their personalities? Studies of identical twins reared far apart in adoptive families—

481

THE REAL WORLD: Are There “Male” and “Female” Personalities?

Do you think there is a typical female personality or a typical male personality? Researchers have found some reliable differences between men and women with respect to their self-

Although the gender differences in personality are quite small, they tend to get a lot of attention. There is debate about the origins of gender differences in personality, which often involves contrasting an evolutionary biological perspective with a social-

According to social role theory, personality characteristics and behavioral differences between men and women result from cultural standards and expectations that assign them: socially permissible jobs, activities, and family positions (Eagly & Wood, 1999). Because of their physical size and their freedom from childbearing, men historically took roles of greater power—

Regardless of the source of gender differences in personality, the degree to which people identify personally with masculine and feminine stereotypes may tell us about important personality differences between individuals. Sandra Bem (1974) designed a scale (the Bem Sex Role Inventory) that assesses the degree of identification with stereotypically masculine and feminine traits. Bem suggested that psychologically androgynous people (those who adopt the best of both worlds and identify with positive feminine traits such as kindness and positive masculine traits such as assertiveness) might be better adjusted than people who identify strongly with only one sex role.

An interesting wrinkle to this whole story is that although personality traits are fairly stable, they do shift a bit over time. In general, people become more conscientious in their 20s (got to keep that job!), and more agreeable in their 30s (got to keep those friends!). Neuroticism decreases with age, but only among women (Srivastava et al., 2003). So enjoy the personality you have now, because it may be changing soon.

Bem Sex Role Inventory Sample Items

| Masculine items | Feminine items |

|---|---|

| Self- |

Yielding |

| Defends own beliefs | Affectionate |

| Independent | Flatterable |

| Assertive | Sympathetic |

| Forceful | Sensitive to the needs of others |

482

Indeed, one provocative, related finding is that such shared environmental factors as parental divorce or parenting style may have little direct impact on personality (Plomin & Caspi, 1999). According to these researchers, simply growing up in the same family does not make people very similar. In fact, when two siblings are similar, this is thought to be primarily due to genetic similarities.

Researchers also have assessed specific behavioral and attitude similarities in twins, and the evidence for heritability in these studies is often striking. One study that examined 3,000 pairs of identical and fraternal twins found evidence for the genetic transmission of conservative views regarding topics such as socialism, church authority, the death penalty, and mixed-

Do Animals Have Personalities?

Another source of evidence for the biological basis of human personality comes from the study of nonhuman animals. Any dog owner, zookeeper, or cattle farmer can tell you that individual animals have characteristic patterns of behavior. One Missouri woman who reportedly enjoyed raising chickens in her suburban home said that “the best part” was “knowing them as individuals” (Tucker, 2003). As far as we know, this pet owner did not give her feathered companions a personality test, though researcher Sam Gosling (1998) used this approach in a study of a group of spotted hyenas. Well, not exactly. He recruited four human observers to use personality scales to rate the different hyenas in the group. When he examined ratings on the scales, he found five dimensions; three closely resembled the Big Five traits of neuroticism (i.e., fearfulness, emotional reactivity), openness to experience (i.e., curiosity), and agreeableness (i.e., absence of aggression).

In similar studies of guppies and octopi, individual differences in traits resembling extraversion and neuroticism were reliably observed (Gosling & John, 1999). In each study, researchers identified particular behaviors that they felt reflected each trait based on their observation of the animals’ normal repertoire of activities. Octopi, for example, seldom get invited to parties, so they cannot be assessed for their socializing tendencies (“He was all hands!”), but they do vary in terms of whether they prefer to eat in the safety of their den or are willing to venture out at feeding time, and so a behavior that corresponds to extraversion can reasonably be assessed (Gosling & John, 1999). Because different observers seem to agree on where an animal falls on a given dimension, the findings do not simply reflect a particular observer’s imagination or tendency to anthropomorphize (i.e., to attribute human characteristics to nonhuman animals). Such findings of cross-

Why study animal behavioral styles?

483

From an evolutionary perspective, differences in personality reflect alternative adaptations that species—

Traits in the Brain

What neurological differences explain why extraverts pursue more stimulation than introverts?

What neurophysiological mechanisms might influence the development of personality traits? Much of the thinking on this topic has focused on the extraversion–introversion dimension. In his personality model, Eysenck (1967) speculated that extraversion and introversion might arise from individual differences in cortical arousal. Eysenck suggested that extraverts pursue stimulation because their reticular formation (the part of the brain that regulates arousal or alertness, as described in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter) is not easily stimulated. To achieve greater cortical arousal and feel fully alert, Eysenck argued, extraverts seek out social interaction, parties, and other activities to achieve mental stimulation. In contrast, introverts may prefer reading or quiet activities because their cortex is very easily stimulated to a point higher than optimal alertness.

Behavioral and physiological research generally supports Eysenck’s view. When introverts and extraverts are presented with a range of intense stimuli, introverts respond more strongly, including salivating more when a drop of lemon juice is placed on their tongues and reacting more negatively to electric shocks or loud noises (Bartol & Costello, 1976; Stelmack, 1990). This reactivity has an impact on the ability to concentrate: Extraverts tend to perform well at tasks that are done in a noisy, arousing context (such as bartending or teaching), whereas introverts are better at tasks that require concentration in tranquil contexts (such as the work of a librarian or nighttime security guard; Geen, 1984; Lieberman & Rosenthal, 2001; Matthews & Gilliland, 1999).

In a refined version of Eysenck’s ideas about arousability, Jeffrey Gray (1970) proposed that the dimensions of extraversion–introversion and neuroticism reflect two basic brain systems. The behavioral activation system (BAS), essentially a “go” system, activates approach behavior in response to the anticipation of reward. The extravert has a highly reactive BAS and will actively engage the environment, seeking social reinforcement and be on the go. The behavioral inhibition system (BIS), a “stop” system, inhibits behavior in response to stimuli signaling punishment. The anxious person, in turn, has a highly reactive BIS and will focus on negative outcomes and be on the lookout for stop signs. Because these two systems operate independently, it is possible for someone to be both a go and a stop person (simultaneously activated and inhibited), caught in a constant conflict between these two traits. Studies of brain electrical activity (EEG) and functional brain imaging (fMRI) suggest that individual differences in activation and inhibition arise through the operation of distinct brain systems underlying these tendencies (DeYoung & Gray, 2009). Even more recently, studies have suggested that the core personality traits described above may arise from individual differences in the volume of the different brain regions associated with each trait. For instance, self-

484

The trait approach tries to identify personality dimensions that can be used to characterize an individual’s behavior. Researchers have attempted to boil down the potentially huge array of things people do, think, and feel into some core personality dimensions.

The trait approach tries to identify personality dimensions that can be used to characterize an individual’s behavior. Researchers have attempted to boil down the potentially huge array of things people do, think, and feel into some core personality dimensions. Many personality psychologists currently focus on the Big Five personality factors: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

Many personality psychologists currently focus on the Big Five personality factors: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. To address the question of why traits arise, trait theorists often adopt a biological perspective, seeing personality largely as the result of genetic influences on brain functioning.

To address the question of why traits arise, trait theorists often adopt a biological perspective, seeing personality largely as the result of genetic influences on brain functioning.