14.2 Stress Reactions: All Shook Up

It was a regular Tuesday morning in New York City. College students were sitting in their morning classes. People were arriving at work and the streets were beginning to fill with shoppers and tourists. Then, at 8:46 a.m., American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center. People watched in horror. How could this have happened? This seemed like a terrible accident. Then at 9:03 a.m., United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center. There were then reports of a plane crashing into the Pentagon. And another somewhere in Pennsylvania. America was under attack, and no one knew what would happen next on this terrifying morning of September 11, 2001. The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center were an enormous stressor that had a lasting impact on many people, physically and psychologically. People living in close proximity to the World Trade Center (within 1.5 miles) during 9/11 were found to have less gray matter in the amygdala, hippocampus, insula, anterior cingulate, and medial prefrontal cortex relative to those living more than 200 miles away during the attacks, suggesting that the stress associated with the attacks may have reduced the size of these parts of the brain that play an important role in emotion, memory, and decision making (Ganzel et al., 2008). Children who watched more television coverage of 9/11 had higher symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder than children who watched less coverage (Otto et al., 2007). People around the country who had a stronger acute stress response to the events of 9/11 had a 53% increased incidence of heart problems over the next 3 years (Holman et al., 2008). Stress can produce changes in every system of the body and mind, stimulating both physical reactions and psychological reactions. Let’s consider each in turn.

554

Physical Reactions

Walter Cannon (1929) coined a phrase to describe the body’s response to any threatening stimulus: the fight-or-flight response, an emotional and physiological reaction to an emergency that increases readiness for action. The mind asks, “Should I stay and battle this somehow, or should I run like mad?” And the body prepares to react. If you’re a cat at this time, your hair stands on end. If you’re a human, your hair stands on end, too, but not as visibly. Cannon recognized this common response across species and suspected that it might be the body’s first mobilization to any threat.

How does the body react to a fight-

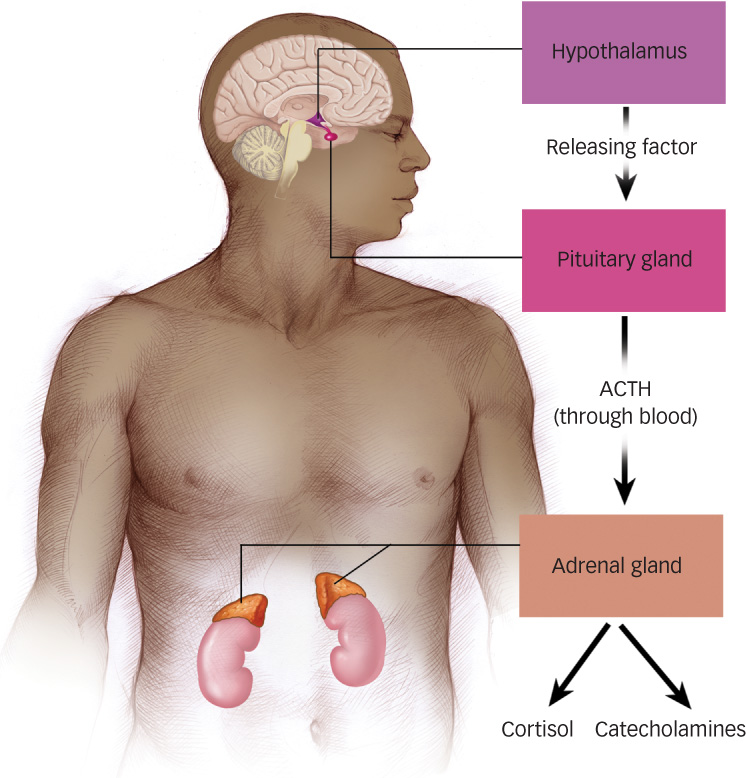

Research conducted since Cannon’s discovery has revealed what is happening in the brain and body during this reaction. Brain activation in response to threat occurs in the hypothalamus, stimulating the nearby pituitary gland, which in turn releases a hormone known as ACTH (short for adrenocorticotropic hormone). ACTH travels through the bloodstream and stimulates the adrenal glands atop the kidneys (see FIGURE 14.1). In this cascading response of the HPA (hypothalamic– pituitary– adrenocortical) axis, the adrenal glands are stimulated to release hormones, including the catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine), which increase sympathetic nervous system activation (and therefore increase heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration rate) and decrease parasympathetic activation (see the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter). The increased respiration and blood pressure make more oxygen available to the muscles to energize attack or to initiate escape. The adrenal glands also release cortisol, a hormone that increases the concentration of glucose in the blood to make fuel available to the muscles. Everything is prepared for a full-

Figure 14.1: HPA Axis Just a few seconds after a fearful stimulus is perceived, the hypothalamus activates the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). The ACTH then travels through the bloodstream to activate the adrenal glands to release catecholamines and cortisol, which energize the fight-

Figure 14.1: HPA Axis Just a few seconds after a fearful stimulus is perceived, the hypothalamus activates the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). The ACTH then travels through the bloodstream to activate the adrenal glands to release catecholamines and cortisol, which energize the fight-General Adaptation Syndrome

What might have happened if the terrorist attacks of 9/11 were spaced out over a period of days or weeks? Starting in the 1930s, Hans Selye, a Canadian physician, undertook a variety of experiments that looked at the physiological consequences of severe threats to well-

555

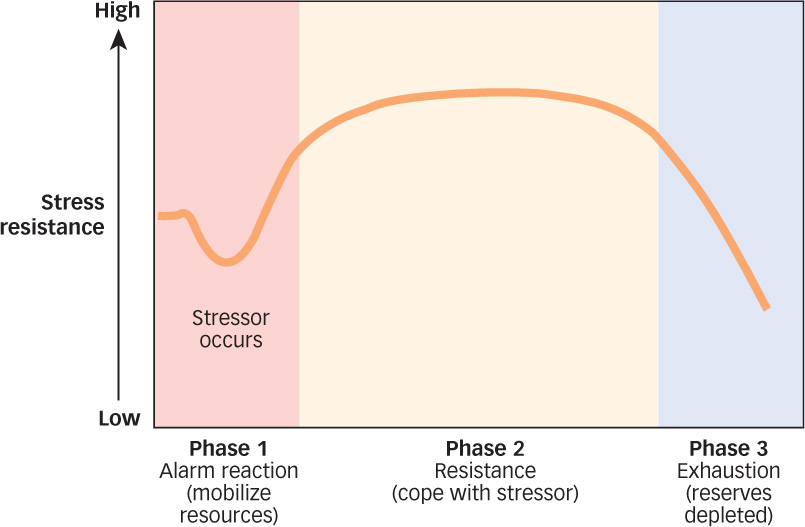

None of this is very good news. Although Friedrich Nietzsche once said, “What does not kill me makes me stronger,” Selye found that severe stress takes a toll on the body. He saw the GAS as occurring in three phases (see FIGURE 14.2):

Figure 14.2: Selye’s Three Phases of Stress Response In Selye’s theory, resistance to stress builds over time, but then can only last so long before exhaustion sets in.

Figure 14.2: Selye’s Three Phases of Stress Response In Selye’s theory, resistance to stress builds over time, but then can only last so long before exhaustion sets in.

What are the three phases of GAS?

First comes the alarm phase, in which the body rapidly mobilizes its resources to respond to the threat. Energy is required, and the body calls on its stored fat and muscle. The alarm phase is equivalent to Cannon’s fight-

First comes the alarm phase, in which the body rapidly mobilizes its resources to respond to the threat. Energy is required, and the body calls on its stored fat and muscle. The alarm phase is equivalent to Cannon’s fight-or- flight response.  Next, in the resistance phase, the body adapts to its high state of arousal as it tries to cope with the stressor. Continuing to draw on resources of fat and muscle, it shuts down unnecessary processes: digestion, growth, and sex drive stall; menstruation stops; production of testosterone and sperm decreases. The body is being taxed to generate resistance, and all the fun stuff is put on hold.

Next, in the resistance phase, the body adapts to its high state of arousal as it tries to cope with the stressor. Continuing to draw on resources of fat and muscle, it shuts down unnecessary processes: digestion, growth, and sex drive stall; menstruation stops; production of testosterone and sperm decreases. The body is being taxed to generate resistance, and all the fun stuff is put on hold. If the GAS continues long enough, the exhaustion phase sets in. The body’s resistance collapses. Many of the resistance-

If the GAS continues long enough, the exhaustion phase sets in. The body’s resistance collapses. Many of the resistance-phase defenses create gradual damage as they operate, leading to costs for the body that can include susceptibility to infection, tumor growth, aging, irreversible organ damage, or death.

Stress Effects on Health and Aging

RICHARD ELLIS/ALAMY

AP PHOTO/DOUGMILLS

AP PHOTO/PAUL SANCYA

AP PHOTO/ELISE AMENDOLA

AP PHOTO/CAROLYN KASTER

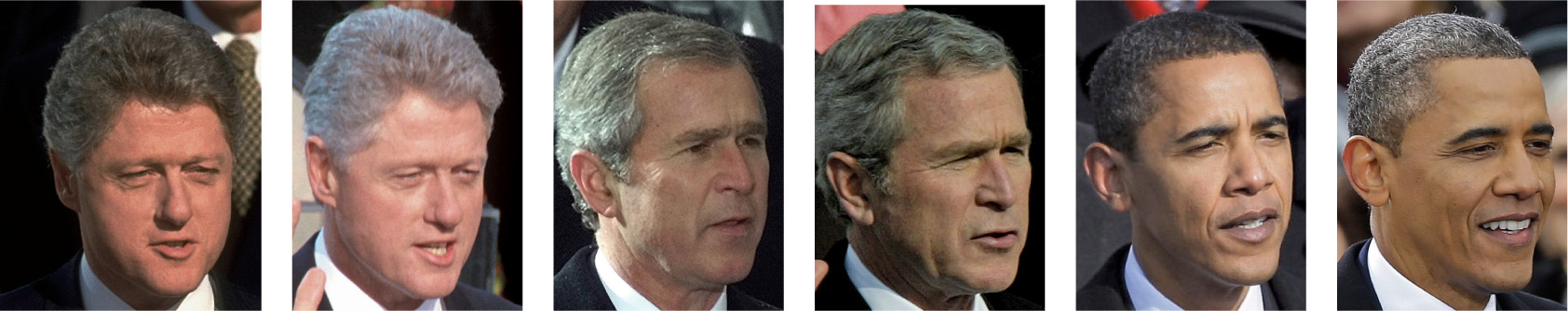

Right now, you are (we hope!) enjoying years of healthy living. Unfortunately, as people age, the body slowly begins to break down (just ask any of the authors of this book). Interestingly, recent research has revealed that stress significantly accelerates the aging process. Elizabeth Smart’s parents noted that, upon being reunited with her after 9 months of separation, they almost did not recognize her because she appeared to have aged so much (Smart, Smart, & Morton, 2003). Theirs is an extreme example; you can see examples of the effects of stress on aging around you in everyday life. People exposed to chronic stress, whether due to their relationships, job, or something else, experience actual wear and tear on their bodies and increased aging. Take a look at the pictures of the past three presidents before and after their terms as president of the United States (arguably, one of the most stressful jobs in the world). As you can see, they appear to have aged much more than the 4-

556

What is telomerase and what does it do for us?

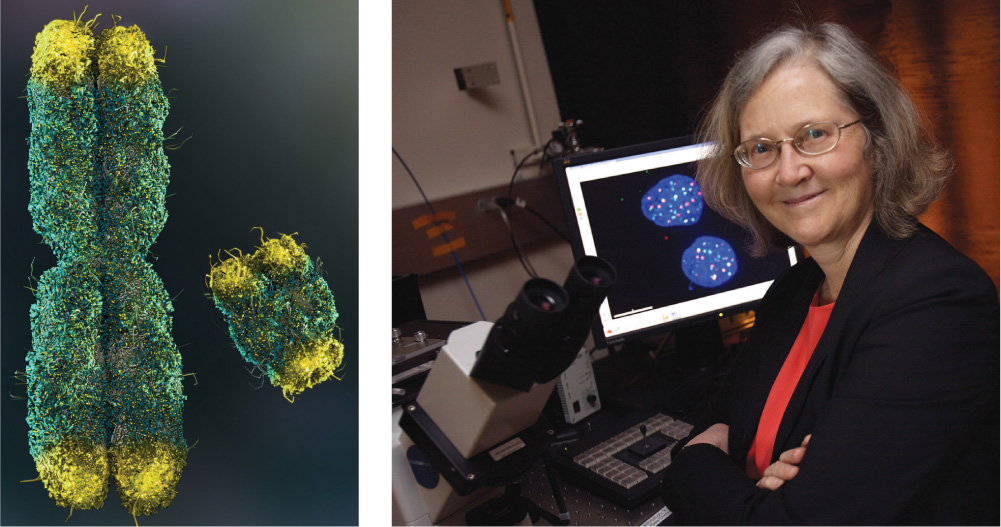

THOR SWIFT/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX PICTURES

Understanding this process requires knowing a little bit about how aging occurs. The cells in our bodies are constantly dividing, and as part of this process, our chromosomes are repeatedly copied so that our genetic information is carried into the new cells. This process is facilitated by the presence of telomeres, caps at the ends of each chromosome that protect the ends of chromosomes and prevent them from sticking to each other. They are kind of like the tape at the end of your shoelaces that keeps them from being frayed and not working as efficiently. Each time a cell divides, the telomeres become slightly shorter. If they become too short, cells can no longer divide and this can lead to the development of tumors and a range of diseases. Fortunately, our bodies fix this problem by producing a substance called telomerase, an enzyme that rebuilds telomeres at the tips of chromosomes. As cells repeatedly divide over the course of our lives, telomerase does its best to re-

Interestingly, social stressors can play an important role in this process. People exposed to chronic stress have shorter telomere length and lower telomerase activity (Epel et al., 2004). Laboratory studies suggest that cortisol can reduce the activity of telomerase, which in turn leads to shortened telomeres, which has downstream negative effects in the form of accelerated aging and increased risk of a wide range of diseases including cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and depression (Blackburn & Epel, 2012). This sounds dire, but there are things that you can do to combat this process and potentially live a healthier and longer life! Activities like exercise and meditation seem to prevent chronic stress from shortening telomere length, providing a potential explanation of how these activities may convey health benefits such as longer life and lower risk of disease (Epel et al., 2009; Puterman et al., 2010).

557

Stress Effects on the Immune Response

How does stress affect the immune system?

The immune system is a complex response system that protects the body from bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances. The system includes white blood cells, such as lymphocytes (including T cells and B cells), that produce antibodies that fight infection. The immune system is remarkably responsive to psychological influences. Psychoneuro-

For example, in one study, medical student volunteers agreed to receive small wounds to the roof of the mouth. Researchers observed that these wounds healed more slowly during exam periods than during summer vacation (Marucha, Kiecolt-

The effect of stress on immune response may help to explain why social status is related to health. Studies of British civil servants beginning in the 1960s found that mortality varied precisely with civil service grade: the higher the classification, the lower the death rate, regardless of cause (Marmot et al., 1991). One explanation is that people in lower-

Stress and cardiovascular Health

The heart and circulatory system are also sensitive to stress. For example, for several days after Iraq’s 1991 missile attack on Israel, heart attack rates went up markedly among citizens in Tel Aviv (Meisel et al., 1991). The full story of how stress affects the cardiovascular system starts earlier than the occurrence of a heart attack: Chronic stress creates changes in the body that increase later vulnerability.

558

The main cause of coronary heart disease is atherosclerosis, a gradual narrowing of the arteries that occurs as fatty deposits, or plaque, build up on the inner walls of the arteries. Narrowed arteries result in a reduced blood supply and, eventually, when an artery is blocked by a blood clot or detached plaque, in a heart attack. Although smoking, a sedentary lifestyle, and a diet high in fat and cholesterol can cause coronary heart disease, chronic stress also is a major contributor (Krantz & McCeney, 2002). As a result of stress-

How does chronic stress increase the chance of a heart attack?

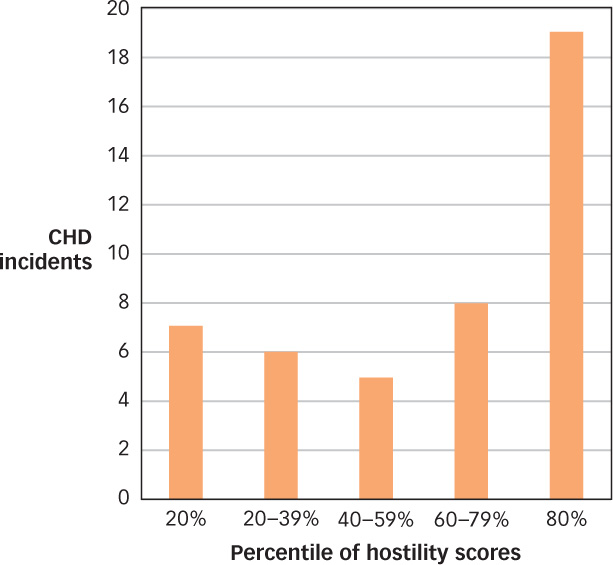

Figure 14.3: Hostility and Coronary Heart Disease Of 2,280 men studied over the course of 3 years, 45 suffered coronary heart disease (CHD) incidents, such as heart attack. Many more of these incidents occurred in the group who had initially scored above the 80th percentile in hostility (Niaura et al., 2002).

Figure 14.3: Hostility and Coronary Heart Disease Of 2,280 men studied over the course of 3 years, 45 suffered coronary heart disease (CHD) incidents, such as heart attack. Many more of these incidents occurred in the group who had initially scored above the 80th percentile in hostility (Niaura et al., 2002).

In the 1950s, cardiologists Meyer Friedman and Ray Rosenman (1974) conducted a revolutionary study that demonstrated a link between work-

What causal factor most predicts heart attacks?

A later study of stress and anger tracked medical students for up to 48 years to see how their behavior while they were young related to their later susceptibility to coronary problems (Chang et al., 2002). Students who responded to stress with anger and hostility were found to be 3 times more likely later to develop premature heart disease and 6 times more likely to have an early heart attack than were students who did not respond with anger. Hostility, particularly in men, predicts heart disease better than any other major causal factor, such as smoking, high caloric intake, or even high levels of LDL cholesterol (Niaura et al., 2002; see also FIGURE 14.3). Stress affects the cardiovascular system to some degree in everyone, but is particularly harmful in those people who respond to stressful events with hostility.

Psychological Reactions

The body’s response to stress is intertwined with responses of the mind. Perhaps the first thing the mind does is try to sort things out—

559

Stress Interpretation

The interpretation of a stimulus as stressful or not is called primary appraisal (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Primary appraisal allows you to realize that a small dark spot on your shirt is a stressor (spider!) or that a 70-

What is the difference between a threat and a challenge?

The next step in interpretation is secondary appraisal, determining whether the stressor is something you can handle or not; that is, whether you have control over the event (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Interestingly, the body responds differently depending on whether the stressor is perceived as a threat (a stressor you believe you might not be able to overcome) or a challenge (a stressor you feel fairly confident you can control; Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996). The same midterm exam is seen as a challenge if you are well prepared, but a threat if you didn’t study. Fortunately, interpretations of stressors can change them from threats to challenges. One recent study (Jamieson et al., 2010) showed that instructing students to reframe their anxiety about an upcoming exam as arousal that will help them on the test actually boosted their sympathetic arousal (signaling a challenge orientation) and improved test performance. Remember this technique next time you are feeling anxious about a test: Increased arousal can improve your performance!

Although both threats and challenges raise heart rate, threats increase vascular reactivity (such as constriction of the blood vessels, which can lead to high blood pressure; see the Hot Science box). In one study, researchers found that even interactions as innocuous as conversations can produce threat or challenge responses depending on the race of the conversation partner. Asked to talk with another, unfamiliar student, White students showed a challenge reaction when the student was White and a threat reaction when the student was African American (Mendes et al., 2002). Similar threat responses were found when White students interacted with an unexpected partner, such as an Asian student with a Southern U.S. accent (Mendes et al., 2007). It’s as if social unfamiliarity creates the same kind of stress as lack of preparedness for an exam. Interestingly, having previously interacted with members of an unfamiliar group tempers the threat reaction (Blascovich et al., 2001).

Burnout

Did you ever take a class from an instructor who had lost interest in the job? The syndrome is easy to spot: The teacher looks distant and blank, almost robotic, giving predictable and humdrum lessons each day, as if it doesn’t matter whether anyone is listening. Now imagine being this instructor. You decided to teach because you wanted to shape young minds. You worked hard, and for a while things were great. But one day, you looked up to see a room full of miserable students who were bored and didn’t care about anything you had to say. They updated their Facebook pages while you talked and started shuffling papers and putting things away long before the end of class. You’re happy at work only when you’re not in class. When people feel this way, especially about their jobs or careers, they are suffering from burnout, a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion created by long-

560

Why is burnout a problem especially in the helping professions?

Burnout is a particular problem in the helping professions (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). Teachers, nurses, clergy, doctors, dentists, psychologists, social workers, police officers, and others who repeatedly encounter emotional turmoil on the job may only be able to work productively for a limited time. Eventually, many succumb to symptoms of burnout: overwhelming exhaustion, a deep cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment (Maslach, 2003). Their unhappiness can even spread to others; people with burnout tend to become disgruntled employees who revel in their coworkers’ failures and ignore their coworkers’ successes (Brenninkmeijer, Vanyperen, & Buunk, 2001).

What causes burnout? One theory suggests that the culprit is using your job to give meaning to your life (Pines, 1993). If you define yourself only by your career and gauge your self-

The body responds to stress with an initial fight-

The body responds to stress with an initial fight-or- flight reaction, which activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical (HPA) axis and prepares the body to face the threat or run away from it.  The general adaptation syndrome (GAS) outlines three phases of stress response that occur regardless of the type of stressor: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion.

The general adaptation syndrome (GAS) outlines three phases of stress response that occur regardless of the type of stressor: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion. Chronic stress can wear down the immune system, causing susceptibility to infection, aging, tumor growth, organ damage, and death.

Chronic stress can wear down the immune system, causing susceptibility to infection, aging, tumor growth, organ damage, and death. Response to stress varies if it’s interpreted as something that can be overcome or not.

Response to stress varies if it’s interpreted as something that can be overcome or not. The psychological response to stress can, if prolonged, lead to burnout.

The psychological response to stress can, if prolonged, lead to burnout.

561