13.1 Social Behavior: Interacting with People

Centipedes aren’t social. Neither are snails or brown bears. In fact, most animals are loners who prefer solitude to company. So why don’t we?

All animals must survive and reproduce, and being social is one strategy for accomplishing these two important goals. When it comes to finding food or fending off enemies, herds and packs and flocks can often do what individuals can’t, and that’s why over millions of years many different species have found it useful to become social. But of the thousands and thousands of social species on our planet, only four have become ultrasocial, which means that they form societies in which large numbers of individuals divide labor and cooperate for mutual benefit. Those four species are the hymenoptera (i.e., ants, bees, and wasps), the termites, the naked mole rats, and us (Haidt, 2006). Even in this fine company we distinguish ourselves, because only we form societies of genetically unrelated individuals. Indeed, some scientists believe that the complexity of living in large social groups is the primary reason why nature endowed us with such big brains (Sallet et al., 2011; Shultz & Dunbar, 2010; Smith et al., 2010). If 10,000 years ago you had rounded up all the mammals on Earth and placed them on a gigantic bathroom scale, human beings would have accounted for about 0.01% of the total mass, but today we would account for 98%. We are the heavyweight champions of survival and reproduction because we are deeply social, and as you are about to see, much of our social behavior revolves around these two basic goals.

Survival: The Struggle for Resources

Animals have a problem: survival. To survive, animals must find resources such as food, water, and shelter. The problem is that these resources are necessarily scarce, because if they weren’t, then the population would increase until they were. Animals often solve this problem by hurting or helping each other. Hurting and helping are antonyms and you might expect them to have little in common, but as you will see, these disparate behaviors are actually two solutions to the same problem (Hawley, 2002).

Aggression

The simplest way to solve the problem of scarce resources is to take those resources and then kick the stuffing out of anyone who tries to stop you. Aggression is behavior with the purpose of harming another (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Bushman & Huesmann, 2010), and it is a strategy used by just about every animal on the planet. Aggression is not something that animals do for its own sake but, rather, as a way of getting the resources they need. The frustration-aggression hypothesis suggests that animals aggress when their desires are frustrated (Dollard et al., 1939). The chimp wants the banana (desire) but the pelican is about to take it (frustration), so the chimp threatens the pelican with its fist (aggression). The robber wants the money (desire) but the teller has it all locked up (frustration), so the robber threatens the teller with a gun (aggression).

509

The frustration–aggression hypothesis is right as far as it goes, but many scientists think it doesn’t go far enough. They argue that the cause of aggressive behavior is negative affect (more commonly known as feeling bad) and that a frustrated desire is just one of many things that might induce negative affect (Berkowitz, 1990). If animals aggress when they feel bad, then anything that makes them feel bad should increase aggression—

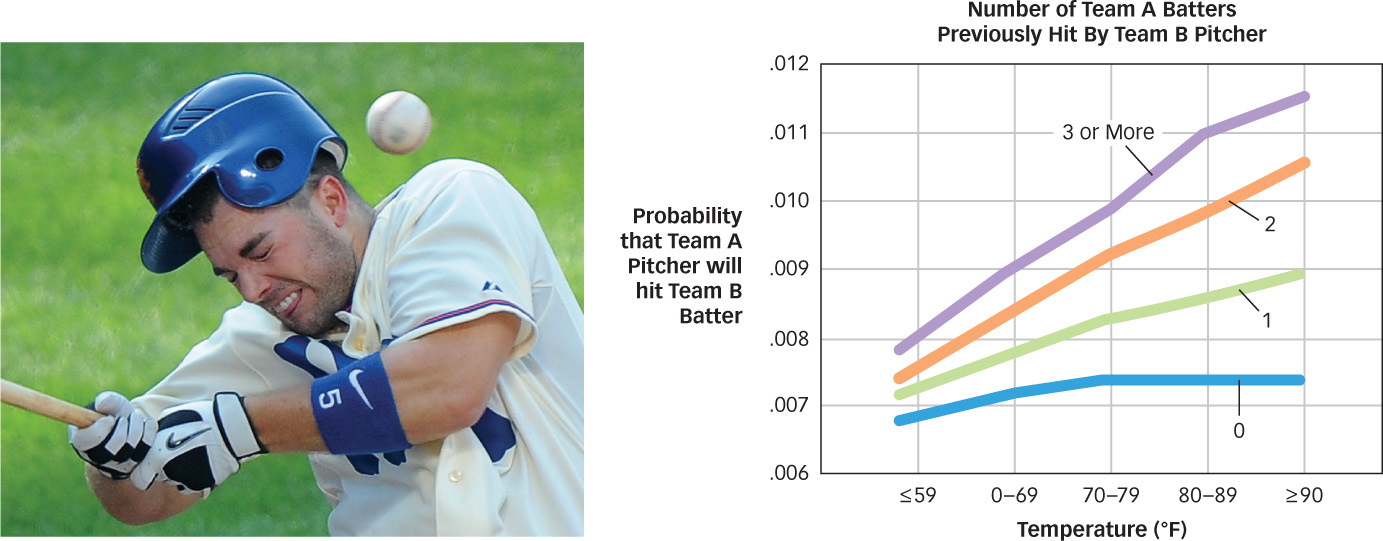

Figure 13.1: Hot and Bothered Professional pitchers have awfully good aim, so when they hit batters with the baseball, it’s safe to assume that it wasn’t an accident. This graph shows data from nearly 60,000 major league baseball games. As you can see, as the temperature on the field increases, so does the likelihood that Team A batters will be hit by Team B pitchers. This effect becomes even stronger when Team B batters have previously been hit by Team A pitchers, suggesting that the Team B pitcher is seeking revenge (Larrick et al., 2011).

Figure 13.1: Hot and Bothered Professional pitchers have awfully good aim, so when they hit batters with the baseball, it’s safe to assume that it wasn’t an accident. This graph shows data from nearly 60,000 major league baseball games. As you can see, as the temperature on the field increases, so does the likelihood that Team A batters will be hit by Team B pitchers. This effect becomes even stronger when Team B batters have previously been hit by Team A pitchers, suggesting that the Team B pitcher is seeking revenge (Larrick et al., 2011).

LARICK, R. P., TIMERMAN, T. A., CARTON, A. M., & ABREVAYA, J., PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE, 22(4), PP. 423–428, COPYRIGHT © 2011 BY SAGE PUBLICATIONS. REPRINTED BY PERMISSION OF SAGE PUBLICATIONS.

Of course, not everyone aggresses every time they feel bad. So who does and why? Research suggests that both biology and culture play important roles in determining if and when people will aggress.

Biology and Aggression. If you wanted to know whether someone was likely to engage in aggression and you could ask them just one question, it should be “Are you male or female?” (Wrangham & Peterson, 1997). Crimes such as assault, battery, and murder are almost exclusively perpetrated by men—

510

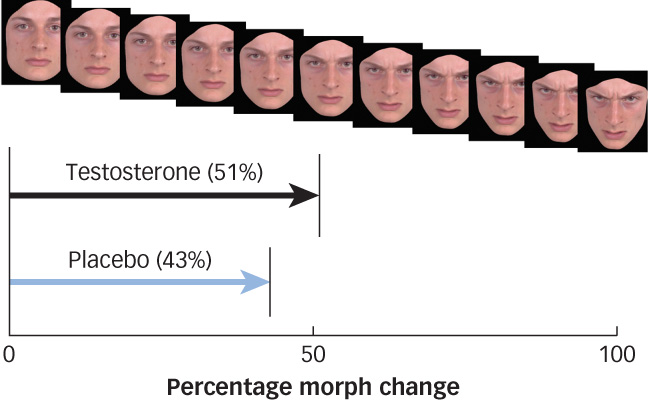

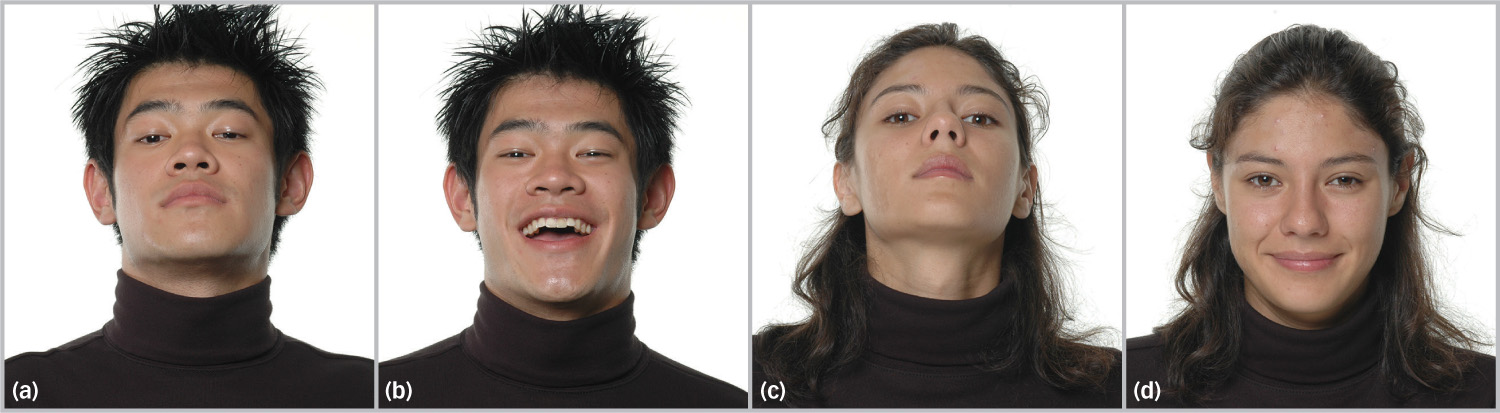

Testosterone doesn’t directly cause aggression, but rather, seems to make people feel powerful and confident in their ability to prevail (Eisenegger et al., 2010; Eisenegger, Haushofer, & Fehr, 2011). Male chimpanzees with high testosterone tend to stand tall and hold their chins high (Muller & Wrangham, 2004), and human beings with high testosterone walk more purposefully, focus more directly on the people they are talking to, and speak in a more forward and independent manner (Dabbs et al., 2001). Testosterone also makes people more sensitive to provocation (Ronay & Galinsky, 2011) and less sensitive to signs of retaliation. Participants in one experiment watched a face as its expression changed from neutral to threatening and were asked to respond as soon as the expression became threatening (see FIGURE 13.2). Participants who were given a small dose of testosterone before the experiment were slower to recognize the threatening expression (van Honk & Schutter, 2007). Failing to recognize that the person you are criticizing is getting angry is a good way to end up in a fight.

Figure 13.2: I Spy Threat Subjects who were given testosterone needed to see a more threatening expression before they were able to recognize it as such (van Honk & Schutter, 2007).

Figure 13.2: I Spy Threat Subjects who were given testosterone needed to see a more threatening expression before they were able to recognize it as such (van Honk & Schutter, 2007).

Under what circumstances do women aggress?

One of the most reliable ways to elicit aggression in males is to challenge their status or dominance. Indeed, three quarters of all murders can be classified as “status competitions” or “contests to save face” (Daly & Wilson, 1988). Contrary to popular wisdom, it isn’t men with low self-

Although women can be just as aggressive as men, their aggression tends to be more premeditated than impulsive and more likely to be focused on attaining or protecting a resource than on attaining or protecting their status. Women are much less likely than men to aggress without provocation or to aggress in ways that cause physical injury, but they are only slightly less likely than men to aggress when provoked or to aggress in ways that cause psychological injury (Bettencourt & Miller, 1996; Eagly & Steffen, 1986). Indeed, women may even be more likely than men to aggress by causing social harm, for example, by ostracizing others (Benenson et al., 2011) or by spreading malicious rumors about them (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995).

AP PHOTO/JERRY LARSON

511

Culture and Aggression. William James (1911, p. 272) wrote that “our ancestors have bred pugnacity into our bone and marrow and thousands of years of peace won’t breed it out of us.” Was he right? Although aggression is clearly part of our evolutionary heritage, that doesn’t mean it is inevitable. Indeed, the number of wars and the rate of murder have decreased by orders of magnitude in the last century alone. As psychologist Steven Pinker (2007) noted:,

What evidence suggests that culture can influence aggression?

We have been getting kinder and gentler. Cruelty as entertainment, human sacrifice to indulge superstition, slavery as a labor-

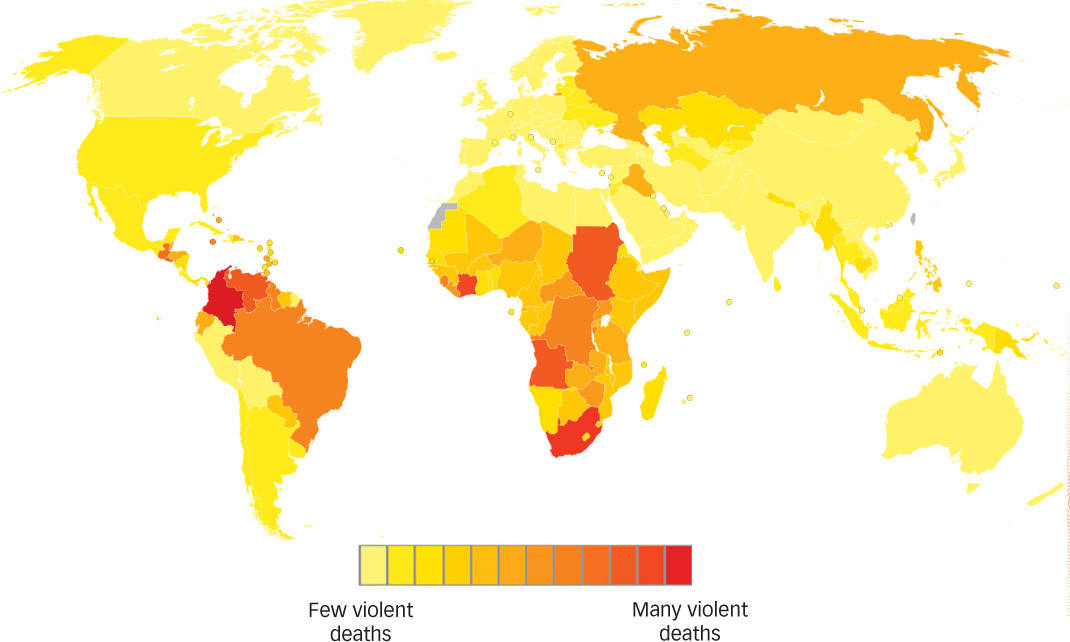

Just as aggression varies with time, so too does it vary with geography (see FIGURE 13.3). For example, violent crime in the United States is more prevalent in the South, where men are taught to react aggressively when they feel their status has been challenged (Brown, Osterman, & Barnes, 2009; Nisbett & Cohen, 1996). In one set of experiments, researchers insulted American volunteers from Northern and Southern states and found that Southerners were more likely to experience a surge of testosterone and to feel that their status had been diminished by the insult (Cohen et al., 1996). When a large man walked directly toward them as they were leaving the experiment, insulted Southerners got “right up in his face” before giving way, whereas Northerners just stepped aside. Of course, in the control condition in which participants were not insulted, Southerners stepped aside before Northerners did, which is to say that when they aren’t being insulted, Southerners are more polite than Northerners!

Figure 13.3: The Geography of Violence When it comes to violence, culture matters a lot. Interestingly, one factor that distinguishes between more and less violent nations is gender equality (Caprioli, 2003; Melander, 2005). The better a nation’s women are treated, the lower that nation’s likelihood of going to war.

Figure 13.3: The Geography of Violence When it comes to violence, culture matters a lot. Interestingly, one factor that distinguishes between more and less violent nations is gender equality (Caprioli, 2003; Melander, 2005). The better a nation’s women are treated, the lower that nation’s likelihood of going to war.

Variation over time and geography shows that culture can play an important role in determining whether our innate capacity for aggression will result in aggressive behavior (Leung & Cohen, 2011). People learn by example, which is why some researchers believe that watching violent television shows and playing violent video games can make people more aggressive (Anderson et al., 2010) and less cooperative (Sheese & Graziano, 2005; cf. Ferguson, 2010). But cultures can provide good examples as well as bad ones (Fry, 2012). In the mid-

512

AP PHOTO/MANISH SWARUP

Cooperation

Aggression is one way to solve the problem of scarce resources, but it is not the most inventive way, because when individuals work together they can often each get more resources than either could get alone. Cooperation is behavior by two or more individuals that leads to mutual benefit (Deutsch, 1949; Pruitt, 1998), and it is one of our species’ greatest achievements—

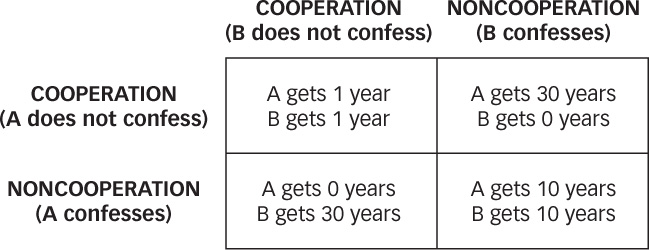

Risk and Trust. So if the benefits of cooperation are clear, then why don’t we cooperate all the time? Cooperation is potentially beneficial, but it is also risky, and a simple game called the prisoner’s dilemma illustrates why. Imagine that you and your friend have been arrested for hacking into your bank’s mainframe computer and directing a few million dollars to your personal accounts. You are now being interrogated separately. The detectives tell you that if you and your friend both confess, you’ll each get 10 years in prison for felony theft, and if you both refuse to confess, you’ll each get 1 year in prison for, oh say, disturbing the peace. However, if one of you confesses and the other doesn’t, then the one who confesses will go free and the one who doesn’t confess will be put away for 30 years. What should you do? If you study FIGURE 13.4, you’ll see that you and your friend would be wise to cooperate. If you trust your friend and refuse to confess, and if your friend trusts you and refuses to confess, then you will both get a light sentence. But look what happens if you trust your friend and then your friend double-

Figure 13.4: The Prisoner’s Dilemma Game The prisoner’s dilemma game illustrates the benefits and costs of cooperation. Players A and B receive benefits whose size depends on whether they independently decide to cooperate. Mutual cooperation leads to a relatively moderate benefit to both players, but if only one player cooperates, then the cooperator gets no benefit and the noncooperator gets a large benefit.

Figure 13.4: The Prisoner’s Dilemma Game The prisoner’s dilemma game illustrates the benefits and costs of cooperation. Players A and B receive benefits whose size depends on whether they independently decide to cooperate. Mutual cooperation leads to a relatively moderate benefit to both players, but if only one player cooperates, then the cooperator gets no benefit and the noncooperator gets a large benefit.

What makes cooperation risky?

513

The prisoner’s dilemma is more than a game. It mirrors the potential costs and benefits of cooperation in everyday life. For example, if everyone pays his or her taxes, then the tax rate stays low and everyone enjoys the benefits of sturdy bridges and first-

Life is a strategic game, and we value those who play it honorably and despise those who don’t. When people are asked what single trait they most want those around them to have, the answer is trustworthiness (Cottrell, Neuberg, & Li, 2007), and when those around us fail to demonstrate that quality we react bitterly. For example, the ultimatum game requires one player (the divider) to divide a monetary prize into two parts and offer one of the parts to a second player (the decider), who can either accept or reject the offer. If the decider rejects the offer, then both players get nothing and the game is over. Studies show that deciders typically reject offers that they consider unfair because they’d rather get nothing than get cheated (Fehr & Gaechter, 2002; Thaler, 1988). In other words, people will pay to punish someone who has treated them unfairly. Nonhumans also seem to dislike unfair treatment. In one study, monkeys were willing to work for a slice of cucumber until they saw the experimenter give another monkey a more delicious food for doing less work (Brosnan & DeWaal, 2003). At that point the first set of monkeys went on strike and refused to participate further.

Groups and Favoritism. Cooperation requires that we take a risk by benefiting those who have not yet benefited us and then trusting them to do the same. But whom can we trust?

What is the difference between prejudice and discrimination?

A group is a collection of people who have something in common that distinguishes them from others. Every one of us is a member of many groups—

What are the costs of groups?

514

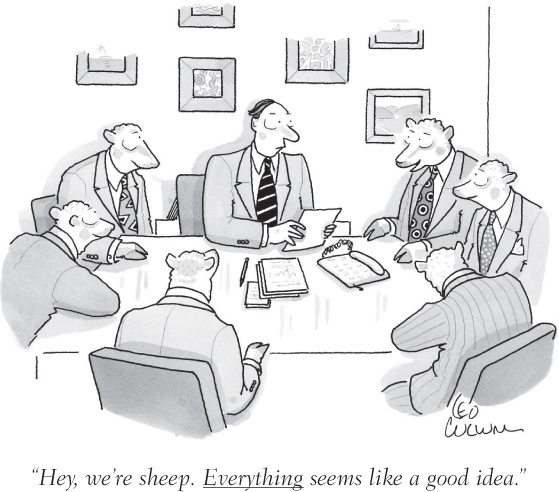

But if groups have benefits, they also have costs. For example, when groups try to make decisions, they rarely do better than the best member would have done alone—

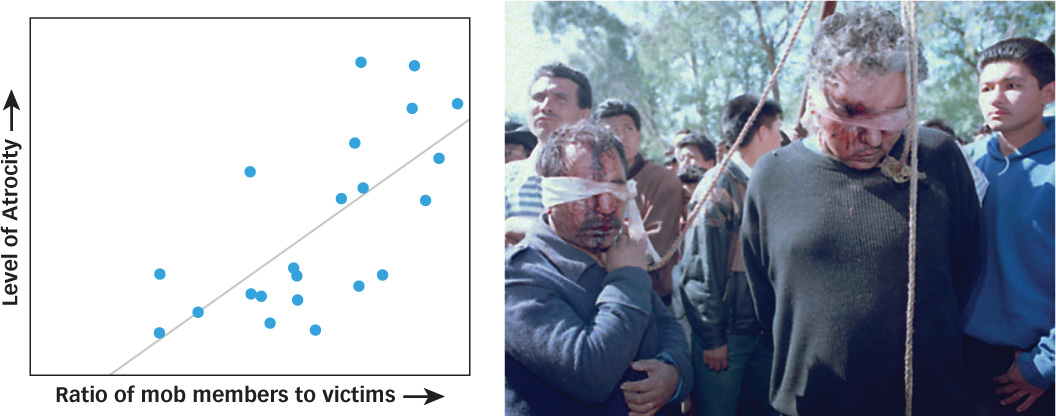

The costs of groups go beyond bad decisions because people in groups sometimes do terrible things that none of their members would do alone (Yzerbyt & Demoulin, 2010). Lynching, rioting, gang-

One reason is deindividuation, which occurs when immersion in a group causes people to become less concerned with their personal values. We may want to grab the Rolex from the jeweler’s window or plant a kiss on the attractive stranger in the library, but we don’t do these things because they conflict with our personal values. Research shows that people are most likely to consider their personal values when their attention is focused on themselves (Wicklund, 1975), and being assembled in groups draws our attention to others and away from ourselves. As a result, we are less likely to consider our own personal values and instead adopt the group’s values (Postmes & Spears, 1998).

A second reason why groups behave badly is diffusion of responsibility, which refers to the tendency for individuals to feel diminished responsibility for their actions when they are surrounded by others who are acting the same way. Diffusion of responsibility is the main culprit behind something you’ve probably observed many times—

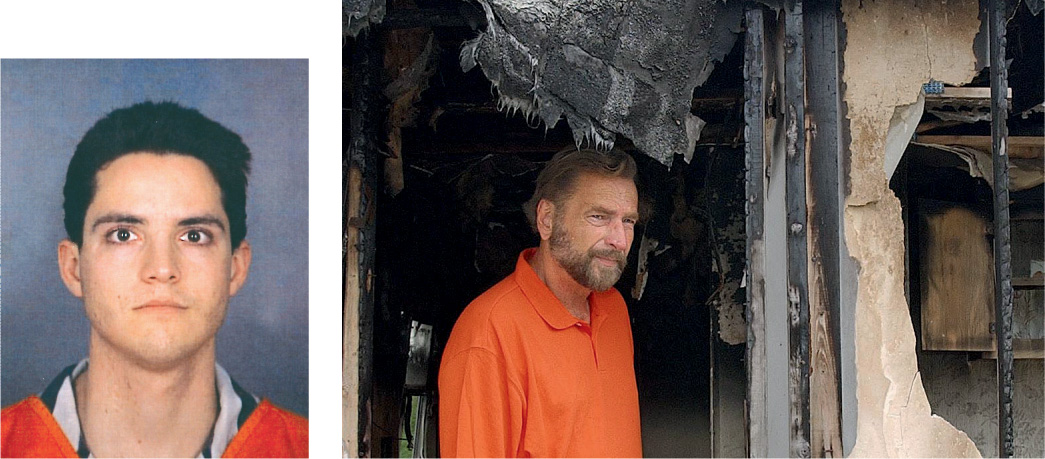

Figure 13.5: Mob Size and Level of Atrocity Groups are capable of horrible things. These two men were rescued by police just as residents of their town prepared to lynch them for stealing a car. Because larger groups provide more opportunity for deindividuation and diffusion of responsibility, their atrocities become more horrible as the ratio of mob members to victims becomes larger (Leader, Mullen, & Abrams, 2007).

Figure 13.5: Mob Size and Level of Atrocity Groups are capable of horrible things. These two men were rescued by police just as residents of their town prepared to lynch them for stealing a car. Because larger groups provide more opportunity for deindividuation and diffusion of responsibility, their atrocities become more horrible as the ratio of mob members to victims becomes larger (Leader, Mullen, & Abrams, 2007).

515

If groups make bad decisions and foster bad behavior, then might we be better off without them? Probably not. One of the best predictors of a person’s general well-

516

HOT SCIENCE: Mouse Over

How much would you pay to save a life? The answer may depend on whether the decision is yours alone. Genetics laboratories that breed mice for experiments often end up with surplus mice. Because it is so expensive to house and feed these mice for their entire life spans, surplus mice are typically killed. Researchers at the University of Bonn decided to see how much people would pay to keep just one surplus mouse alive (Falk & Szech, 2013). They offered participants 10 Euros (about $15) to participate in their study. After participants accepted, they showed them a picture of a mouse that was destined to be killed and told them that if they would give back the 10 Euros, it would be used to support the mouse for the rest of its natural life. The majority of participants—

But when the researchers put the mouse’s fate in the hands of two participants, the results changed dramatically. In a second condition of the study, the participants negotiated about what would happen to the mouse. Specifically, the participants were told that if they could agree on a way to split 20 Euros, then they would each receive the amount they agreed to and the mouse would die. If they could not agree on a way to split the money, then they would each receive nothing and the mouse would be allowed to live out its natural life. If a participant wanted the mouse to live, then all he or she had to do was to refuse to come to an agreement about how to split the money. So what did these participants do? This time the majority of participants—

Why did this happen? When people make joint decisions, each feels diminished responsibility for it. Participants in the first condition were faced with a moral dilemma: Do I take the money, which I’m tempted to do, or save the mouse, which I suppose is the right thing to do? No matter what they decided, the decision was theirs. But participants in the second condition made their decision together, and thus probably found it easier to give in to temptation because they had someone else with whom to share the blame.

Altruism

Are human beings ever truly altruistic?

Cooperation solves the problem of scarce resources. But is that the only reason we cooperate with others? Aren’t we ever just…well, nice? Altruism is behavior that benefits another without benefiting oneself, and for centuries, scientists and philosophers have argued about whether people are ever truly altruistic. That might seem like an odd argument to have. After all, people give their blood to the injured, their food to the homeless, and their arms to the elderly. We volunteer, we tithe, we donate. People do nice things all the time! Isn’t that evidence of altruism?

Well, not exactly. Behaviors that appear to be altruistic often have hidden benefits for those who do them. Consider some simple examples in the realm of animal behavior. Birds and squirrels make alarm calls when they see a predator, which puts them at increased risk of being eaten but allows their fellow birds and squirrels to escape. Ants and bees spend their lives caring for the offspring of the queen rather than bearing offspring of their own. Although these behaviors appear to be altruistic, they actually aren’t because the helpers are genetically related to the helpees. The squirrels most likely to make alarm calls are those most closely related to the other squirrels in the den (Maynard-

517

©MARTY KATZ/WASHINGTONPHOTOGRAPHER.COM

The behavior of nonhuman animals provides little if any evidence of genuine altruism (cf. Bartal, Decety, & Mason, 2011). So what about us? Are we any different? Like other animals, we tend to help our kin more than strangers (Burnstein, Crandall, & Kitayama, 1994; Komter, 2010) and we tend to expect those we help to help us in return (Burger et al., 2009). But unlike other animals, we do sometimes provide benefits to complete strangers who have no chance of repaying us (Batson, 2002; Warneken & Tomasello, 2009). We hold the door for people who share precisely none of our genes and tip waiters in restaurants to which we will never return. And we do more than that. As the World Trade Center burned on the morning of September 11, 2001, civilians in sailboats headed toward the destruction rather than away from it, initiating the largest waterborne evacuation in U.S. history. As one observer remarked, “If you’re out on the water in a pleasure craft and you see those buildings on fire, in a strictly rational sense you should head to New Jersey. Instead, people went into potential danger and rescued strangers. That’s social” (Dreifus, 2003). Human beings can be truly altruistic, and some studies suggest that they are actually more altruistic than they realize (Miller & Ratner, 1998).

Reproduction: The Quest for Immortality

All animals must survive and reproduce. Social behavior is useful for survival, but it is an absolute prerequisite for reproduction, which doesn’t happen until people get very, very social. The first step on the road to reproduction is finding someone who wants to travel that road with us. How do we do that?

Selectivity

Why are women choosier than men?

DR. PAULZ AHL/PHOTO RESEARCHERS

With the exception of a few well-

518

One reason for this is biology. Men produce billions of sperm in their lifetimes, their ability to conceive a child tomorrow is not inhibited by having conceived one today, and conception has no significant physical costs. On the other hand, women produce a small number of eggs in their lifetimes, conception eliminates their ability to conceive for at least 9 more months, and pregnancy produces physical changes that increase their nutritional requirements and put them at risk of illness and death. Therefore, if a man mates with a woman who does do not produce healthy offspring or who won’t do her part to raise them, he’s lost nothing but 10 minutes and a teaspoon of bodily fluid. But if a woman makes the same mistake, she has lost a precious egg, borne the costs of pregnancy, risked her life in childbirth, and missed at least 9 months of other reproductive opportunities. Clearly, our basic biology makes sex a riskier proposition for women than for men.

But if basic biology pushes women to be choosier then men, culture and experience can push every bit as hard (Petersen & Hyde, 2010; Zentner, & Mitura, 2012). For example, women may be choosier than men simply because they are approached more often (Conley et al., 2011) or because the reputational costs of promiscuity are higher (Eagly & Wood, 1999; Kasser & Sharma, 1999). Indeed, when sex becomes expensive for men (e.g., when they are choosing a long-

Attraction

For most of us, there is a very small number of people with whom we are willing to have sex, an even smaller number of people with whom we are willing to have children, and a staggeringly large number of people with whom we are unwilling to have either. So when we meet someone new, how do we decide which of these categories they belong in? Many things go into choosing a date, a lover, or a partner for life, but perhaps none is more important than the simple feeling we call attraction (Berscheid & Reis, 1998). Research suggests that this feeling is caused by a range of factors that can be roughly divided into three kinds: the situational, the physical, and the psychological.

Situational Factors. One of the best predictors of any kind of interpersonal relationship is the physical proximity of the people involved (Nahemow & Lawton, 1975). In one study, students who had been randomly assigned to university housing almost a year earlier were asked to name their three closest friends, and nearly half named their next-

519

THE REAL WORLD: Making the Move

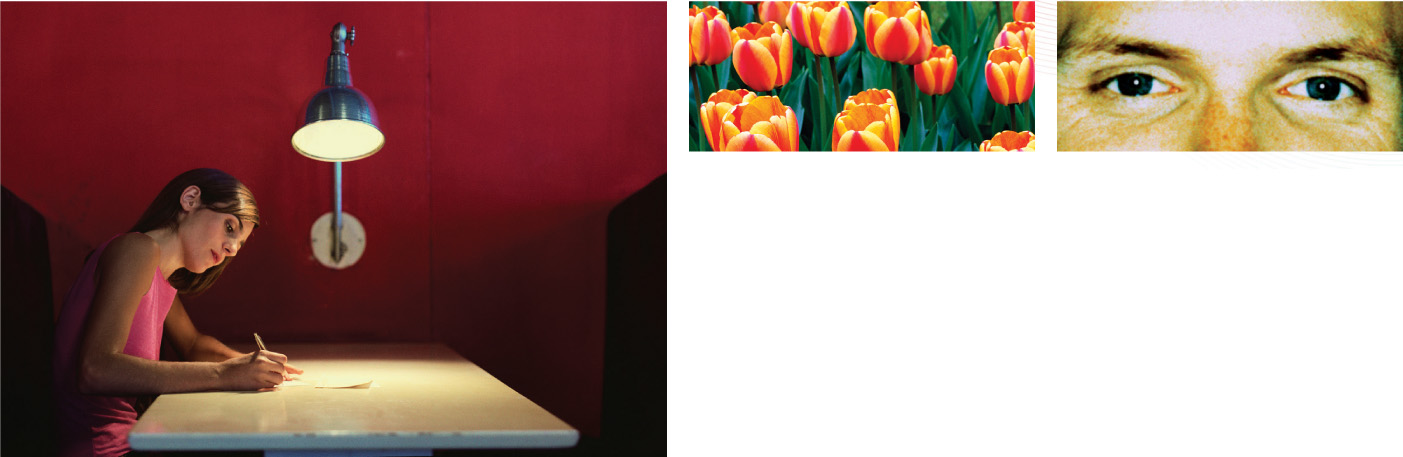

When it comes to selecting romantic partners, women tend to be choosier than men, and most scientists think that has a lot to do with differences in their reproductive biology. But psychologists Eli Finkel and Paul Eastwick (2009) thought that it might also have something to do with the nature of the courtship dance itself.

When it comes to approaching a potential romantic partner, the person with the most interest should be most inclined to “make the first move.” Of course, in most cultures, men are expected to make the first move. Could it be that making the first move causes men to think that they have more interest than women do and causes women to think they have less? In other words, could the rule about first moves be one of the reasons why women are choosier?

To find out, the researchers teamed up with a local speed dating service and created two kinds of speed dating events. In the traditional event, the women stayed in their seats and the men moved around the room, stopping to spend a few minutes chatting with each woman. In the nontraditional event, the men stayed in their seats and the women moved around the room, stopping to spend a few minutes chatting with each man. When the event was over, the researchers asked each man and woman privately to indicate whether they wanted to exchange phone numbers with any of the potential partners they’d met.

The results were striking (see the accompanying figure). When men made the move (as they traditionally do), women were the choosier gender. That is, men wanted to get a lot more phone numbers than women wanted to give. But when women made the move, men were the choosier gender, and women asked for more numbers than men were willing to hand over. Apparently, approaching someone makes us eager and being approached makes us cautious. One reason why women are so often the choosier gender may simply be that, in most cultures, men are expected to make the first move.

Why does proximity influence attraction?

Proximity provides something else as well. Every time we encounter a person, that person becomes a bit more familiar to us, and people generally prefer familiar to novel stimuli. The mere exposure effect is the tendency for liking to increase with the frequency of exposure (Bornstein, 1989; Zajonc, 1968). For instance, in some experiments, geometric shapes, faces, or alphabetical characters were flashed on a computer screen so quickly that participants were unaware of having seen them. Participants were then shown some of the “old” stimuli that had been flashed across the screen as well as some “new” stimuli that had not. Although they could not reliably say which stimuli were old and which were new, they did tend to like the old stimuli better than the new ones (Monahan, Murphy, & Zajonc, 2000). The fact that mere exposure leads to liking may explain why college students who were randomly assigned to seats during a brief psychology experiment were likely to be friends with the person they sat next to a full year later (Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2008). There are some circumstances under which “familiarity breeds contempt” (Norton, Frost, & Ariely, 2007), but for the most part familiarity seems to breed liking (Reis et al., 2011).

520

Attraction can be the result of geographical accidents that put people in the same place at the same time, but some places and times are clearly better than others. In one study, researchers observed men as they crossed a swaying suspension bridge. An attractive female researcher approached the men, either when they were in the middle of the bridge or after they had finished crossing it, and asked them to complete a survey. After they did so, she gave each man her telephone number and offered to explain her project in greater detail if he called. Results showed that the men were more likely to call the woman when they had met her in the middle of the swaying bridge (Dutton & Aron, 1974). Why? You may recall from the Emotion and Motivation chapter that people can misinterpret physiological arousal as a sign of attraction (Byrne et al., 1975; Schachter & Singer, 1962). The men were presumably more aroused when they were in the middle of a swaying bridge, and some of those men mistook their arousal for attraction.

Physical Factors. Once people are in the same place at the same time, they can begin to learn about each other’s personal qualities, and in most cases, the first quality they learn about is the other person’s appearance. You probably knew that appearance influences attraction, but this influence may be stronger than you thought. In one study, researchers arranged a dance for first-

AP PHOTO/MARY ALTAFFER

Why is physical appearance so important?

521

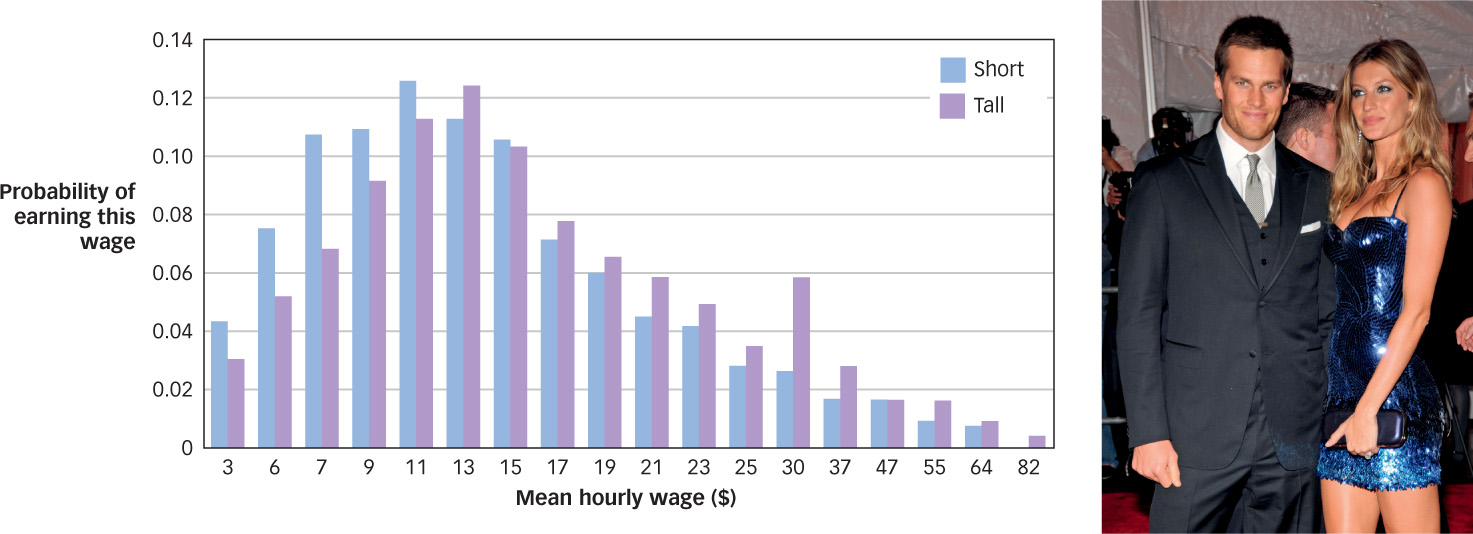

Beauty gets us more than dates (Etcoff, 1999; Langlois et al., 2000). Beautiful people have more sex, more friends, and more fun than the rest of us do (Curran & Lippold, 1975), and they even earn about 10% more money over the course of their lives (Hamermesh & Biddle, 1994; see FIGURE 13.6). We tend to think that beautiful people also have superior personal qualities (Dion, Berscheid, & Walster, 1972; Eagly et al., 1991), and in some cases they do. For instance, because beautiful people have more friends and more opportunities for social interaction, they tend to have better social skills than less beautiful people (Feingold, 1992b). Appearance is so powerful that it even influences how mothers treat their own children: Mothers are more affectionate and playful when their children are attractive than unattractive (Langlois et al., 1995). Indeed, the only real disadvantage of being beautiful is that it can sometimes cause others to feel threatened (Agthe, Spörrle, & Maner, 2010). It is interesting to note that men and women are equally influenced by the appearance of their potential partners (Eastwick et al., 2011), but men are more willing to admit it (Feingold, 1990).

Figure 13.6: Height Matters NFL quarterback Tom Brady is 6′4″ and his wife, supermodel Gisele Bunchen, is 5′10″. Research shows that tall people earn $789 more per inch per year. The graph shows the average hourly wage of adult White men in the United States classified by height (Mankiw & Weinzierl, 2010).

Figure 13.6: Height Matters NFL quarterback Tom Brady is 6′4″ and his wife, supermodel Gisele Bunchen, is 5′10″. Research shows that tall people earn $789 more per inch per year. The graph shows the average hourly wage of adult White men in the United States classified by height (Mankiw & Weinzierl, 2010).

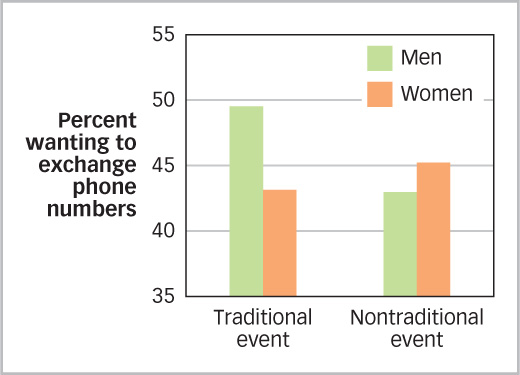

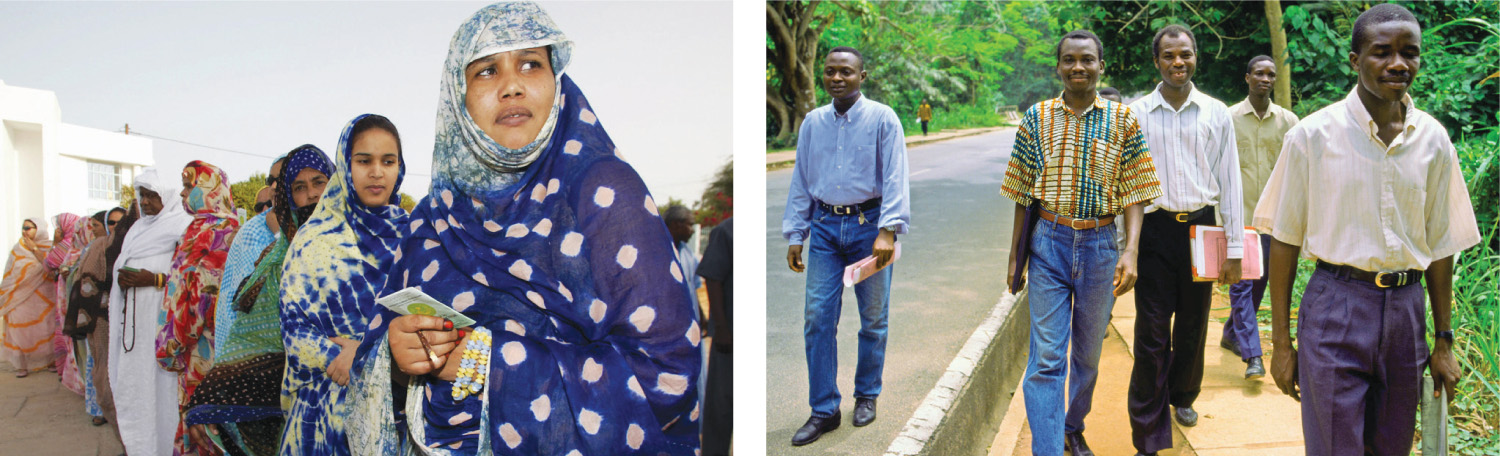

So yes, it pays to be beautiful. But what exactly constitutes beauty? The answer to that question varies across cultures. In the United States, for example, most women want to be slender, but in Mauritania, young girls are forced to drink up to 5 gallons of high-

Beauty may vary across cultures, but it is not entirely in the eye of the beholder. Different cultures have different standards of beauty, but those standards have a lot in common (Cunningham et al., 1995). For example, people in all cultures seem to have similar preferences about the ideal body, face, and age of their romantic partners.

Body shape. Male bodies are considered most attractive when they approximate an inverted triangle (i.e., broad shoulders with a narrow waist and hips), and female bodies are considered most attractive when they approximate an hourglass (i.e., broad shoulders and hips with a narrow waist). In fact, the most attractive female body across many cultures seems to be the “perfect hourglass” in which the waist is precisely 70% the size of the hips (Singh, 1993). Culture may determine whether men prefer women who are heavy or thin, but in all cultures men seem to prefer this particular waist-

Body shape. Male bodies are considered most attractive when they approximate an inverted triangle (i.e., broad shoulders with a narrow waist and hips), and female bodies are considered most attractive when they approximate an hourglass (i.e., broad shoulders and hips with a narrow waist). In fact, the most attractive female body across many cultures seems to be the “perfect hourglass” in which the waist is precisely 70% the size of the hips (Singh, 1993). Culture may determine whether men prefer women who are heavy or thin, but in all cultures men seem to prefer this particular waist-to- hip ratio.  Standards of beauty can vary across cultures. Mauritanian women long to be obese (left). Ghanian men are grateful to be short (right).SEYLLOU/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Standards of beauty can vary across cultures. Mauritanian women long to be obese (left). Ghanian men are grateful to be short (right).SEYLLOU/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

DWYER/ALAMY Symmetry. People in all cultures seem to prefer faces and bodies that are bilaterally symmetrical—that is, faces and bodies whose left half is a mirror image of the right half (Perilloux, Webster, & Gaulin, 2010; Perrett et al., 1999).

Symmetry. People in all cultures seem to prefer faces and bodies that are bilaterally symmetrical—that is, faces and bodies whose left half is a mirror image of the right half (Perilloux, Webster, & Gaulin, 2010; Perrett et al., 1999). Age. Characteristics such as large eyes, high eyebrows, and a small chin make people look immature or “baby-

Age. Characteristics such as large eyes, high eyebrows, and a small chin make people look immature or “baby-faced” (Berry & McArthur, 1985). As a general rule, female faces are considered more attractive when they have immature features, and male faces are considered more attractive when they have mature features (Cunningham, Barbee, & Pike, 1990; Zebrowitz & Montepare, 1992). Women prefer older men and men prefer younger women in every human culture ever studied (Buss, 1989).

What kind of information does physical appearance convey?

But why? Is there any rhyme or reason to this list of scenic attractions? Some psychologists think so. They suggest that nature has designed us to be attracted to people who (a) have good genes and (b) will be good parents (Gallup & Frederick, 2010; Neuberg, Kenrick, & Schaller, 2010). The features we all find attractive happen to be reliable indicators of these things. For example:

Body shape. Testosterone causes male bodies to become “inverted triangles” just as estrogen causes female bodies to become “hourglasses.” Men who are high in testosterone tend to be socially dominant and therefore have more resources to devote to their offspring, whereas women who are high in estrogen tend to be especially fertile and potentially have more offspring to make use of those resources. In other words, body shape is an indicator of male dominance and female fertility. In fact, women who have the perfect hourglass figure do tend to bear healthier children than do women with other waist-

Body shape. Testosterone causes male bodies to become “inverted triangles” just as estrogen causes female bodies to become “hourglasses.” Men who are high in testosterone tend to be socially dominant and therefore have more resources to devote to their offspring, whereas women who are high in estrogen tend to be especially fertile and potentially have more offspring to make use of those resources. In other words, body shape is an indicator of male dominance and female fertility. In fact, women who have the perfect hourglass figure do tend to bear healthier children than do women with other waist-to- hip ratios (Singh, 1993).  Symmetry. Symmetry is a sign of genetic health (Jones et al., 2001; Thornhill & Gangestad, 1993), which may explain why people are so good at detecting it. Indeed, women can distinguish between symmetrical and asymmetrical men by smell, and their preference for symmetrical men is especially pronounced when they are ovulating (Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999).

Symmetry. Symmetry is a sign of genetic health (Jones et al., 2001; Thornhill & Gangestad, 1993), which may explain why people are so good at detecting it. Indeed, women can distinguish between symmetrical and asymmetrical men by smell, and their preference for symmetrical men is especially pronounced when they are ovulating (Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999). Age. Younger women are generally more fertile than older women, whereas older men generally have more resources than younger men. Thus, a youthful appearance is a signal of a woman’s ability to bear children, just as a mature appearance is a signal of a man’s ability to raise them.

Age. Younger women are generally more fertile than older women, whereas older men generally have more resources than younger men. Thus, a youthful appearance is a signal of a woman’s ability to bear children, just as a mature appearance is a signal of a man’s ability to raise them.

523

If the feeling we call attraction is simply nature’s way of telling us that we are in the presence of a person who has good genes and a propensity to be a good parent, then it isn’t any wonder that people in different cultures appreciate so many of the same features in the opposite sex. Of course, appreciation is one thing and action is another, and studies show that while everyone may desire the most beautiful person in the room, most people tend to approach, date, and marry someone who is about as attractive as they are (Berscheid et al., 1971; Lee et al., 2008).

Why is similarity such a powerful determinant of attraction?

Psychological Factors. If attraction is all about big biceps and high cheekbones, then why don’t we just skip the small talk and pick our mates from photographs? Because for human beings, attraction is about much more than that. Physical appearance is assessed easily and early (Lenton & Francesconi, 2010), and it determines who draws our attention and quickens our pulse. But once people begin interacting they quickly move beyond appearances (Cramer, Schaefer, & Reid, 1996; Regan, 1998). People’s inner qualities—

How much wit and wisdom do we want our mate to have? Research suggests that people are most attracted to those who are similar (Byrne, Ervin, & Lamberth, 1970; Byrne & Nelson, 1965; Hatfield & Rapson, 1992; Neimeyer & Mitchell, 1988). We marry people with similar levels of education, religious backgrounds, ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses, and personalities (Botwin, Buss, & Shackelford, 1997; Buss, 1985; Caspi & Herbener, 1990). We’re even attracted to those who use pronouns the same way we do (Ireland et al., 2010). In fact, of all the variables psychologists have ever studied, gender appears to be the only one for which the majority of people have a consistent preference for dissimilarity.

Why is similarity so attractive? First, it’s easy to interact with people who are similar to us because we can instantly agree on a wide range of issues, such as what to eat, where to live, how to raise children, and how to spend our money. Second, when someone shares our attitudes and beliefs, we feel more confident that those attitudes and beliefs are correct (Byrne & Clore, 1970). Indeed, research shows that when a person’s attitudes or beliefs are challenged, they become even more attracted to similar others (Greenberg et al., 1990; Hirschberger, Florian, & Mikulincer, 2002). Third, if we like people who share our attitudes and beliefs, then we can reasonably expect them to like us for the same reason, and being liked is a powerful source of attraction (Aronson & Worchel, 1966; Backman & Secord, 1959; Condon & Crano, 1988). Although we tend to like people who like us, it is worth noting that we especially like people who like us and who don’t like anyone else (Eastwick et al., 2007).

524

Our desire for similarity goes beyond attitudes and beliefs and extends to abilities as well. For example, we may admire extraordinary skill in athletes and actors, but when it comes to friends and lovers, extraordinary people can threaten our self-

Relationships

LIGHTSCAPES PHOTOGRAPHY, INC./CORBIS

Why do people form long-

Once we have selected and attracted a mate, we are ready to reproduce. (Note: It is perfectly fine to pause for dinner.) Human reproduction ordinarily happens in the context of committed, long-

One answer is that we’re born half-

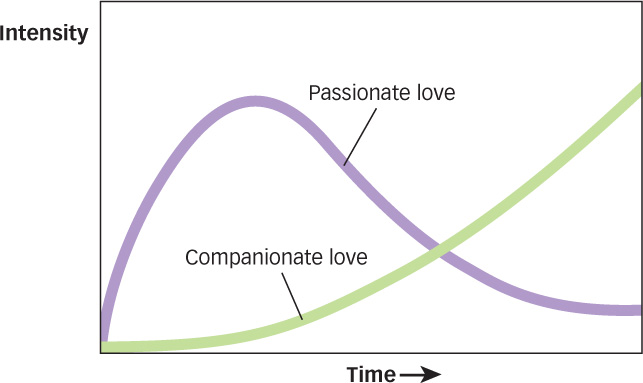

Figure 13.7: Passionate and Companionate Love Companionate and passionate love have different time courses and trajectories. Passionate love begins to cool within just a few months, but companionate love can grow slowly but steadily over years.

Figure 13.7: Passionate and Companionate Love Companionate and passionate love have different time courses and trajectories. Passionate love begins to cool within just a few months, but companionate love can grow slowly but steadily over years.

Love and Marriage. In most cultures, committed, long-

But what exactly is love? Psychologists distinguish between two basic kinds: passionate love, which is an experience involving feelings of euphoria, intimacy, and intense sexual attraction, and companionate love, which is an experience involving affection, trust, and concern for a partner’s well-

525

Divorce: When the Costs Outweigh the Benefits

How do people weigh the costs and benefits of their relationships?

The most recent U.S. government census statistics indicate that for every two couples who get married, one couple gets divorced. But why? Although feelings of love, happiness, and satisfaction may lead us to marriage, the lack of those feelings doesn’t seem to lead us to divorce. Marital satisfaction is only weakly correlated with marital stability (Karney & Bradbury, 1995), suggesting that relationships break up or remain intact for reasons other than the satisfaction of those involved (Drigotas & Rusbult, 1992; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Relationships offer both benefits (love, sex, and financial security) and costs (responsibility, conflict, loss of freedom). Social exchange is the hypothesis that people remain in relationships only as long as they perceive a favorable ratio of costs to benefits (Homans, 1961; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). For example, a relationship that provides an acceptable level of benefits at a reasonable cost will probably be maintained, and one that doesn’t won’t. Research suggests that this hypothesis is generally true, but there are three important caveats:

The acceptableness of any cost–benefit ratio depends on the alternatives. A person’s comparison level refers to the cost-

The acceptableness of any cost–benefit ratio depends on the alternatives. A person’s comparison level refers to the cost-benefit ratio that people believe they deserve or could attain in another relationship (Rusbult et al., 1991; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). A cost–benefit ratio that is acceptable to two people who are stranded on a desert island might not be acceptable to the same two people if they were living in a large city where each had access to other potential partners. A cost–benefit ratio is acceptable when we feel that it is the best we can or should do. People may want their cost–benefit ratios to be high, but they also want them to be roughly the same as their partner’s. Studies show that people care about equity, which is a state of affairs in which the cost–benefit ratios of two partners are roughly equal (Bolton & Ockenfels, 2000; Messick & Cook, 1983; Walster, Walster, & Berscheid, 1978). For example, spouses are more distressed when their respective cost–benefit ratios are different than when their cost–benefit ratios are unfavorable, and this is true even when their cost–benefit ratio is more favorable than their partner’s (Schafer & Keith, 1980). Indeed, people who give too much are sometimes disliked just as much as those who give too little (Parks & Stone, 2010).

People may want their cost–benefit ratios to be high, but they also want them to be roughly the same as their partner’s. Studies show that people care about equity, which is a state of affairs in which the cost–benefit ratios of two partners are roughly equal (Bolton & Ockenfels, 2000; Messick & Cook, 1983; Walster, Walster, & Berscheid, 1978). For example, spouses are more distressed when their respective cost–benefit ratios are different than when their cost–benefit ratios are unfavorable, and this is true even when their cost–benefit ratio is more favorable than their partner’s (Schafer & Keith, 1980). Indeed, people who give too much are sometimes disliked just as much as those who give too little (Parks & Stone, 2010). Relationships can be thought of as investments into which people pour resources such as time, money, and affection, and research suggests that once people have poured resources into a relationship, they are willing to settle for less favorable cost–benefit ratios (Kelley, 1983; Rusbult, 1983). This is one of the reasons why people are much more likely to end new marriages than old ones (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002; Cherlin, 1992).

Relationships can be thought of as investments into which people pour resources such as time, money, and affection, and research suggests that once people have poured resources into a relationship, they are willing to settle for less favorable cost–benefit ratios (Kelley, 1983; Rusbult, 1983). This is one of the reasons why people are much more likely to end new marriages than old ones (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002; Cherlin, 1992).

526

Survival and reproduction require scarce resources, and aggression and cooperation are two ways to get them.

Survival and reproduction require scarce resources, and aggression and cooperation are two ways to get them. Aggression often results from negative affect, which can be caused by almost anything—

Aggression often results from negative affect, which can be caused by almost anything—from being insulted to being hot. The likelihood that a person will aggress when they feel negative affect is determined both by biological factors (such as testosterone level) and cultural factors (such as geography).  Cooperation is beneficial but risky, and one strategy for reducing its risks is to form groups whose members are biased in favor of each other. Unfortunately, groups often decide and behave badly.

Cooperation is beneficial but risky, and one strategy for reducing its risks is to form groups whose members are biased in favor of each other. Unfortunately, groups often decide and behave badly. Although behaviors that appear to be altruistic often have hidden benefits for the person who does them, there is little doubt that human beings can behave altruistically.

Although behaviors that appear to be altruistic often have hidden benefits for the person who does them, there is little doubt that human beings can behave altruistically. Both biology and culture tend to make the costs of reproduction higher for women than for men, which is one reason why women tend to be choosier when selecting potential mates.

Both biology and culture tend to make the costs of reproduction higher for women than for men, which is one reason why women tend to be choosier when selecting potential mates. Attraction is determined by situational factors (such as proximity), physical factors (such as symmetry), and psychological factors (such as similarity).

Attraction is determined by situational factors (such as proximity), physical factors (such as symmetry), and psychological factors (such as similarity). Human reproduction usually occurs within the context of a long-

Human reproduction usually occurs within the context of a long-term relationship. People weigh the costs and benefits of their relationships and tend to dissolve them when they think they can or should do better, when they and their partners have very different cost–benefit ratios, or when they have little invested in the relationship.