13.3 Social Cognition: Understanding People

Frank Ocean is sexy and talented. Whether or not you agree with that sentence, it almost certainly activated your medial prefrontal cortex, which is an area of your brain that is activated when you think about the attributes of other people but not about the attributes of inanimate objects such as houses or tools (Mitchell, Heatherton, & Macrae, 2002). Although most of your brain shows diminished activity when you are at rest, this area remains active all the time (Buckner, Andrews-

Of the millions of objects you might encounter, other human beings are the single most important. Social cognition is the processes by which people come to understand others, and your brain is doing it all day long. Whether you know it or not, your brain is constantly making inferences about others people’s thoughts and feelings, beliefs and desires, abilities and aspirations, intentions, needs, and characters. It bases these inferences on two kinds of information: the categories to which people belong, and the things they do and say.

538

HOT SCIENCE: The Wedding Planner

The human brain has nearly tripled in size in just 2 million years. The social brain hypothesis (Shultz & Dunbar, 2010) suggests that this happened primarily so that people could manage the everyday complexities of living in large social groups. What are those complexities?

Well, just think of what you’d need to know in order to seat people at a wedding. Does Uncle Jacob like Grandma Nora, does Grandma Nora hate Cousin Caleb, and if so, does Uncle Jacob hate Cousin Caleb too? With a guest list of just 150 people there are more than 10,000 of these dyadic relationships to consider—

In a recent study (Mason et al., 2010), researchers sought to answer this question by directly comparing people’s abilities to solve social and nonsocial problems. The nonsocial problem involved drawing inferences about metals. Participants were told that there were two basic groups of metals, and that metals in the same group “attracted” each other, whereas metals in different groups “repelled” each other. Then, over a series of trials, participants were told about the relationships between particular metals and were asked to draw inferences about the missing relationship. For example, participants were told that gold and tin were both repelled by platinum, and they were then asked to infer the relationship between gold and tin. (The correct answer is “They are attracted to each other.”)

The experimenters also gave participants a social version of this problem. Participants were told about two groups of people. People who were in the same group were said to be attracted to each other, whereas people who were in different groups were said to be repelled by each other. Then, over a series of trials, participants learned about the relationships between particular people—

Although the social and nonsocial tasks were logically identical, results showed that participants were considerably faster and more accurate when drawing inferences about people than about metals. When the researchers replicated the study inside an MRI machine, they discovered that both tasks activated brain areas known to play a role in deductive reasoning, but that only the social task activated brain regions known to play a role in understanding other minds.

It appears that our ability to think about people outshines our ability to think about most everything else, which is good news for the social brain hypothesis—

Stereotyping: Drawing Inferences from Categories

How are stereotypes useful?

You’ll recall from the Language and Thought chapter that categorization is the process by which people identify a stimulus as a member of a class of related stimuli. Once we have identified a novel stimulus as a member of a category (“That’s a textbook”), we can then use our knowledge of the category to make educated guesses about the properties of the novel stimulus (“It’s probably expensive”) and act accordingly (“I think I’ll download it illegally”).

What we do with textbooks we also do with people. No, not the illegal downloading part. The educated guessing part. Stereotyping is the process by which people draw inferences about others based on their knowledge of the categories to which others belong. The moment we categorize a person as an adult, a male, a baseball player, and a Russian, we can use our knowledge of those categories to make some educated guesses about him, for example, that he shaves his face but not his legs, that he understands the infield fly rule, and that he knows more about Vladimir Putin than we do. When we offer children candy instead of cigarettes or ask gas station attendants for directions instead of financial advice, we are making inferences about people whom we have never met before based solely on their category membership. As these examples suggest, stereotyping is a very helpful process (Allport, 1954). And yet, ever since the word was coined by the journalist Walter Lippmann in 1936, it has had a distasteful connotation. Why? Because stereotyping is a helpful process that can often produce harmful results, and it does so because stereotypes tend to have four properties: They are inaccurate, overused, self-

539

Stereotypes Can Be Inaccurate

Why might we have inaccurate beliefs about groups even after directly observing them?

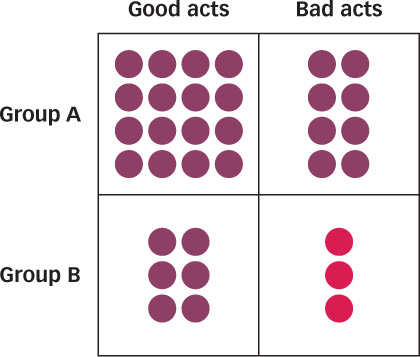

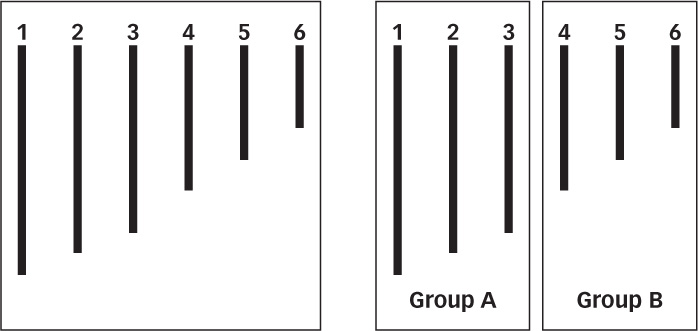

Figure 13.15: Seeing Correlations That Aren’t Really There Both Group A and Group B each perform two-

Figure 13.15: Seeing Correlations That Aren’t Really There Both Group A and Group B each perform two-The inferences we draw about individuals are only as accurate as our stereotypes about the categories to which they belong. Although there was no evidence to indicate that Jews were especially materialistic or that African Americans were especially lazy, American college students held such beliefs for most of the last century (Gilbert, 1951; Karlins, Coffman, & Walters, 1969; Katz & Braly, 1933). They weren’t born holding these beliefs, so how did they acquire them? There are only two ways to acquire a belief about anything: to see for yourself or to take somebody else’s word for it. In fact, most of what we know about the members of human categories is hearsay—

But even direct observation can produce inaccurate stereotypes. For example, research participants in one study were shown a long series of positive and negative behaviors and were told that each behavior had been performed by a member of one of two groups: Group A or Group B (see FIGURE 13.15). The behaviors were carefully arranged so that each group behaved negatively exactly one third of the time. However, there were more positive than negative behaviors in the series, and there were more members of Group A than of Group B. As such, negative behaviors were rarer than positive behaviors, and Group B members were rarer than Group A members. After seeing the behaviors, participants correctly reported that Group A had behaved negatively one third of the time. However, they incorrectly reported that Group B had behaved negatively more than half the time (Hamilton & Gifford, 1976).

Why did this happen? Bad behavior was rare and being a member of Group B was rare. Thus, participants were especially likely to notice when the two co-

Stereotypes Can Be Overused

Because all thumbtacks are pretty much alike, our stereotypes about thumbtacks (small, cheap, painful when chewed) are quite useful. We will rarely be mistaken if we generalize from one thumbtack to another. But human categories are so variable that our stereotypes may offer only the vaguest of clues about the individuals who populate those categories. You probably believe that men have greater upper body strength than women do, and this belief is right on average. But the upper body strength of individuals within each of these categories is so varied that you cannot easily predict how much weight a particular person can lift simply by knowing that person’s gender. The inherent variability of human categories makes stereotypes much less useful than they seem.

How does categorization warp perception?

540

Alas, we don’t always recognize this because the mere act of categorizing a stimulus tends to warp our perceptions of that category’s variability. For instance, participants in some studies were shown a series of lines of different lengths (see FIGURE 13.16; McGarty & Turner, 1992; Tajfel & Wilkes, 1963). For one group of participants, the longest lines were labeled Group A and the shortest lines were labeled Group B, as they are on the right side of Figure 13.16. For the second group of participants, the lines were shown without these category labels, as they are on the left side of Figure 13.16. Interestingly, those participants who saw the category labels overestimated the similarity of the lines that shared a label and underestimated the similarity of lines that did not.

Figure 13.16: How Categorization Warps Perception People who see the lines on the right tend to overestimate the similarity of lines 1 and 3 and underestimate the similarity of lines 3 and 4. Simply labeling lines 1–3 Group A and lines 4–6 Group B causes the lines within a group to seem more similar to each other than they really are, and the lines in different groups to seem more different from each other than they really are.

Figure 13.16: How Categorization Warps Perception People who see the lines on the right tend to overestimate the similarity of lines 1 and 3 and underestimate the similarity of lines 3 and 4. Simply labeling lines 1–3 Group A and lines 4–6 Group B causes the lines within a group to seem more similar to each other than they really are, and the lines in different groups to seem more different from each other than they really are.

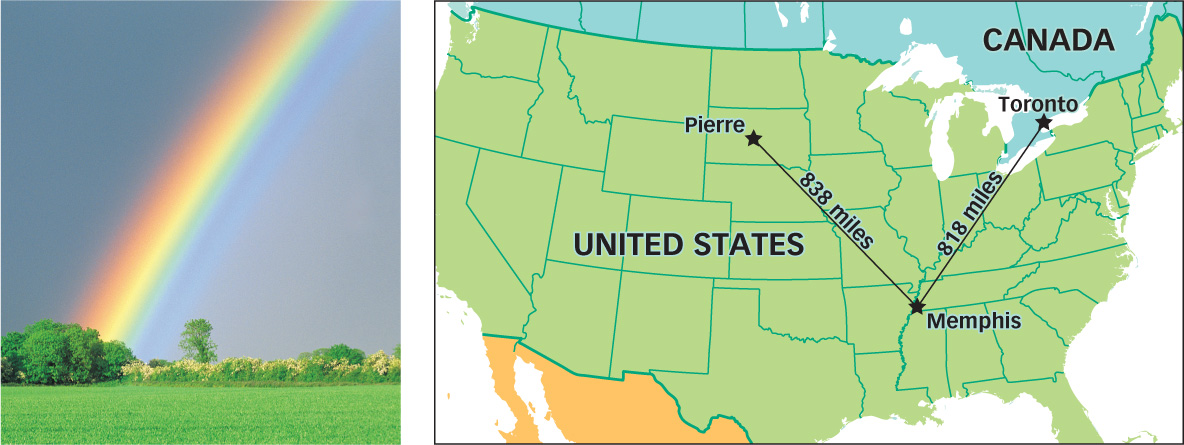

You’ve probably experienced this phenomenon yourself. For instance, we all identify colors as members of categories such as blue or green, and this leads us to overestimate the similarity of colors that share a category label and to underestimate the similarity of colors that do not. That’s why we see discrete bands of color when we look at rainbows, which are actually a smooth chromatic continuum (see FIGURE 13.17). When two cities are in the same country (Memphis and Pierre) people tend to underestimate their distance, but when two cities are in different countries (Memphis and Toronto) they tend to overestimate their distance (Burris & Branscombe, 2005). Indeed, people believe that they are more likely to feel an earthquake that happens 230 miles away when the earthquake happens in their state rather than a neighboring state (Mishra & Mishra, 2010).

Figure 13.17: Perceiving Categories Categorization can influence how we see colors and estimate distances.

Figure 13.17: Perceiving Categories Categorization can influence how we see colors and estimate distances.

What’s true of colors and cities is true of people as well. The mere act of categorizing people as Blacks or Whites, Jews or Gentiles, artists or accountants, can cause us to underestimate the variability within those categories (“All artists are wacky”) and to overestimate the variability between them (“Artists are much wackier than accountants”). When we underestimate the variability of a human category, we overestimate how useful our stereotypes can be (Park & Hastie, 1987; Rubin, & Badea, 2012).

541

Stereotypes Can Be Self-Perpetuating

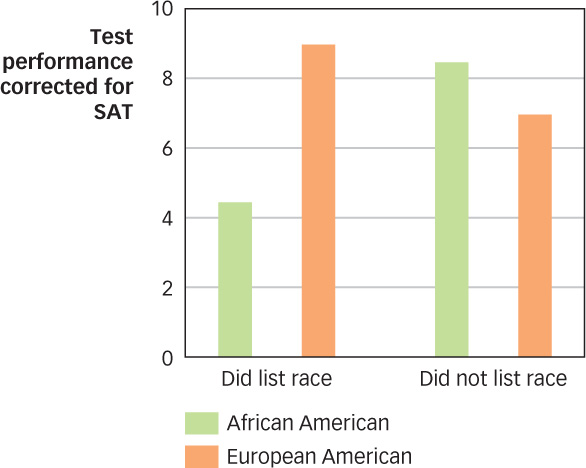

Figure 13.18: Stereotype Threat When asked to indicate their race before taking an exam, African American students performed below their academic level (as determined by their SAT scores).

Figure 13.18: Stereotype Threat When asked to indicate their race before taking an exam, African American students performed below their academic level (as determined by their SAT scores).

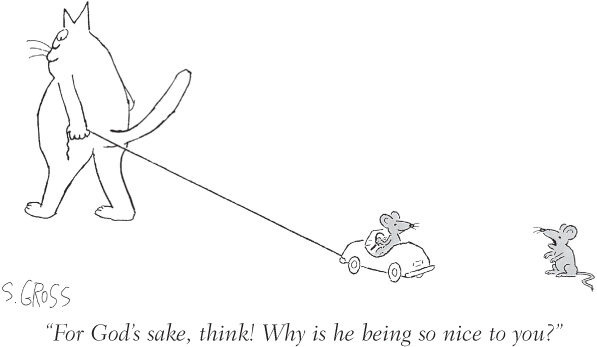

In what way is a stereotype like a virus?

When we meet a truck driver who likes ballet more than football or a senior citizen who likes Jay-

Self-fulfilling prophecy is the tendency for people to behave as they are expected to behave. When people know that observers have a negative stereotype about them, they may experience stereotype threat, which is the fear of confirming the negative beliefs that others may hold (Aronson & Steele, 2004; Schmader, Johns, & Forbes, 2008; Walton & Spencer, 2009). Ironically, this fear may cause them to behave in ways that confirm the very stereotype that threatened them. In one study (Steele & Aronson, 1995), African American and White students took a test, and half the students in each group were asked to list their race at the top of the exam. When students were not asked to list their races they performed at their academic level, but when students were asked to list their races, African American students became anxious about confirming a negative stereotype of their group, which caused them to perform well below their academic level (see FIGURE 13.18). Stereotypes perpetuate themselves in part by causing the stereotyped individual to behave in ways that confirm the stereotype.

Self-fulfilling prophecy is the tendency for people to behave as they are expected to behave. When people know that observers have a negative stereotype about them, they may experience stereotype threat, which is the fear of confirming the negative beliefs that others may hold (Aronson & Steele, 2004; Schmader, Johns, & Forbes, 2008; Walton & Spencer, 2009). Ironically, this fear may cause them to behave in ways that confirm the very stereotype that threatened them. In one study (Steele & Aronson, 1995), African American and White students took a test, and half the students in each group were asked to list their race at the top of the exam. When students were not asked to list their races they performed at their academic level, but when students were asked to list their races, African American students became anxious about confirming a negative stereotype of their group, which caused them to perform well below their academic level (see FIGURE 13.18). Stereotypes perpetuate themselves in part by causing the stereotyped individual to behave in ways that confirm the stereotype. Many of us think that nuns are traditional and proper. Does this photo of Sister Rosa Elena nailing Sister Amanda de Jesús with a snowball change your stereotype, or are you tempted to subtype them instead?BRIAN PLONKA/THE SPOKESMAN REVIEW

Many of us think that nuns are traditional and proper. Does this photo of Sister Rosa Elena nailing Sister Amanda de Jesús with a snowball change your stereotype, or are you tempted to subtype them instead?BRIAN PLONKA/THE SPOKESMAN REVIEW Even when people do not confirm stereotypes, observers often think they have. Perceptual confirmation is the tendency for people to see what they expect to see and this tendency helps perpetuate stereotypes. In one study, participants listened to a radio broadcast of a college basketball game and were asked to evaluate the performance of one of the players. Although all participants heard the same prerecorded game, some were led to believe that the player was African American and others were led to believe that the player was White. Participants’ stereotypes led them to expect different performances from athletes of different ethnic origins—

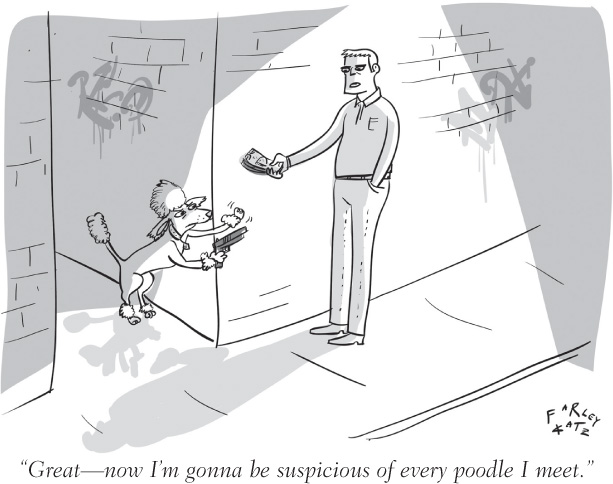

Even when people do not confirm stereotypes, observers often think they have. Perceptual confirmation is the tendency for people to see what they expect to see and this tendency helps perpetuate stereotypes. In one study, participants listened to a radio broadcast of a college basketball game and were asked to evaluate the performance of one of the players. Although all participants heard the same prerecorded game, some were led to believe that the player was African American and others were led to believe that the player was White. Participants’ stereotypes led them to expect different performances from athletes of different ethnic origins—and the participants perceived just what they expected. Those who believed the player was African American thought he had demonstrated greater athletic ability but less intelligence than did those who thought he was White (Stone, Perry, & Darley, 1997). Stereotypes perpetuate themselves in part by biasing our perception of individuals, leading us to believe that those individuals have confirmed our stereotypes even when they have not (Fiske, 1998).  So what happens when people clearly disconfirm our stereotypes? Subtyping is the tendency for people who receive disconfirming evidence to modify their stereotypes rather than abandon them (Weber & Crocker, 1983). For example, most of us think of people who work in public relations as sociable. In one study, participants learned about a PR agent who was slightly unsociable, and the results showed that their stereotypes about PR agents shifted a bit to accommodate this new information. So far, so good. But when participants learned about a PR agent who was extremely unsociable, their stereotypes did not change at all (Kunda & Oleson, 1997). Instead, they decided that extremely unsociable PR agent was “an exception to the rule” which allowed them to keep their stereotypes intact. Subtyping is a powerful method for preserving our stereotypes in the face of contradictory evidence.

So what happens when people clearly disconfirm our stereotypes? Subtyping is the tendency for people who receive disconfirming evidence to modify their stereotypes rather than abandon them (Weber & Crocker, 1983). For example, most of us think of people who work in public relations as sociable. In one study, participants learned about a PR agent who was slightly unsociable, and the results showed that their stereotypes about PR agents shifted a bit to accommodate this new information. So far, so good. But when participants learned about a PR agent who was extremely unsociable, their stereotypes did not change at all (Kunda & Oleson, 1997). Instead, they decided that extremely unsociable PR agent was “an exception to the rule” which allowed them to keep their stereotypes intact. Subtyping is a powerful method for preserving our stereotypes in the face of contradictory evidence.

542

Stereotyping Can Be Automatic

©RADIUS IMAGES/ALAMY

Can we decide not to stereotype?

If we recognize that stereotypes are inaccurate and self-

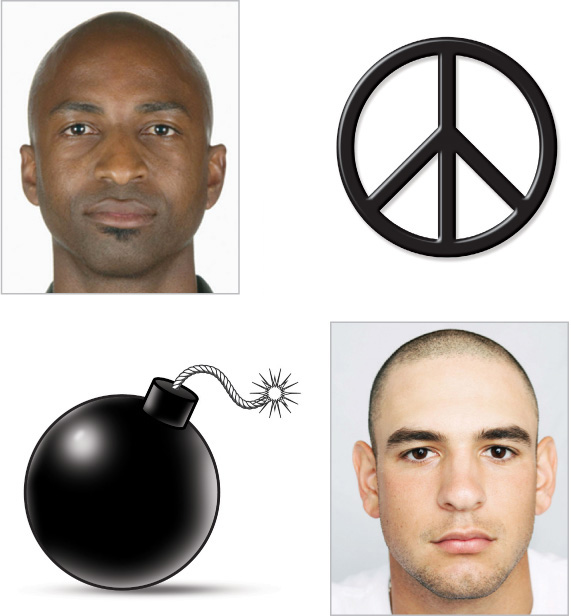

For example, in one study, participants played a video game in which photos of Black or White men holding either guns or cameras were flashed on the screen for less than 1 second each. Participants earned money by shooting men with guns and lost money by shooting men with cameras. The results showed that participants made two kinds of mistakes: They tended to shoot Black men holding cameras and tended not to shoot White men holding guns (Correll et al., 2002). Although the photos appeared on the screen so quickly that participants did not have enough time to consciously consider their stereotypes, those stereotypes worked unconsciously, causing them to mistake a camera for a gun when it was in the hands of a Black man and a gun for a camera when it was in the hands of a White man. Sadly, Black participants were just as likely to make this pattern of errors as were White participants. Why did this happen?

Stereotypes comprise all the information about human categories that we have absorbed over the years from friends and uncles, books and blogs, jokes and movies and late-

In fact, some research suggests that trying not to use our stereotypes can make matters worse instead of better. Participants in one study were shown a photograph of a tough-

Although stereotyping is unconscious and automatic, it is not inevitable (Blair, 2002; Kawakami et al., 2000; Milne & Grafman, 2001; Rudman, Ashmore, & Gary, 2001). For instance, police officers who receive special training before playing the camera or gun video game described earlier do not show the same biases that ordinary people do (Correll et al., 2007). Like ordinary people, they take a few milliseconds longer to decide not to shoot a Black man than a White man, indicating that their stereotypes are unconsciously and automatically influencing their thinking. But unlike ordinary people, they don’t actually shoot Black men more often than White men, indicating that they have learned how to keep those stereotypes from influencing their behavior. Other studies show that even simple games and exercises can reduce the automatic influence of stereotypes (Phills et al., 2011; Todd et al., 2011).

543

Attribution: Drawing Inferences from Actions

When does a person’s behavior tell us something about them?

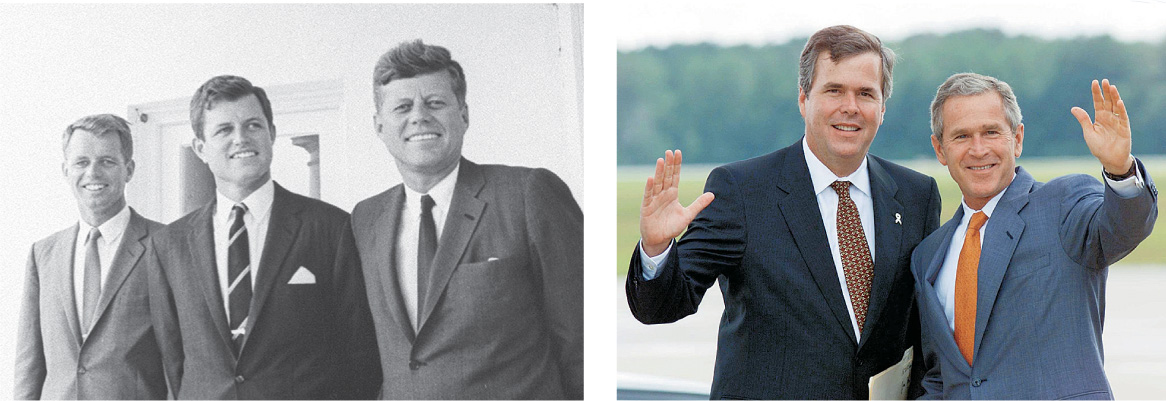

In 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave a speech in which he described his vision for America: “I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Research on stereotyping demonstrates that Dr. King’s concerns are still well justified. We do indeed judge others by the color of their skin—

Not necessarily. Treating a person as an individual means judging them by their own words and deeds. This is more difficult than it sounds because the relationship between what a person is and what a person says or does is not always straightforward. An honest person may lie to save a friend from embarrassment, and a dishonest person may tell the truth to bolster her credibility. Happy people have some weepy moments, polite people can be rude in traffic, and people who despise us can be flattering when they need a favor. In short, people’s behavior sometimes tells us about the kinds of people they are, but sometimes it simply tells us about the kinds of situations they happen to be in.

To understand people, we need to know not only what they did but also why they did it. Is the batter who hit the home run a talented slugger, or was the wind blowing in just the right direction at just the right time? Is the politician who gave the pro-

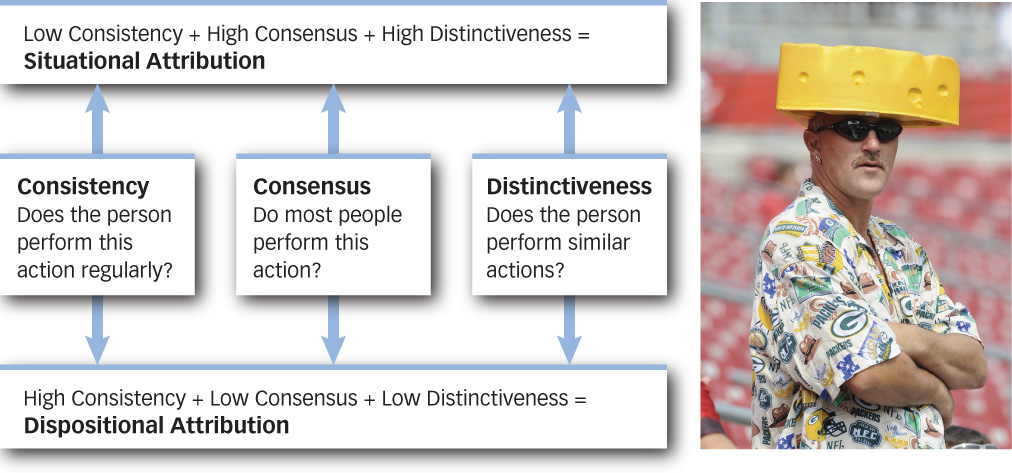

How do we know whether to make a dispositional or a situational attribution? According to the covariation model (Kelley, 1967), we must consider the consistency, consensuality, and distinctiveness of the action. For example, why is the man in photo FIGURE 13.19 wearing a cheese-

Figure 13.19: The Covariation Model of Attribution The covariation model tells us whether to make a dispositional or situational attribution for a person’s action.

Figure 13.19: The Covariation Model of Attribution The covariation model tells us whether to make a dispositional or situational attribution for a person’s action.

Why do we tend to make dispositional attributions?

544

As sensible as this seems, research suggests that people don’t always use this information as they should. The correspondence bias is the tendency to make a dispositional attribution when we should instead make a situational attribution (Gilbert & Malone, 1995; Jones & Harris, 1967; Ross, 1977). This bias is so common and so basic that it is often called the fundamental attribution error. For example, volunteers in one experiment played a trivia game in which one participant acted as the quizmaster and made up a list of unusual questions, another participant acted as the contestant and tried to answer those questions, and a third participant acted as the observer and simply watched the game. The quizmasters tended to ask tricky questions based on their own idiosyncratic knowledge, and contestants were generally unable to answer them. After watching the game, the observers were asked to decide how knowledgeable the quiz-

What causes the correspondence bias? First, the situational causes of behavior are often invisible (Ichheiser, 1949). For example, professors tend to assume that fawning students really do admire them in spite of the strong incentive for students to kiss up to those who control their grades. The problem is that professors can literally see students laughing at witless jokes and applauding after boring lectures, but they cannot see “control over grades.” Situations are not as tangible or visible as behaviors, so it is all too easy to ignore them (Taylor & Fiske, 1978). Second, situational attributions tend to be more complex than dispositional attributions and require more time and attention. When participants in one study were asked to make attributions while performing a mentally taxing task (namely, keeping a seven-

545

AP PHOTO/DOUG MILLS

The correspondence bias is stronger in some cultures than others (Choi, Nisbett, & Norenzayan, 1999), among some people than others (D’Agostino & Fincher-

People make inferences about others based on the categories to which they belong (stereotyping). This method can lead them to misjudge others because stereotypes can be inaccurate, overused, self-

People make inferences about others based on the categories to which they belong (stereotyping). This method can lead them to misjudge others because stereotypes can be inaccurate, overused, self-perpetuating, unconscious, and automatic.  People make inferences about others based on their behaviors. This method can lead them to misjudge others because people tend to attribute actions to dispositions even when they should attribute them to situations.

People make inferences about others based on their behaviors. This method can lead them to misjudge others because people tend to attribute actions to dispositions even when they should attribute them to situations.

546