12.3 The Psychodynamic Approach: Forces That Lie beneath Awareness

Rather than trying to understand personality in terms of broad theories for describing individual differences, Freud looked for personality in the details: the meanings and insights revealed by careful analysis of the tiniest blemishes in a person’s thought and behavior. Working with patients who came to him with disorders that did not seem to have any physical basis, he began by interpreting the origins of their everyday mistakes and memory lapses, errors that have come to be called Freudian slips.

Freud used the term psychoanalysis to refer to both his theory of personality and his method of treating patients. Freud’s ideas were the first of many theories building on his basic idea that personality is a mystery to the person who “owns” it because we can’t know our own deepest motives. The theories of Freud and his followers (discussed in the Treatment chapter) are referred to as the psychodynamic approach, an approach that regards personality as formed by needs, strivings, and desires largely operating outside of awareness—

485

Psychologists call this construct the dynamic unconscious, an active system encompassing a lifetime of hidden memories, the person’s deepest instincts and desires, and the person’s inner struggle to control those forces. The power of the unconscious is believed to come from its early origins—

The Structure of the Mind: Id, Ego, and Superego

To explain the emotional difficulties that beset his patients, Freud proposed that the mind consists of three independent, interacting, and often conflicting systems: the id, the superego, and the ego.

The most basic system, the id, is the part of the mind containing the drives present at birth; it is the source of our bodily needs, wants, desires, and impulses, particularly our sexual and aggressive drives. The id operates according to the pleasure principle, the psychic force that motivates the tendency to seek immediate gratification of any impulse. If governed by the id alone, you would never be able to tolerate the buildup of hunger while waiting to be served at a restaurant but would simply grab food from tables nearby.

Opposite the id is the superego, the mental system that reflects the internalization of cultural rules, mainly learned as parents exercise their authority. The superego consists of a set of guidelines, internal standards, and other codes of conduct that regulate and control our behaviors, thoughts, and fantasies. It acts as a kind of conscience, punishing us when it finds we are doing or thinking something wrong (by producing guilt or other painful feelings) and rewarding us (with feelings of pride or self-

According to Freud, how is personality shaped by the interaction of the id, superego, and ego?

The final system of the mind, according to psychoanalytic theory, is the ego, the component of personality, developed through contact with the external world, that enables us to deal with life’s practical demands. The ego operates according to the reality principle, the regulating mechanism that enables the individual to delay gratifying immediate needs and function effectively in the real world. It is the mediator between the id and the superego. The ego helps you resist the impulse to snatch others’ food and also finds the restaurant and pays the check.

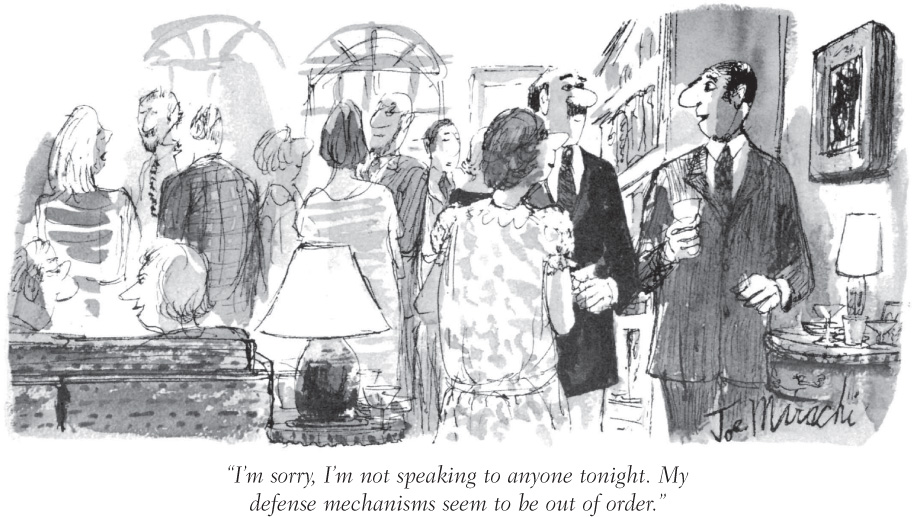

| Repression is the first defense the ego tries, but if it is inadequate, then other defense mechanisms may come into play. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Defense Mechanism | Description | Example |

| Repression | Removing painful experiences and unacceptable impulses from the conscious mind: “motivated forgetting.” | Not lashing out physically in anger; putting a bad experience out of your mind. |

| Rationalization | Supplying a reasonable sounding explanation for unacceptable feelings and behavior to conceal (mostly from oneself) one’s underlying motives or feelings. | Dropping calculus “allegedly” because of poor ventilation in the classroom. |

| Reaction formation | Unconsciously replacing threatening inner wishes and fantasies with an exaggerated version of their opposite. | Being rude to someone you’re attracted to. |

| Projection | Attributing one’s own threatening feelings, motives, or impulses to another person or group. | Judging others as being dishonest because you believe that you are dishonest. |

| Regression | Reverting to an immature behavior or earlier stage of development, a time when things felt more secure, to deal with internal conflict and perceived threat. | Using baby talk, even though able to use appropriate speech, in response to distress. |

| Displacement | Shifting unacceptable wishes or drives to a neutral or less threatening alternative. | Slamming a door; yelling at someone other than the person you’re mad at. |

| Identification | Dealing with feelings of threat and anxiety by unconsciously taking on the characteristics of another person who seems more powerful or better able to cope. | A bullied child becoming a bully. |

| Sublimation | Channeling unacceptable sexual or aggressive drives into socially acceptable and culturally enhancing activities. | Diverting anger to the football or rugby field, or other contact sport. |

Freud believed that the relative strength of the interactions among the three systems of mind (i.e., which system is usually dominant) determines an individual’s basic personality structure. Together the id force of personal needs, the superego force of pressures to quell those needs, and the ego force of reality’s demands create constant internal conflict. He believed that the dynamics among the id, superego, and ego are largely governed by anxiety, an unpleasant feeling that arises when unwanted thoughts or feelings occur, such as when the id seeks a gratification that the ego thinks will lead to real-

486

487

Psychosexual Stages and the Development of Personality

Freud also proposed that a person’s basic personality is formed before 6 years of age during a series of sensitive periods, or life stages, when experiences influence all that will follow. Freud called these periods psychosexual stages, distinct early life stages through which personality is formed as children experience sexual pleasures from specific body areas and caregivers redirect or interfere with those pleasures. He argued that as a result of adult interference with pleasure-

Problems and conflicts encountered at any psychosexual stage, Freud believed, will influence personality in adulthood. Conflict resulting from a person’s being deprived or, paradoxically, overindulged at a given stage could result in fixation, a phenomenon in which a person’s pleasure-

In the 1st year and a half of life, the infant is in the oral stage, the first psychosexual stage, in which experience centers on the pleasures and frustrations associated with the mouth, sucking, and being fed. Infants who are deprived of pleasurable feeding or indulgently overfed are believed to have a personality style in which they are focused on issues related to fullness and emptiness and what they can “take in” from others.

In the 1st year and a half of life, the infant is in the oral stage, the first psychosexual stage, in which experience centers on the pleasures and frustrations associated with the mouth, sucking, and being fed. Infants who are deprived of pleasurable feeding or indulgently overfed are believed to have a personality style in which they are focused on issues related to fullness and emptiness and what they can “take in” from others. Between 2 and 3 years of age, the child moves on to the anal stage, the second psychosexual stage, in which experience is dominated by the pleasures and frustrations associated with the anus, retention and expulsion of feces and urine, and toilet training. Individuals who have had difficulty negotiating this conflict are believed to develop a rigid personality and remain preoccupied with issues of control.

Between 2 and 3 years of age, the child moves on to the anal stage, the second psychosexual stage, in which experience is dominated by the pleasures and frustrations associated with the anus, retention and expulsion of feces and urine, and toilet training. Individuals who have had difficulty negotiating this conflict are believed to develop a rigid personality and remain preoccupied with issues of control. Between the ages of 3 and 5 years, the child is in the phallic stage, the third psychosexual stage, in which experience is dominated by the pleasure, conflict, and frustration associated with the phallic–genital region as well as coping with powerful incestuous feelings of love, hate, jealousy, and conflict. According to Freud, children in the phallic stage experience the Oedipus conflict, a developmental experience in which a child’s conflicting feelings toward the opposite-

Between the ages of 3 and 5 years, the child is in the phallic stage, the third psychosexual stage, in which experience is dominated by the pleasure, conflict, and frustration associated with the phallic–genital region as well as coping with powerful incestuous feelings of love, hate, jealousy, and conflict. According to Freud, children in the phallic stage experience the Oedipus conflict, a developmental experience in which a child’s conflicting feelings toward the opposite-sex parent are (usually) resolved by identifying with the same- .sex parent  A more relaxed period in which children are no longer struggling with the power of their sexual and aggressive drives occurs between the ages of 5 and 13, as children experience the latency stage, the fourth psychosexual stage, in which the primary focus is on the further development of intellectual, creative, interpersonal, and athletic skills. Because Freud believed that the most significant aspects of personality development occur before the age of 6 years, psychodynamic psychologists do not speak of fixation at the latency period. Simply making it to the latency period relatively undisturbed by conflicts of the earlier stages is a sign of healthy personality development.

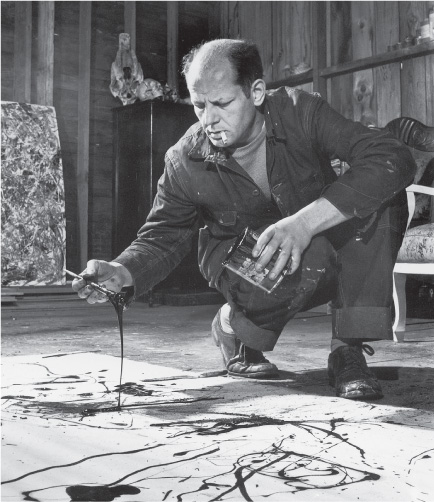

A more relaxed period in which children are no longer struggling with the power of their sexual and aggressive drives occurs between the ages of 5 and 13, as children experience the latency stage, the fourth psychosexual stage, in which the primary focus is on the further development of intellectual, creative, interpersonal, and athletic skills. Because Freud believed that the most significant aspects of personality development occur before the age of 6 years, psychodynamic psychologists do not speak of fixation at the latency period. Simply making it to the latency period relatively undisturbed by conflicts of the earlier stages is a sign of healthy personality development. One of the id’s desires is to make a fine mess (a desire that is often frustrated early in life, perhaps during the anal stage). Famous painter Jackson Pollock found a way to make extraordinarily fine messes—

One of the id’s desires is to make a fine mess (a desire that is often frustrated early in life, perhaps during the anal stage). Famous painter Jackson Pollock found a way to make extraordinarily fine messes—behavior that at some level all of us envy. MARTHA HOLMES//TIME LIFE

PICTURES/GETTY IMAGES At puberty and thereafter, the fifth and final stage of personality development occurs. The genital stage is the time for the coming together of the mature adult personality with a capacity to love, work, and relate to others in a mutually satisfying and reciprocal manner. Freud believed that people who are fixated in a prior stage fail to develop healthy adult sexuality and a well-

At puberty and thereafter, the fifth and final stage of personality development occurs. The genital stage is the time for the coming together of the mature adult personality with a capacity to love, work, and relate to others in a mutually satisfying and reciprocal manner. Freud believed that people who are fixated in a prior stage fail to develop healthy adult sexuality and a well-adjusted adult personality.

Why do critics say Freud’s psychosexual stages are more interpretation than explanation?

What should we make of all this? On the one hand, the psychoanalytic theory of psychosexual stages offers an intriguing picture of early family relationships and the extent to which they allow the child to satisfy basic needs and wishes. On the other hand, critics argue that psychodynamic explanations lack any real evidence and tend to focus on provocative after-

Freud believed that the personality results from forces that are largely unconscious, shaped by the interplay among id, superego, and ego.

Freud believed that the personality results from forces that are largely unconscious, shaped by the interplay among id, superego, and ego. Defense mechanisms are methods the mind may use to reduce anxiety generated from unacceptable impulses.

Defense mechanisms are methods the mind may use to reduce anxiety generated from unacceptable impulses. Freud also believed that the developing person passes through a series of psychosexual stages and that failing to progress beyond one of the stages results in fixation, which is associated with corresponding personality traits.

Freud also believed that the developing person passes through a series of psychosexual stages and that failing to progress beyond one of the stages results in fixation, which is associated with corresponding personality traits.